Assignment statements in Python do not create copies of objects, they only bind names to an object. For immutable objects, that usually doesn’t make a difference.

But for working with mutable objects or collections of mutable objects, you might be looking for a way to create “real copies” or “clones” of these objects.

Essentially, you’ll sometimes want copies that you can modify without automatically modifying the original at the same time. In this article I’m going to give you the rundown on how to copy or “clone” objects in Python 3 and some of the caveats involved.

Note: This tutorial was written with Python 3 in mind but there is little difference between Python 2 and 3 when it comes to copying objects. When there are differences I will point them out in the text.

Let’s start by looking at how to copy Python’s built-in collections. Python’s built-in mutable collections like lists, dicts, and sets can be copied by calling their factory functions on an existing collection:

new_list = list(original_list)

new_dict = dict(original_dict)

new_set = set(original_set)

However, this method won’t work for custom objects and, on top of that, it only creates shallow copies. For compound objects like lists, dicts, and sets, there’s an important difference between shallow and deep copying:

-

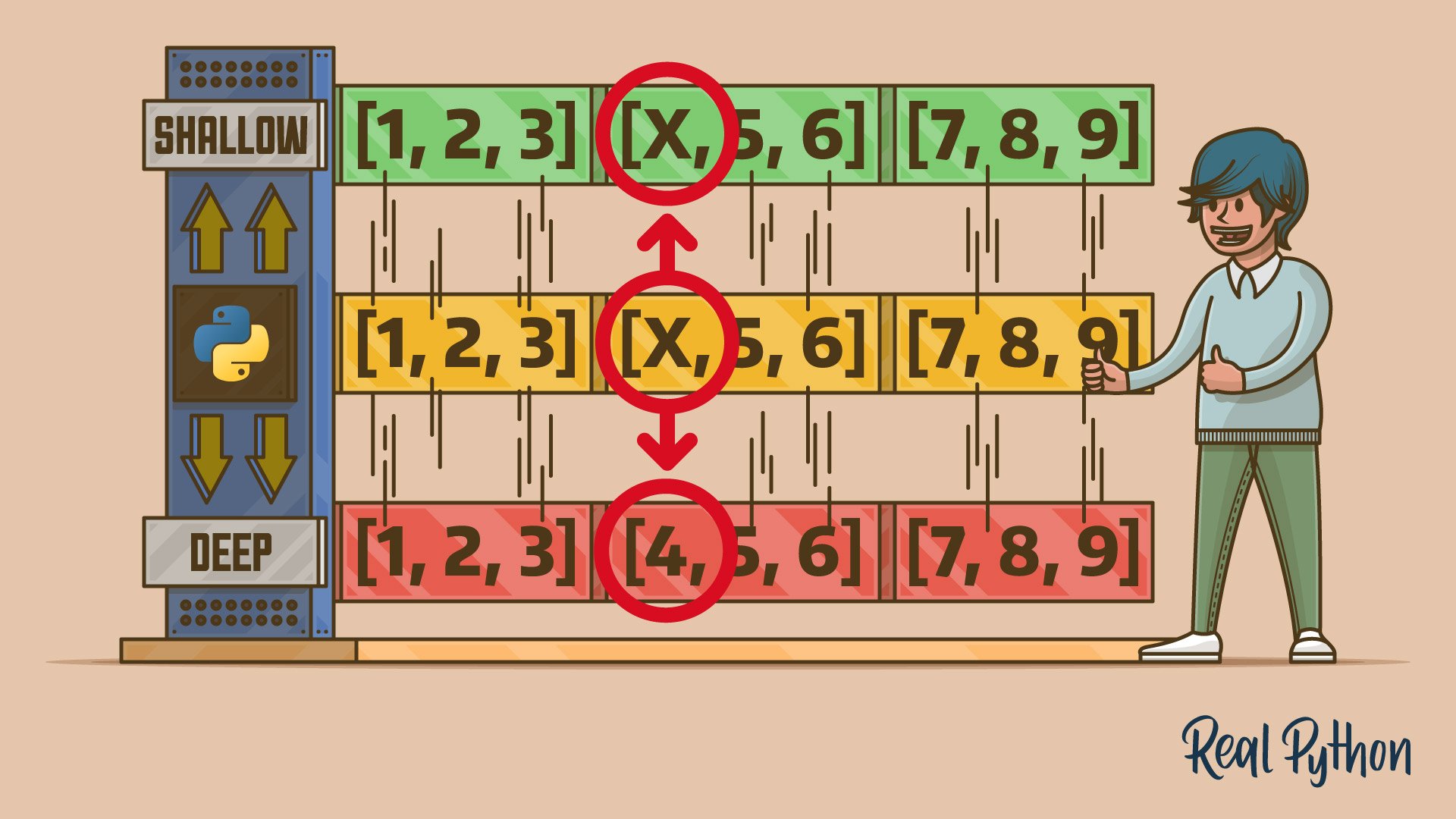

A shallow copy means constructing a new collection object and then populating it with references to the child objects found in the original. In essence, a shallow copy is only one level deep. The copying process does not recurse and therefore won’t create copies of the child objects themselves.

-

A deep copy makes the copying process recursive. It means first constructing a new collection object and then recursively populating it with copies of the child objects found in the original. Copying an object this way walks the whole object tree to create a fully independent clone of the original object and all of its children.

I know, that was a bit of a mouthful. So let’s look at some examples to drive home this difference between deep and shallow copies.

Free Download: Get a sample chapter from Python Tricks: The Book that shows you Python’s best practices with simple examples you can apply instantly to write more beautiful + Pythonic code.

Making Shallow Copies

In the example below, we’ll create a new nested list and then shallowly copy it with the list() factory function:

>>> xs = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

>>> ys = list(xs) # Make a shallow copy

This means ys will now be a new and independent object with the same contents as xs. You can verify this by inspecting both objects:

>>> xs

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

>>> ys

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

To confirm ys really is independent from the original, let’s devise a little experiment. You could try and add a new sublist to the original (xs) and then check to make sure this modification didn’t affect the copy (ys):

>>> xs.append(['new sublist'])

>>> xs

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9], ['new sublist']]

>>> ys

