Ever wonder how Python handles your data behind the scenes? How are your variables stored in memory? When do they get deleted?

In this article, we’re going to do a deep dive into the internals of Python to understand how it handles memory management.

By the end of this article, you’ll:

- Learn more about low-level computing, specifically as relates to memory

- Understand how Python abstracts lower-level operations

- Learn about Python’s internal memory management algorithms

Understanding Python’s internals will also give you better insight into some of Python’s behaviors. Hopefully, you’ll gain a new appreciation for Python as well. So much logic is happening behind the scenes to ensure your program works the way you expect.

Free Bonus: 5 Thoughts On Python Mastery, a free course for Python developers that shows you the roadmap and the mindset you’ll need to take your Python skills to the next level.

Memory Is an Empty Book

You can begin by thinking of a computer’s memory as an empty book intended for short stories. There’s nothing written on the pages yet. Eventually, different authors will come along. Each author wants some space to write their story in.

Since they aren’t allowed to write over each other, they must be careful about which pages they write in. Before they begin writing, they consult the manager of the book. The manager then decides where in the book they’re allowed to write.

Since this book is around for a long time, many of the stories in it are no longer relevant. When no one reads or references the stories, they are removed to make room for new stories.

In essence, computer memory is like that empty book. In fact, it’s common to call fixed-length contiguous blocks of memory pages, so this analogy holds pretty well.

The authors are like different applications or processes that need to store data in memory. The manager, who decides where the authors can write in the book, plays the role of a memory manager of sorts. The person who removed the old stories to make room for new ones is a garbage collector.

Memory Management: From Hardware to Software

Memory management is the process by which applications read and write data. A memory manager determines where to put an application’s data. Since there’s a finite chunk of memory, like the pages in our book analogy, the manager has to find some free space and provide it to the application. This process of providing memory is generally called memory allocation.

On the flip side, when data is no longer needed, it can be deleted, or freed. But freed to where? Where did this “memory” come from?

Somewhere in your computer, there’s a physical device storing data when you’re running your Python programs. There are many layers of abstraction that the Python code goes through before the objects actually get to the hardware though.

One of the main layers above the hardware (such as RAM or a hard drive) is the operating system (OS). It carries out (or denies) requests to read and write memory.

Above the OS, there are applications, one of which is the default Python implementation (included in your OS or downloaded from python.org.) Memory management for your Python code is handled by the Python application. The algorithms and structures that the Python application uses for memory management is the focus of this article.

The Default Python Implementation

The default Python implementation, CPython, is actually written in the C programming language.

When I first heard this, it blew my mind. A language that’s written in another language?! Well, not really, but sort of.

The Python language is defined in a reference manual written in English. However, that manual isn’t all that useful by itself. You still need something to interpret written code based on the rules in the manual.

You also need something to actually execute interpreted code on a computer. The default Python implementation fulfills both of those requirements. It converts your Python code into instructions that it then runs on a virtual machine.

Note: Virtual machines are like physical computers, but they are implemented in software. They typically process basic instructions similar to Assembly instructions.

Python is an interpreted programming language. Your Python code actually gets compiled down to more computer-readable instructions called bytecode. These instructions get interpreted by a virtual machine when you run your code.

Have you ever seen a .pyc file or a __pycache__ folder? That’s the bytecode that gets interpreted by the virtual machine.

It’s important to note that there are implementations other than CPython. IronPython compiles down to run on Microsoft’s Common Language Runtime. Jython compiles down to Java bytecode to run on the Java Virtual Machine. Then there’s PyPy, but that deserves its own entire article, so I’ll just mention it in passing.

For the purposes of this article, I’ll focus on the memory management done by the default implementation of Python, CPython.

Disclaimer: While a lot of this information will carry through to new versions of Python, things may change in the future. Note that the referenced version for this article is the current latest version of Python, 3.7.

Okay, so CPython is written in C, and it interprets Python bytecode. What does this have to do with memory management? Well, the memory management algorithms and structures exist in the CPython code, in C. To understand the memory management of Python, you have to get a basic understanding of CPython itself.

CPython is written in C, which does not natively support object-oriented programming. Because of that, there are quite a bit of interesting designs in the CPython code.

You may have heard that everything in Python is an object, even types such as int and str. Well, it’s true on an implementation level in CPython. There is a struct called a PyObject, which every other object in CPython uses.

