Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Introduction to Git and GitHub for Python

Have you ever worked on a Python project that stopped working after you made a change here or a PEP-8 cleanup there, and you weren’t quite sure how to get it back? Version control systems can help you solve that problem and other related ones. Git is one of the most popular version control systems today.

In this tutorial, I’ll walk you through what Git is, how to use it for your personal projects, and how to use it in conjunction with GitHub to work with other people on larger projects. We’ll look at how to create a repo, how to add both new and modified files, and how to navigate through your project’s history so you can “get back” to when your project was working.

This article assumes you already have Git installed on your system. If you don’t, the excellent Pro Git book has a section on how to do that.

What Is Git?

Git is a distributed version control system (DVCS). Let’s break that down a bit and look at what it means.

Version Control

A version control system (VCS) is a set of tools that track the history of a set of files. This means that you can tell your VCS (Git, in our case) to save the state of your files at any point. Then, you may continue to edit the files and store that state as well. Saving the state is similar to creating a backup copy of your working directory. When using Git, we refer to this saving of state as making a commit.

When you make a commit in Git, you add a commit message that explains at a high level what changes you made in this commit. Git can show you the history of all of the commits and their commit messages. This provides a useful history of what work you have done and can really help pinpoint when a bug crept into the system.

In addition to showing you the log of changes you’ve made, Git also allows you to compare files between different commits. As I mentioned earlier, Git will also allow you to return any file (or all files) to an earlier commit with little effort.

Distributed Version Control

OK, so that’s a version control system. What’s the distributed part? It’s probably easiest to answer that question by starting with a little history. Early version control systems worked by storing all of those commits locally on your hard drive. This collection of commits is called a repository. This solved the “I need to get back to where I was” problem but didn’t scale well for a team working on the same codebase.

As larger groups started working (and networking became more common), VCSs changed to store the repository on a central server that was shared by many developers. While this solved many problems, it also created new ones, like file locking.

Following the lead of a few other products, Git broke with that model. Git does not have a central server that has the definitive version of the repository. All users have a full copy of the repository. This means that getting all of the developers back on the same page can sometimes be tricky, but it also means that developers can work offline most of the time, only connecting to other repositories when they need to share their work.

That last paragraph can seem a little confusing at first, because there are a lot of developers who use GitHub as a central repository from which everyone must pull. This is true, but Git doesn’t impose this. It’s just convenient in some circumstances to have a central place to share the code. The full repository is still stored on all local repos even when you use GitHub.

Basic Usage

Now that we’ve talked about what Git is in general, let’s run through an example and see it in action. We’ll start by working with Git just on our local machine. Once we get the hang of that, we’ll add GitHub and explain how you can interact with it.

Creating a New Repo

To work with Git, you first need to tell it who you are. You can set your username with the git config command:

$ git config --global user.name "your name goes here"

Once that is set up, you will need a repo to work in. Creating a repo is simple. Use the git init command in a directory:

$ mkdir example

$ cd example

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/jima/tmp/example/.git/

Once you have a repo, you can ask Git about it. The Git command you’ll use most frequently is git status. Try that now:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

This shows you a couple of bits of information: which branch you’re on, master (we’ll talk about branches later), and that you have nothing to commit. This last part means that there are no files in this directory that Git doesn’t know about. That’s good, as we just created the directory.

Adding a New File

Now create a file that Git doesn’t know about. With your favorite editor, create the file hello.py, which has just a print statement in it.

# hello.py

print('hello Git!')

If you run git status again, you’ll see a different result:

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

hello.py

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Now Git sees the new file and tells you that it’s untracked. That’s just Git’s way of saying that the file is not part of the repo and is not under version control. We can fix that by adding the file to Git. Use the git add command to make that happen:

$ git add hello.py

$ git status

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: hello.py

Now Git knows about hello.py and lists it under changes to be committed. Adding the file to Git moves it into the staging area (discussed below) and means we can commit it to the repo.

