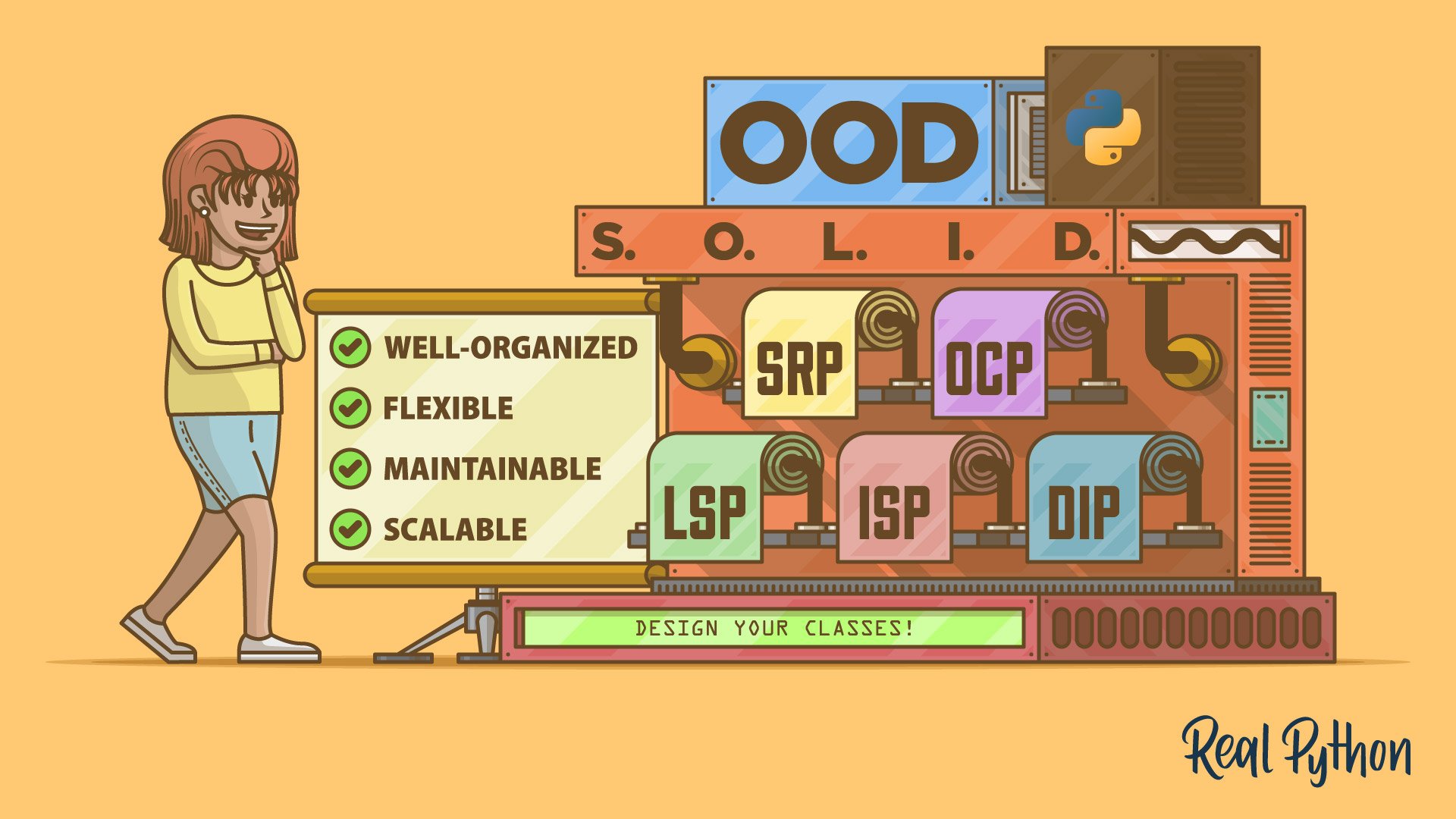

A great approach to writing high-quality object-oriented Python code is to consistently apply the SOLID design principles. SOLID is a set of five object-oriented design principles that can help you write maintainable, flexible, and scalable code based on well-designed, cleanly structured classes. These principles are foundational best practices in object-oriented design.