Note: A struct, or structure, in C is a custom data type that groups together different data types. To compare to object-oriented languages, it’s like a class with attributes and no methods.

The PyObject, the grand-daddy of all objects in Python, contains only two things:

ob_refcnt: reference countob_type: pointer to another type

The reference count is used for garbage collection. Then you have a pointer to the actual object type. That object type is just another struct that describes a Python object (such as a dict or int).

Each object has its own object-specific memory allocator that knows how to get the memory to store that object. Each object also has an object-specific memory deallocator that “frees” the memory once it’s no longer needed.

However, there’s an important factor in all this talk about allocating and freeing memory. Memory is a shared resource on the computer, and bad things can happen if two different processes try to write to the same location at the same time.

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

The GIL is a solution to the common problem of dealing with shared resources, like memory in a computer. When two threads try to modify the same resource at the same time, they can step on each other’s toes. The end result can be a garbled mess where neither of the threads ends up with what they wanted.

Consider the book analogy again. Suppose that two authors stubbornly decide that it’s their turn to write. Not only that, but they both need to write on the same page of the book at the same time.

They each ignore the other’s attempt to craft a story and begin writing on the page. The end result is two stories on top of each other, which makes the whole page completely unreadable.

One solution to this problem is a single, global lock on the interpreter when a thread is interacting with the shared resource (the page in the book). In other words, only one author can write at a time.

Python’s GIL accomplishes this by locking the entire interpreter, meaning that it’s not possible for another thread to step on the current one. When CPython handles memory, it uses the GIL to ensure that it does so safely.

There are pros and cons to this approach, and the GIL is heavily debated in the Python community. To read more about the GIL, I suggest checking out What is the Python Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)?.

Garbage Collection

Let’s revisit the book analogy and assume that some of the stories in the book are getting very old. No one is reading or referencing those stories anymore. If no one is reading something or referencing it in their own work, you could get rid of it to make room for new writing.

That old, unreferenced writing could be compared to an object in Python whose reference count has dropped to 0. Remember that every object in Python has a reference count and a pointer to a type.

The reference count gets increased for a few different reasons. For example, the reference count will increase if you assign it to another variable:

numbers = [1, 2, 3]

# Reference count = 1

more_numbers = numbers

# Reference count = 2

It will also increase if you pass the object as an argument:

total = sum(numbers)

As a final example, the reference count will increase if you include the object in a list:

matrix = [numbers, numbers, numbers]

Python allows you to inspect the current reference count of an object with the sys module. You can use sys.getrefcount(numbers), but keep in mind that passing in the object to getrefcount() increases the reference count by 1.

In any case, if the object is still required to hang around in your code, its reference count is greater than 0. Once it drops to 0, the object has a specific deallocation function that is called which “frees” the memory so that other objects can use it.

But what does it mean to “free” the memory, and how do other objects use it? Let’s jump right into CPython’s memory management.

CPython’s Memory Management

We’re going to dive deep into CPython’s memory architecture and algorithms, so buckle up.

As mentioned before, there are layers of abstraction from the physical hardware to CPython. The operating system (OS) abstracts the physical memory and creates a virtual memory layer that applications (including Python) can access.