Committing Changes

When you commit changes, you are telling Git to make a snapshot of this state in the repo. Do that now by using the git commit command. The -m option tells Git to use the commit message that follows. If you don’t use -m, Git will bring up an editor for you to create the commit message. In general, you want your commit messages to reflect what has changed in the commit:

$ git commit -m "creating hello.py"

[master (root-commit) 25b09b9] creating hello.py

1 file changed, 3 insertions(+)

create mode 100755 hello.py

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

You can see that the commit command returned a bunch of information, most of which isn’t that useful, but it does tell you that only 1 file changed (which makes sense as we added one file). It also tells you the SHA of the commit (25b09b9). We’ll have an aside about SHA a bit later.

Running the git status command again shows that we have a clean working directory, meaning that all changes are committed to Git.

At this point, we need to stop our tutorial and have a quick chat about the staging area.

Aside: The Staging Area

Unlike many version control systems, Git has a staging area (often referred to as the index). The staging area is how Git keeps track of the changes you want to be in your next commit. When we ran git add above, we told Git that we wanted to move the new file hello.py to the staging area. This change was reflected in git status. The file went from the untracked section to the to be committed section of the output.

Note that the staging area reflects the exact contents of the file when you ran git add. If you modify it again, the file will appear both in the staged and unstaged portions of the status output.

At any point of working with a file in Git (assuming it’s already been committed once), there can be three versions of the file you can work with:

- the version on your hard drive that you are editing

- a different version that Git has stored in your staging area

- the latest version checked in to the repo

All three of these can be different versions of the file. Moving changes to the staging area and then committing them brings all of these versions back into sync.

When I started with Git, I found the staging area a little confusing and a bit annoying. It seemed to add extra steps to the process without adding any benefits. When you’re first learning Git, that’s actually true. After a while, there will be situations where you come to really appreciate having that functionality. Unfortunately, those situations are beyond the scope of this tutorial.

If you’re interested in more detailed info about the staging area, I can recommend this blog post.

.gitignore

The status command is very handy, and you’ll find yourself using it often. But sometimes you’ll find that there are a bunch of files that show up in the untracked section and that you want Git to just not see. That’s where the .gitignore file comes in.

Let’s walk through an example. Create a new Python file in the same directory called myname.py.

# myname.py

def get_name():

return "Jim"

Then modify your hello.py to include myname and call its function:

# hello.py

import myname

name = myname.get_name()

print("hello {}".format(name))

When you import a local module, Python will compile it to bytecode for you and leave that file on your filesystem. In Python 2, it will leave a file called myname.pyc, but we’ll assume you’re running Python 3. In that case it will create a __pycache__ directory and store a pyc file there. That is what’s shown below:

$ ls

hello.py myname.py

$ ./hello.py

hello Jim!

$ ls

hello.py myname.py __pycache__

Now if you run git status, you’ll see that directory in the untracked section. Also note that your new myname.py file is untracked, while the changes you made to hello.py are in a new section called “Changes not staged for commit”. This just means that those changes have not yet been added to the staging area. Let’s try it out:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: hello.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

__pycache__/

myname.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Before we move on to the gitignore file, let’s clean up the mess we’ve made a little bit. First we’ll add the myname.py and hello.py files, just like we did earlier:

$ git add myname.py hello.py

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: hello.py

new file: myname.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

__pycache__/

Let’s commit those changes and finish our clean up:

$ git commit -m "added myname module"

[master 946b99b] added myname module

2 files changed, 8 insertions(+), 1 deletion(-)

create mode 100644 myname.py

Now when we run status, all we see is that __pycache__ directory:

$ git status

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

__pycache__/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

To get all __pycache__ directories (and their contents) to be ignored, we’re going to add a .gitignore file to our repo. This is as simple as it sounds. Edit the file (remember the dot in front of the name!) in your favorite editor.

# .gitignore

__pycache__

Now when we run git status, we no longer see the __pycache__ directory. We do, however, see the new .gitignore! Take a look:

$ git status

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.gitignore

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

That file is just a regular text file and can be added to you repo like any other file. Do that now:

$ git add .gitignore

$ git commit -m "created .gitignore"

[master 1cada8f] created .gitignore

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 .gitignore

Another common entry in the .gitignore file is the directory you store your virtual environments in. You can learn more about virtualenvs here, but the virtualenv directory is usually called env or venv. You can add these to your .gitignore file. If the files or directories are present, they will be ignored. If they are not, then nothing will happen.