In this tutorial, you’ll explore each of these principles with concrete examples and refactor your code so that it adheres to the principle at hand.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand that:

- You apply the SOLID design principles to write classes that you can confidently maintain, extend, test, and reason about.

- You can apply SOLID principles to split responsibilities, extend via abstractions, honor subtype contracts, keep interfaces small, and invert dependencies.

- You enforce the Single-Responsibility Principle by separating tasks into specialized classes, giving each class only one reason to change.

- You satisfy the Open-Closed Principle by defining an abstract class with the required interface and adding new subclasses without modifying existing code.

- You honor the Liskov Substitution Principle by making the subtypes preserve their expected behaviors.

- You implement Dependency Inversion by making your classes depend on abstractions rather than on details.

Follow the examples to refactor each design, verify behaviors, and internalize how each SOLID design principle can improve your code.

Free Bonus: Click here to download sample code so you can build clean, maintainable classes with the SOLID Principles in Python.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “SOLID Design Principles: Improve Object-Oriented Code in Python” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

SOLID Design Principles: Improve Object-Oriented Code in PythonTest your Python understanding of Liskov substitution, Square–Rectangle pitfalls, and safer API design with polymorphism.

The SOLID Design Principles in Python

When it comes to writing classes and designing their interactions in Python, you can follow a series of principles that will help you build better object-oriented code. One of the most popular and widely accepted sets of standards for object-oriented design (OOD) is known as the SOLID design principles.

If you’re coming from C++ or Java, you may already be familiar with these principles. Maybe you’re wondering if the SOLID principles also apply to Python code. The answer to that question is a resounding yes. If you’re writing object-oriented code, then you should consider applying these principles to your OOD.

But what are these SOLID design principles? SOLID is an acronym that encompasses five core principles applicable to object-oriented design. These principles are the following:

- Single-responsibility principle (SRP)

- Open–closed principle (OCP)

- Liskov substitution principle (LSP)

- Interface segregation principle (ISP)

- Dependency inversion principle (DIP)

You’ll explore each of these principles in detail and code real-world examples of how to apply them in Python. In the process, you’ll gain a strong understanding of how to write more straightforward, organized, scalable, and reusable object-oriented code by applying the SOLID design principles. To kick things off, you’ll start with the first principle on the list.

Single-Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The single-responsibility principle (SRP) comes from Robert C. Martin, more commonly known by his nickname Uncle Bob. Martin is a well-respected figure in software engineering and one of the original signatories of the Agile Manifesto. He coined the term SOLID.

The single-responsibility principle states that:

A class should have only one reason to change.

This means that a class should have only one responsibility, as expressed through its methods. If a class takes care of more than one task, then you should separate those tasks into dedicated classes with descriptive names. Note that SRP isn’t only about responsibility but also about the reasons for changing the class implementation.

Note: You’ll find the SOLID design principles worded in various ways out there. In this tutorial, you’ll refer to them following the wording that Uncle Bob uses in his book Agile Software Development: Principles, Patterns, and Practices. So, all the direct quotes come from this book.

If you want to read alternate wordings in a quick roundup of these and related principles, then check out Uncle Bob’s The Principles of OOD.

This principle is closely related to the concept of separation of concerns, which suggests that you should divide your programs into components, each addressing a separate concern.

To illustrate the single-responsibility principle and how it can help you improve your object-oriented design, say that you have the following FileManager class:

file_manager_srp.py

from pathlib import Path

from zipfile import ZipFile

class FileManager:

def __init__(self, filename):

self.path = Path(filename)

def read(self, encoding="utf-8"):

return self.path.read_text(encoding)

def write(self, data, encoding="utf-8"):

self.path.write_text(data, encoding)

def compress(self):

with ZipFile(self.path.with_suffix(".zip"), mode="w") as archive:

archive.write(self.path)

def decompress(self):

with ZipFile(self.path.with_suffix(".zip"), mode="r") as archive:

archive.extractall()

In this example, your FileManager class has two different responsibilities. It manages files using the .read() and .write() methods. It also deals with ZIP archives by providing the .compress() and .decompress() methods.