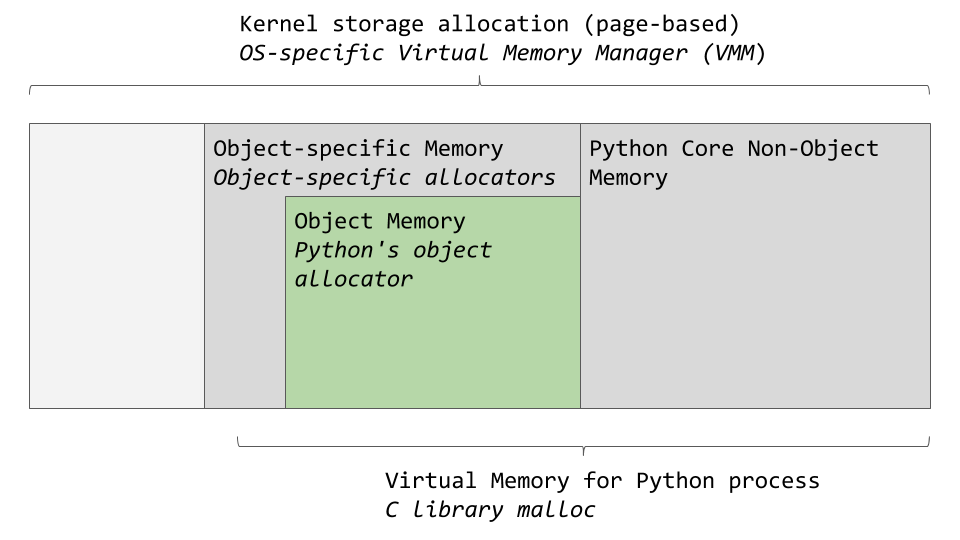

An OS-specific virtual memory manager carves out a chunk of memory for the Python process. The darker gray boxes in the image below are now owned by the Python process.

Python uses a portion of the memory for internal use and non-object memory. The other portion is dedicated to object storage (your int, dict, and the like). Note that this was somewhat simplified. If you want the full picture, you can check out the CPython source code, where all this memory management happens.

CPython has an object allocator that is responsible for allocating memory within the object memory area. This object allocator is where most of the magic happens. It gets called every time a new object needs space allocated or deleted.

Typically, the adding and removing of data for Python objects like list and int doesn’t involve too much data at a time. So the design of the allocator is tuned to work well with small amounts of data at a time. It also tries not to allocate memory until it’s absolutely required.

The comments in the source code describe the allocator as “a fast, special-purpose memory allocator for small blocks, to be used on top of a general-purpose malloc.” In this case, malloc is C’s library function for memory allocation.

Now we’ll look at CPython’s memory allocation strategy. First, we’ll talk about the 3 main pieces and how they relate to each other.

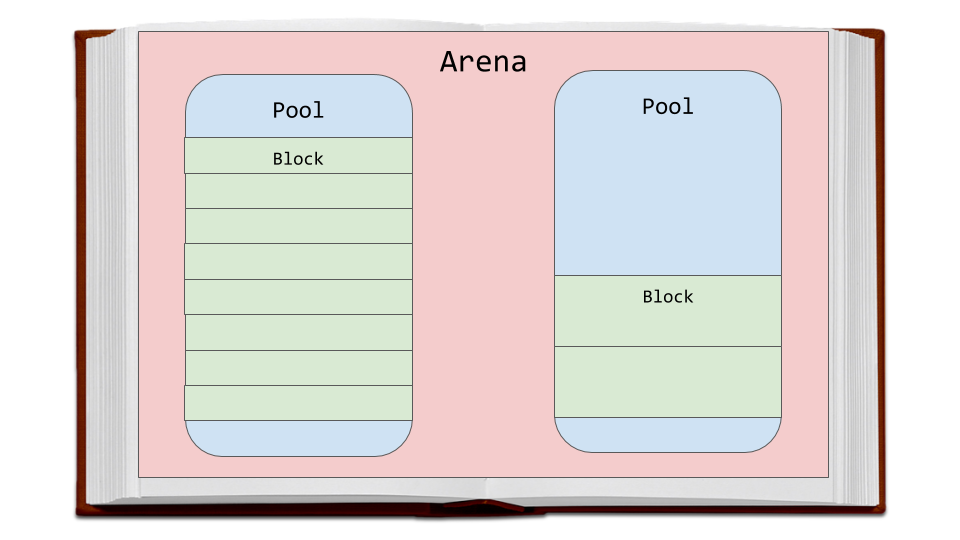

Arenas are the largest chunks of memory and are aligned on a page boundary in memory. A page boundary is the edge of a fixed-length contiguous chunk of memory that the OS uses. Python assumes the system’s page size is 256 kilobytes.

Within the arenas are pools, which are one virtual memory page (4 kilobytes). These are like the pages in our book analogy. These pools are fragmented into smaller blocks of memory.

All the blocks in a given pool are of the same “size class.” A size class defines a specific block size, given some amount of requested data. The chart below is taken directly from the source code comments:

| Request in bytes | Size of allocated block | Size class idx |

|---|---|---|

| 1-8 | 8 | 0 |

| 9-16 | 16 | 1 |

| 17-24 | 24 | 2 |

| 25-32 | 32 | 3 |

| 33-40 | 40 | 4 |

| 41-48 | 48 | 5 |

| 49-56 | 56 | 6 |

| 57-64 | 64 | 7 |

| 65-72 | 72 | 8 |

| … | … | … |

| 497-504 | 504 | 62 |

| 505-512 | 512 | 63 |

For example, if 42 bytes are requested, the data would be placed into a size 48-byte block.