It’s also possible to have a global .gitignore file stored in your home directory. This is very handy if your editor likes to leave temporary or backup files in the local directory.

Here’s an example of a simple Python .gitignore file:

# .gitignore

__pycache__

venv

env

.pytest_cache

.coverage

For a more complete example, look here or, if you want to build your own, git help gitignore provides all the details you’ll need.

What NOT to Add to a Git Repo

When you first start working with any version control tool, especially Git, you might be tempted to put everything into the repo. This is generally a mistake. There are limitations to Git as well as security concerns that force you to limit which types of information you add to the repo.

Let’s start with the basic rule of thumb about all version control systems.

Only put source files into version control, never generated files.

In this context, a source file is any file you create, usually by typing in an editor. A generated file is something that the computer creates, usually by processing a source file. For example, hello.py is a source file, while hello.pyc would be a generated file.

There are two reasons for not including generated files in the repo. The first is that doing so is a waste of time and space. The generated files can be recreated at any time and may need to be created in a different form. If someone is using Jython or IronPython while you’re using the Cython interpreter, the .pyc files might be quite different. Committing one particular flavor of files can cause conflict

The second reason for not storing generated files is that these files are frequently larger than the original source files. Putting them in the repo means that everyone now needs to download and store those generated files, even if they’re not using them.

This second point leads to another general rule about Git repos: commit binary files with caution and strongly avoid committing large files. This rule has a lot to do with how Git works.

Git does not store a full copy of each version of each file you commit. Rather, it uses a complicated algorithm based on the differences between subsequent versions of a file to greatly reduce the amount of storage it needs. Binary files (like JPGs or MP3 files) don’t really have good diff tools, so Git will frequently just need to store the entire file each time it is committed.

When you are working with Git, and especially when you are working with GitHub, never put confidential information into a repo, especially one you might share publicly. This is so important that I’m going to say it again:

Caution: Never put confidential information into a public repository on GitHub. Passwords, API keys, and similar items should not be committed to a repo. Someone will find them eventually.

Aside: What is a SHA

When Git stores things (files, directories, commits, etc) in your repo, it stores them in a complicated way involving a hash function. We don’t need to go into the details here, but a hash function takes a thing and produces a unique ID for that thing that is much shorter (20 bytes, in our case). This ID is called a “SHA” in Git. It is not guaranteed to be unique, but for most practical applications it is.

Git uses its hash algorithm to index everything in your repo. Each file has a SHA that reflects the contents of that file. Each directory, in turn, is hashed. If a file in that directory changes, then the SHA of the directory changes too.

Each commit contains the SHA of the top-level directory in your repo along with some other info. That’s how a single 20 byte number describes the entire state of your repo.

You might notice that sometimes Git uses the full 20 character value to show you a SHA:

commit 25b09b9ccfe9110aed2d09444f1b50fa2b4c979c

Sometimes it shows you a shorter version:

[master (root-commit) 25b09b9] creating hello.py

Usually, it will show you the full string of characters, but you don’t always have to use it. The rule for Git is that you only have to give enough characters to ensure that the SHA is unique in your repo. Generally, seven characters is more than enough.

Each time you commit changes to the repo, Git creates a new SHA that describes that state. We’ll look at how SHAs are useful in the next sections.

Git Log

Another very frequently used Git command is git log. Git log shows you the history of the commits that you have made up to this point:

$ git log

commit 1cada8f59b43254f621d1984a9ffa0f4b1107a3b

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Sat Mar 3 13:23:07 2018 -0700

created .gitignore

commit 946b99bfe1641102d39f95616ceaab5c3dc960f9

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Sat Mar 3 13:22:27 2018 -0700

added myname module

commit 25b09b9ccfe9110aed2d09444f1b50fa2b4c979c

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Sat Mar 3 13:10:12 2018 -0700

creating hello.py

As you can see in the listing above, all of the commit messages are shown for our repo in order. The start of each commit is marked with the word “commit” followed by the SHA of that commit. git log gives you the history of each of the SHAs.