This class violates the single-responsibility principle because there is more than one reason for changing its implementation (file I/O and ZIP handling). This implementation also makes code testing and code reuse harder.

To fix this issue and make your design more robust, you can split the class into two smaller, more focused classes, each with its own specific concern:

file_manager_srp.py

from pathlib import Path

from zipfile import ZipFile

class FileManager:

def __init__(self, filename):

self.path = Path(filename)

def read(self, encoding="utf-8"):

return self.path.read_text(encoding)

def write(self, data, encoding="utf-8"):

self.path.write_text(data, encoding)

class ZipFileManager:

def __init__(self, filename):

self.path = Path(filename)

def compress(self):

with ZipFile(self.path.with_suffix(".zip"), mode="w") as archive:

archive.write(self.path)

def decompress(self):

with ZipFile(self.path.with_suffix(".zip"), mode="r") as archive:

archive.extractall()

Now, you have two smaller classes, each having only a single responsibility:

FileManagertakes care of managing a file.ZipFileManagerhandles the compression and decompression of a file using the ZIP format.

These two classes are smaller, so they’re more manageable. They’re also easier to reason about, test, and debug.

The concept of responsibility in this context may be pretty subjective. Having a single responsibility doesn’t necessarily mean having a single method. Responsibility isn’t directly tied to the number of methods but to the core task that your class is responsible for, depending on your idea of what the class represents in your code. However, that subjectivity shouldn’t stop you from striving to use the SRP.

Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

The open-closed principle (OCP) for object-oriented design was originally introduced by Bertrand Meyer in 1988 and means that:

Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

To understand what the open-closed principle is all about, consider the following Shape class:

shapes_ocp.py

from math import pi

class Shape:

def __init__(self, shape_type, **kwargs):

self.shape_type = shape_type

if self.shape_type == "rectangle":

self.width = kwargs["width"]

self.height = kwargs["height"]

elif self.shape_type == "circle":

self.radius = kwargs["radius"]

else:

raise TypeError("Unsupported shape type")

def calculate_area(self):

if self.shape_type == "rectangle":

return self.width * self.height

elif self.shape_type == "circle":

return pi * self.radius**2

else:

raise TypeError("Unsupported shape type")

The initializer of Shape takes a shape_type argument that can be either "rectangle" or "circle". It also takes a specific set of keyword arguments using the **kwargs syntax. If you set the shape type to "rectangle", then you should also pass the width and height keyword arguments so that you can construct a proper rectangle.

In contrast, if you set the shape type to "circle", then you must also pass a radius argument to construct a circle. Finally, if you pass a different shape, like a "triangle", for example, then you’ll get an error because the class doesn’t support this shape.

Additionally, the class has a flaw: it doesn’t constrain the shape-type checking to a single place, the initialization. Instead, it requires checking all across the logic.

Note: This example may seem a bit extreme. Its intention is to clearly expose the core idea behind the open-closed principle.

Shape also has a .calculate_area() method that computes the area of the current shape according to its .shape_type attribute:

>>> from shapes_ocp import Shape

>>> rectangle = Shape("rectangle", width=10, height=5)

>>> rectangle.calculate_area()

50

>>> circle = Shape("circle", radius=5)

>>> circle.calculate_area()

78.53981633974483

The class works. You can create circles and rectangles, compute their area, and so on. However, imagine that you need to add a new shape, maybe a square. How would you do that? Well, the option here is to add another elif clause to .__init__() and to .calculate_area() so that you can address the requirements of a square shape.

Having to make these changes to create new shapes means that your class is open to modification, which violates the Open-Closed Principle.

Note: OCP doesn’t mean your classes should never be modified. It means that you should minimize the need to modify existing classes when adding new functionality to your code.