Pools

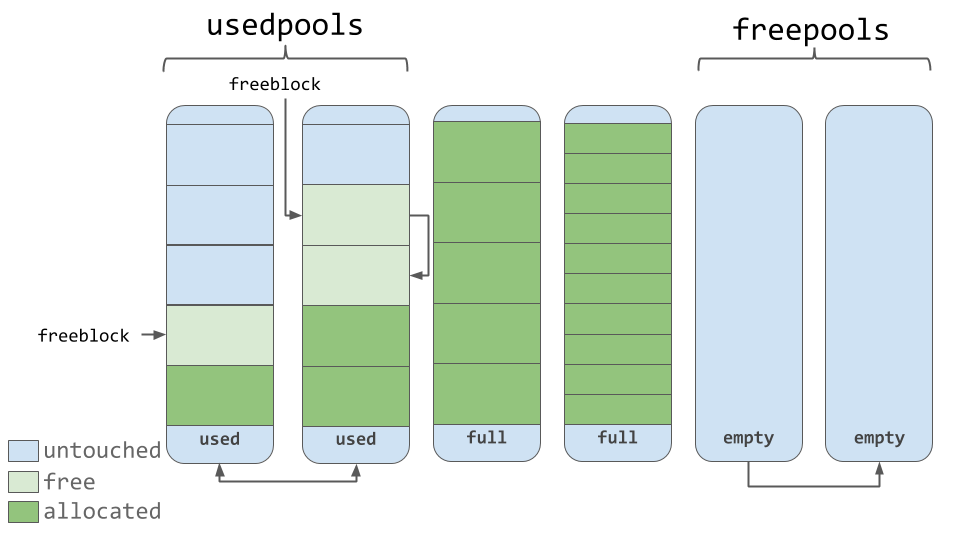

Pools are composed of blocks from a single size class. Each pool maintains a double-linked list to other pools of the same size class. In that way, the algorithm can easily find available space for a given block size, even across different pools.

A usedpools list tracks all the pools that have some space available for data for each size class. When a given block size is requested, the algorithm checks this usedpools list for the list of pools for that block size.

Pools themselves must be in one of 3 states: used, full, or empty. A used pool has available blocks for data to be stored. A full pool’s blocks are all allocated and contain data. An empty pool has no data stored and can be assigned any size class for blocks when needed.

A freepools list keeps track of all the pools in the empty state. But when do empty pools get used?

Assume your code needs an 8-byte chunk of memory. If there are no pools in usedpools of the 8-byte size class, a fresh empty pool is initialized to store 8-byte blocks. This new pool then gets added to the usedpools list so it can be used for future requests.

Say a full pool frees some of its blocks because the memory is no longer needed. That pool would get added back to the usedpools list for its size class.

You can see now how pools can move between these states (and even memory size classes) freely with this algorithm.

Blocks

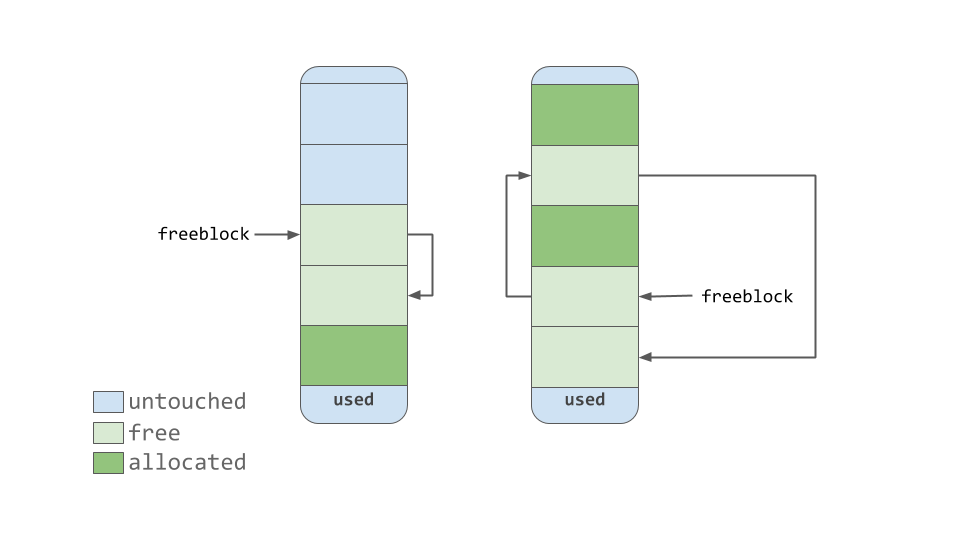

As seen in the diagram above, pools contain a pointer to their “free” blocks of memory. There’s a slight nuance to the way this works. This allocator “strives at all levels (arena, pool, and block) never to touch a piece of memory until it’s actually needed,” according to the comments in the source code.