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

As you can see, this had the expected effect. Modifying the copied list at a “superficial” level was no problem at all.

However, because we only created a shallow copy of the original list, ys still contains references to the original child objects stored in xs.

These children were not copied. They were merely referenced again in the copied list.

Therefore, when you modify one of the child objects in xs, this modification will be reflected in ys as well—that’s because both lists share the same child objects. The copy is only a shallow, one level deep copy:

>>> xs[1][0] = 'X'

>>> xs

[[1, 2, 3], ['X', 5, 6], [7, 8, 9], ['new sublist']]

>>> ys

[[1, 2, 3], ['X', 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

In the above example we (seemingly) only made a change to xs. But it turns out that both sublists at index 1 in xs and ys were modified. Again, this happened because we had only created a shallow copy of the original list.

Had we created a deep copy of xs in the first step, both objects would’ve been fully independent. This is the practical difference between shallow and deep copies of objects.

Now you know how to create shallow copies of some of the built-in collection classes, and you know the difference between shallow and deep copying. The questions we still want answers for are:

- How can you create deep copies of built-in collections?

- How can you create copies (shallow and deep) of arbitrary objects, including custom classes?

The answer to these questions lies in the copy module in the Python standard library. This module provides a simple interface for creating shallow and deep copies of arbitrary Python objects.

Making Deep Copies

Let’s repeat the previous list-copying example, but with one important difference. This time we’re going to create a deep copy using the deepcopy() function defined in the copy module instead:

>>> import copy

>>> xs = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

>>> zs = copy.deepcopy(xs)

When you inspect xs and its clone zs that we created with copy.deepcopy(), you’ll see that they both look identical again—just like in the previous example:

>>> xs

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

>>> zs

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

However, if you make a modification to one of the child objects in the original object (xs), you’ll see that this modification won’t affect the deep copy (zs).

Both objects, the original and the copy, are fully independent this time. xs was cloned recursively, including all of its child objects:

>>> xs[1][0] = 'X'

>>> xs

[[1, 2, 3], ['X', 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

>>> zs

[[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

You might want to take some time to sit down with the Python interpreter and play through these examples right about now. Wrapping your head around copying objects is easier when you get to experience and play with the examples firsthand.

By the way, you can also create shallow copies using a function in the copy module. The copy.copy() function creates shallow copies of objects.