How can you fix your code to make it open to extension but closed to modification? Here’s a possible solution:

shapes_ocp.py

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from math import pi

class Shape(ABC):

def __init__(self, shape_type):

self.shape_type = shape_type

@abstractmethod

def calculate_area(self):

pass

class Circle(Shape):

def __init__(self, radius):

super().__init__("circle")

self.radius = radius

def calculate_area(self):

return pi * self.radius**2

class Rectangle(Shape):

def __init__(self, width, height):

super().__init__("rectangle")

self.width = width

self.height = height

def calculate_area(self):

return self.width * self.height

class Square(Shape):

def __init__(self, side):

super().__init__("square")

self.side = side

def calculate_area(self):

return self.side**2

In this code, you completely refactored the Shape class, turning it into an abstract base class (ABC). This class provides the required interface (API) for any shape that you’d like to define. That interface consists of a .shape_type attribute and a .calculate_area() method that you must override in all the subclasses.

Note: The example above and some examples in the next sections use Python’s ABCs to provide what’s called interface inheritance. In this type of inheritance, subclasses inherit interfaces rather than functionality. In contrast, when classes inherit functionality, then you’re presented with implementation inheritance.

This update makes the class closed for modification. Now, you can add new shapes to your class design without the need to modify Shape. In every case, you’ll have to implement the required interface, which also makes your classes polymorphic.

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Liskov substitution principle (LSP) was introduced by Barbara Liskov at an OOPSLA conference in 1987. Since then, this principle has been a fundamental part of object-oriented programming. The principle states that:

Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types.

For example, if you have a piece of code that works with a Shape class, then you should be able to substitute that class with any of its subclasses, such as Circle or Rectangle, without breaking the code.

Note: You can read the conference proceedings from the keynote where Barbara Liskov first shared this principle, or you can watch a short fragment of an interview with her for more context.

In practice, this principle is about making your subclasses behave like their base classes without breaking anyone’s expectations when they call the same methods.

To continue with shape-related examples, say you have a Rectangle class like the following:

shapes_lsp.py

class Rectangle:

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def calculate_area(self):

return self.width * self.height

In Rectangle, you’ve provided the .calculate_area() method, which operates with the .width and .height instance attributes.

Because a square is a special case of a rectangle with equal sides, you think of deriving a Square class from Rectangle in order to reuse the code. Then, you override the setter method for the .width and .height attributes so that when one side changes, the other side also changes:

shapes_lsp.py

# ...

class Square(Rectangle):

def __init__(self, side):

super().__init__(side, side)

def __setattr__(self, key, value):

super().__setattr__(key, value)

if key in ("width", "height"):

self.__dict__["width"] = value

self.__dict__["height"] = value

In this snippet of code, you’ve defined Square as a subclass of Rectangle. As a user might expect, the class constructor takes only the side of the square as an argument. Internally, the .__init__() method initializes the parent’s attributes, .width and .height, with the side argument.

You’ve also defined a special method, .__setattr__(), to hook into Python’s attribute-setting mechanism and intercept the assignment of a new value to either the .width or .height attribute. Specifically, when you set one of those attributes, the other attribute is also set to the same value:

>>> from shapes_lsp import Square

>>> square = Square(5)

>>> vars(square)

{'width': 5, 'height': 5}

>>> square.width = 7

>>> vars(square)

{'width': 7, 'height': 7}

>>> square.height = 9

>>> vars(square)

{'width': 9, 'height': 9}

Now, you’ve ensured that the Square object always remains a valid square, making your life easier for the small price of a bit of memory. Unfortunately, this violates the Liskov substitution principle because you can’t replace instances of Rectangle with their Square counterparts.

When someone expects a rectangle object in their code, they might assume that it’ll behave like one by exposing two independent .width and .height attributes. Meanwhile, your Square class breaks that assumption by changing the behavior promised by the object’s interface. That could have surprising and unwanted consequences, which would likely be hard to debug.

While a square is a specific type of rectangle in mathematics, the classes that represent those shapes shouldn’t inherit from each other via a parent-child relationship if you want them to abide by the LSP. One way to solve this problem is to create a base class for both Rectangle and Square to extend:

shapes_lsp.py

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Shape(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def calculate_area(self):

pass

class Rectangle(Shape):

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def calculate_area(self):

return self.width * self.height

class Square(Shape):

def __init__(self, side):

self.side = side

def calculate_area(self):

return self.side ** 2

Shape becomes the type that you can substitute through polymorphism with either Rectangle or Square, which are now siblings rather than a parent and a child. Notice that both concrete shape types have distinct sets of attributes and different initializer methods, and they could potentially implement other behaviors. The only thing that they have in common is the ability to calculate their area.