That means that a pool can have blocks in 3 states. These states can be defined as follows:

untouched: a portion of memory that has not been allocatedfree: a portion of memory that was allocated but later made “free” by CPython and that no longer contains relevant dataallocated: a portion of memory that actually contains relevant data

The freeblock pointer points to a singly linked list of free blocks of memory. In other words, a list of available places to put data. If more than the available free blocks are needed, the allocator will get some untouched blocks in the pool.

As the memory manager makes blocks “free,” those now free blocks get added to the front of the freeblock list. The actual list may not be contiguous blocks of memory, like the first nice diagram. It may look something like the diagram below:

Arenas

Arenas contain pools. Those pools can be used, full, or empty. Arenas themselves don’t have as explicit states as pools do though.

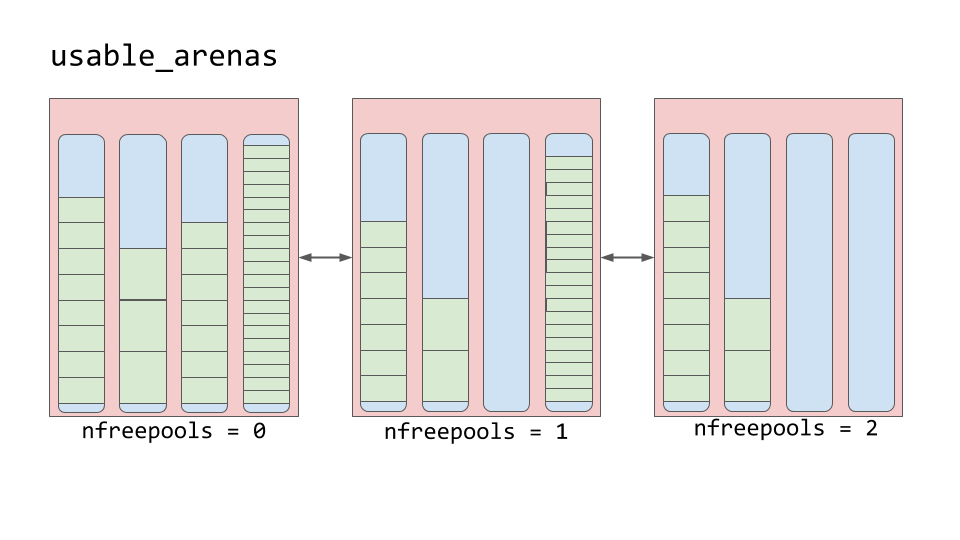

Arenas are instead organized into a doubly linked list called usable_arenas. The list is sorted by the number of free pools available. The fewer free pools, the closer the arena is to the front of the list.

This means that the arena that is the most full of data will be selected to place new data into. But why not the opposite? Why not place data where there’s the most available space?

This brings us to the idea of truly freeing memory. You’ll notice that I’ve been saying “free” in quotes quite a bit. The reason is that when a block is deemed “free”, that memory is not actually freed back to the operating system. The Python process keeps it allocated and will use it later for new data. Truly freeing memory returns it to the operating system to use.

Arenas are the only things that can truly be freed. So, it stands to reason that those arenas that are closer to being empty should be allowed to become empty. That way, that chunk of memory can be truly freed, reducing the overall memory footprint of your Python program.

Conclusion

Memory management is an integral part of working with computers. Python handles nearly all of it behind the scenes, for better or for worse.

In this article, you learned:

- What memory management is and why it’s important

- How the default Python implementation, CPython, is written in the C programming language

- How the data structures and algorithms work together in CPython’s memory management to handle your data

Python abstracts away a lot of the gritty details of working with computers. This gives you the power to work on a higher level to develop your code without the headache of worrying about how and where all those bytes are getting stored.