This is useful if you need to clearly communicate that you’re creating a shallow copy somewhere in your code. Using copy.copy() lets you indicate this fact. However, for built-in collections it’s considered more Pythonic to simply use the list, dict, and set factory functions to create shallow copies.

Copying Arbitrary Python Objects

The question we still need to answer is how do we create copies (shallow and deep) of arbitrary objects, including custom classes. Let’s take a look at that now.

Again the copy module comes to our rescue. Its copy.copy() and copy.deepcopy() functions can be used to duplicate any object.

Once again, the best way to understand how to use these is with a simple experiment. I’m going to base this on the previous list-copying example. Let’s start by defining a simple 2D point class:

class Point:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def __repr__(self):

return f'Point({self.x!r}, {self.y!r})'

I hope you agree that this was pretty straightforward. I added a __repr__() implementation so that we can easily inspect objects created from this class in the Python interpreter.

Note: The above example uses a Python 3.6 f-string to construct the string returned by

__repr__. On Python 2 and versions of Python 3 before 3.6 you’d use a different string formatting expression, for example:PythonCopied!def __repr__(self): return 'Point(%r, %r)' % (self.x, self.y)

Next up, we’ll create a Point instance and then (shallowly) copy it, using the copy module:

>>> a = Point(23, 42)

>>> b = copy.copy(a)

If we inspect the contents of the original Point object and its (shallow) clone, we see what we’d expect:

>>> a

Point(23, 42)

>>> b

Point(23, 42)

>>> a is b

False

Here’s something else to keep in mind. Because our point object uses immutable types (ints) for its coordinates, there’s no difference between a shallow and a deep copy in this case. But I’ll expand the example in a second.

Let’s move on to a more complex example. I’m going to define another class to represent 2D rectangles. I’ll do it in a way that allows us to create a more complex object hierarchy—my rectangles will use Point objects to represent their coordinates:

class Rectangle:

def __init__(self, topleft, bottomright):

self.topleft = topleft

self.bottomright = bottomright

def __repr__(self):

return (f'Rectangle({self.topleft!r}, '

f'{self.bottomright!r})')

Again, first we’re going to attempt to create a shallow copy of a rectangle instance:

rect = Rectangle(Point(0, 1), Point(5, 6))

srect = copy.copy(rect)

If you inspect the original rectangle and its copy, you’ll see how nicely the __repr__() override is working out, and that the shallow copy process worked as expected:

>>> rect

Rectangle(Point(0, 1), Point(5, 6))

>>> srect

Rectangle(Point(0, 1), Point(5, 6))

>>> rect is srect

False

Remember how the previous list example illustrated the difference between deep and shallow copies? I’m going to use the same approach here. I’ll modify an object deeper in the object hierarchy, and then you’ll see this change reflected in the (shallow) copy as well:

>>> rect.topleft.x = 999

>>> rect

Rectangle(Point(999, 1), Point(5, 6))

>>> srect

Rectangle(Point(999, 1), Point(5, 6))

I hope this behaved how you expected it to. Next, I’ll create a deep copy of the original rectangle. Then I’ll apply another modification and you’ll see which objects are affected:

>>> drect = copy.deepcopy(srect)

>>> drect.topleft.x = 222

>>> drect

Rectangle(Point(222, 1), Point(5, 6))

>>> rect

Rectangle(Point(999, 1), Point(5, 6))

>>> srect

Rectangle(Point(999, 1), Point(5, 6))

Voila! This time the deep copy (drect) is fully independent of the original (rect) and the shallow copy (srect).

We’ve covered a lot of ground here, and there are still some finer points to copying objects.

It pays to go deep (ha!) on this topic, so you may want to study up on the copy module documentation. For example, objects can control how they’re copied by defining the special methods __copy__() and __deepcopy__() on them.

3 Things to Remember

- Making a shallow copy of an object won’t clone child objects. Therefore, the copy is not fully independent of the original.

- A deep copy of an object will recursively clone child objects. The clone is fully independent of the original, but creating a deep copy is slower.

- You can copy arbitrary objects (including custom classes) with the

copymodule.

If you’d like to dig deeper into other intermediate-level Python programming techniques, check out this free bonus:

Free Download: Get a sample chapter from Python Tricks: The Book that shows you Python’s best practices with simple examples you can apply instantly to write more beautiful + Pythonic code.