With this implementation in place, you can use the Shape type interchangeably with its Square and Rectangle subtypes when you only care about their common behavior:

>>> from shapes_lsp import Rectangle, Square

>>> def get_total_area(shapes):

... return sum(shape.calculate_area() for shape in shapes)

...

>>> get_total_area([Rectangle(10, 5), Square(5)])

75

Here, you pass a pair consisting of a rectangle and a square into a function that calculates their total area. Because the function only cares about the .calculate_area() method, it doesn’t matter that the shapes are different. This is the essence of the Liskov substitution principle.

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

The interface segregation principle (ISP) comes from the same mind as the single-responsibility principle. Yes, it’s another feather in Uncle Bob’s cap. The principle’s main idea is that:

Clients should not be forced to depend upon methods that they do not use. Interfaces belong to clients, not to hierarchies.

In this definition, clients are classes and subclasses, and interfaces consist of methods and attributes. In other words, if a class doesn’t use particular methods or attributes, then those methods and attributes should be segregated into more specific classes.

Consider the following example of a class hierarchy to model printing machines:

printers_isp.py

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Printer(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def print(self, document):

pass

@abstractmethod

def fax(self, document):

pass

@abstractmethod

def scan(self, document):

pass

class OldPrinter(Printer):

def print(self, document):

print(f"Printing {document} in black and white...")

def fax(self, document):

raise NotImplementedError("Fax functionality not supported")

def scan(self, document):

raise NotImplementedError("Scan functionality not supported")

class ModernPrinter(Printer):

def print(self, document):

print(f"Printing {document} in color...")

def fax(self, document):

print(f"Faxing {document}...")

def scan(self, document):

print(f"Scanning {document}...")

In this example, the base class, Printer, provides the interface that its subclasses must implement. OldPrinter inherits from Printer and must implement the same interface. However, OldPrinter doesn’t use the .fax() and .scan() methods because this type of printer doesn’t support these functionalities.

This implementation violates the ISP because it forces OldPrinter to expose an interface that the class doesn’t implement or need. To fix this issue, you should separate the interfaces into smaller and more specific classes. Then, you can create concrete classes by inheriting from multiple interface classes as needed:

printers_isp.py

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Printer(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def print(self, document):

pass

class Fax(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def fax(self, document):

pass

class Scanner(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def scan(self, document):

pass

class OldPrinter(Printer):

def print(self, document):

print(f"Printing {document} in black and white...")

class NewPrinter(Printer, Fax, Scanner):

def print(self, document):

print(f"Printing {document} in color...")

def fax(self, document):

print(f"Faxing {document}...")

def scan(self, document):

print(f"Scanning {document}...")

Now Printer, Fax, and Scanner are base classes that provide specific interfaces with a single responsibility each. To create OldPrinter, you only inherit the Printer interface. This way, the class won’t have unused methods. To create the ModernPrinter class, you need to inherit from all the interfaces. In short, you’ve segregated the Printer interface.

Note: In Python, you’ll rarely define many abstract base classes as you did in the example above. You may instead rely on duck typing or mixin classes to make your code more Pythonic and flexible.

This class design allows you to create different machines with different sets of functionalities, making your design more flexible and extensible.

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

The dependency inversion principle (DIP) is the last principle in the SOLID set. This principle states that:

Abstractions should not depend upon details. Details should depend upon abstractions.

That sounds pretty complex. Here’s an example that will help to clarify it. Say you’re building an application and have a FrontEnd class to display data to the users in a friendly way. The app currently gets its data from a database, so you end up with the following code:

app_dip.py

class FrontEnd:

def __init__(self, back_end):

self.back_end = back_end

def display_data(self):

data = self.back_end.get_data_from_database()

print("Display data:", data)

class BackEnd:

def get_data_from_database(self):

return "Data from the database"

In this example, the FrontEnd class depends on the BackEnd class and its concrete implementation. You can say that both classes are tightly coupled. This coupling can lead to scalability issues. For example, say that your app is growing fast, and you want the app to be able to read data from a REST API. How would you do that?

You may consider adding a new method to BackEnd to retrieve the data from the REST API. However, that will also require you to modify FrontEnd, which should be closed to modification according to the open-closed principle.

To fix the issue, you can apply the dependency inversion principle and make your classes depend on abstractions rather than on concrete implementations like BackEnd. In this specific example, you can introduce a DataSource class that provides the interface to use in your concrete classes:

app_dip.py

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class FrontEnd:

def __init__(self, data_source):

self.data_source = data_source

def display_data(self):

data = self.data_source.get_data()

print("Display data:", data)

class DataSource(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def get_data(self):

pass

class Database(DataSource):

def get_data(self):

return "Data from the database"

class API(DataSource):

def get_data(self):

return "Data from the API"

In this redesigned code, you’ve added a DataSource class as an abstraction that provides the required interface, consisting of the .get_data() method. Note how FrontEnd now depends on the interface provided by DataSource, which is an abstraction.

Then you define the Database class, which is a concrete implementation for those cases where you want to retrieve the data from your database. This class depends on the DataSource abstraction through inheritance. Finally, you define the API class to support retrieving the data from the REST API. This class also depends on the DataSource abstraction.

Here’s how you can use the FrontEnd class in your code:

>>> from app_dip import API, Database, FrontEnd

>>> db_front_end = FrontEnd(Database())

>>> db_front_end.display_data()

Display data: Data from the database

>>> api_front_end = FrontEnd(API())

>>> api_front_end.display_data()

Display data: Data from the API

Here, you first initialize FrontEnd using a Database object and then again using an API object. Every time you call .display_data(), the result will depend on the concrete data source that you use. Note that you can also change the data source dynamically by reassigning the .data_source attribute in your FrontEnd instance.

Conclusion

You’ve learned a lot about the five SOLID design principles, including how to identify code that violates them and how to refactor the code in adherence to best design practices. You saw good and bad examples related to each principle and learned that applying the SOLID principles can help you improve your object-oriented design in Python.

In this tutorial, you’ve learned how to:

- Understand the meaning and purpose of each SOLID principle

- Identify class designs that violate some of the SOLID principles in Python

- Use the SOLID principles to help you refactor Python code and improve its OOD

With this knowledge, you have a strong foundation of well-established best practices that you should apply when designing your classes and their relationships in Python. By applying these principles, you can create code that’s more maintainable, extensible, scalable, and testable.

Free Bonus: Click here to download sample code so you can build clean, maintainable classes with the SOLID Principles in Python.

Frequently Asked Questions

Now that you have some experience with the SOLID design principles in Python, you can use the questions and answers below to check your understanding and recap what you’ve learned.

These FAQs are related to the most important concepts you’ve covered in this tutorial. Click the Show/Hide toggle beside each question to reveal the answer.

The SOLID design principles are five ideas that guide how you split responsibilities, add features without risky modifications, respect subtype contracts, keep interfaces focused, and depend on abstractions. You use SOLID to design classes that you can maintain, extend, and test with confidence.

You provide each class with one clear reason to change and move unrelated behaviors into separate classes. For example, you keep file I/O in one class and ZIP compression in another, which allows you to simplify testing, improve component reusability, and reduce coupling.

You define an abstract interface that subclasses extend without forcing edits to the existing class.

For example, you create a Shape base with .calculate_area() and add Circle or Square by implementing that method instead of changing .__init__() or .calculate_area() in the base.

You ensure that any subtype (subclass) behaves like its base type (base class) so callers don’t face surprises.

In the shapes example, you avoid making Square a Rectangle when changing .width shouldn’t silently change .height, and you instead share a Shape base with .calculate_area().

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “SOLID Design Principles: Improve Object-Oriented Code in Python” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

SOLID Design Principles: Improve Object-Oriented Code in PythonTest your Python understanding of Liskov substitution, Square–Rectangle pitfalls, and safer API design with polymorphism.