Going Back In Time: Checking Out a Particular Version of Your Code

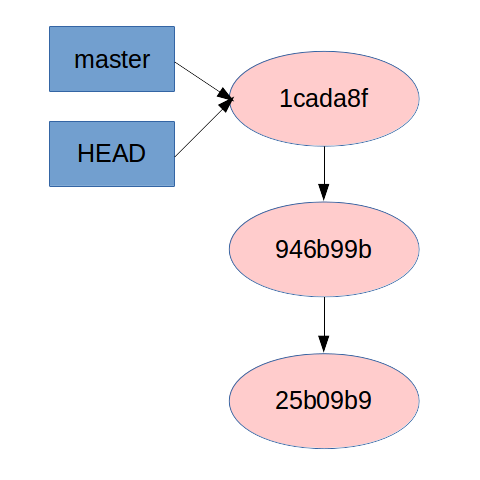

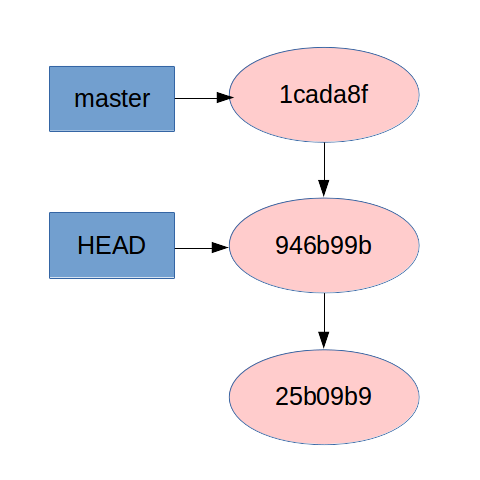

Because Git remembers each commit you’ve made with it’s SHA, you can tell Git to go to any of those commits and view the repo as it existed then. The diagram below shows what Git thinks is in our repo:

Don’t worry about what master and HEAD mean in the diagram. We’ll explain those in just a bit.

To change where we are in our history, we will use the git checkout command to tell Git which SHA we want to look at. Let’s try that:

$ git checkout 946b99bfe1641102d39f95616ceaab5c3dc960f9

Note: checking out '946b99bfe1641102d39f95616ceaab5c3dc960f9'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by performing another checkout.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -b with the checkout command again. Example:

git checkout -b <new-branch-name>

HEAD is now at 946b99b... added myname module

OK, so there’s a LOT of information here that’s confusing. Let’s start by defining some of those terms. Let’s start with HEAD.

HEAD is Git’s name for whatever SHA you happen to be looking at at any time. It does NOT mean what is on your filesystem or what is in your staging area. It means what Git thinks you have checked out. So, if you’ve edited a file, the version on your filesystem is different than the version in HEAD (and yes, HEAD is in ALL CAPS).

Next, we have branch. The easiest way to think about a branch is that it is a label on a SHA. It has a few other properties that are useful, but for now, think of a branch as a SHA label.

Note: Those of you who have worked with other version control systems (I’m looking at you, Subversion) will have a very different idea of what a branch is. Git treats branches differently, and that is a good thing.

When we put all this information together, we see that detached HEAD simply means that your HEAD is pointing to a SHA that does not have a branch (or label) associated with it. Git very nicely tells you how to fix that situation. There will be times when you will want to fix it, and there will be times when you can work in that detached HEAD state just fine.

Let’s get back to our demo. If you look at the state of the system now, you can see that the .gitignore file is no longer present. We went back to the state of the system before we made those changes. Below is the diagram of our repo at this state. Note how the HEAD and master pointers are pointing at different SHAs:

Alright. Now, how do we get back to where we were? There are two ways, one of which you should know already: git checkout 1cada8f. This will take you back to the SHA you were at when you started moving around.

Note: One odd thing, at least in my version of Git, is that it still gives you a detached HEAD warning, even though you’re back to the SHA associated with a branch.

The other way of getting back is more common: check out the branch you were on. Git always starts you off with a branch called master. We’ll learn how to make other branches later but for now we’ll stick with master.

To get back to where you where, you can simply do git checkout master. This will return you to the latest SHA committed to the master branch, which in our case has the commit message “created .gitignore”. To put it another way, git checkout master tells Git to make HEAD point to the SHA marked by the label, or branch, master.

Note that there are several methods for specifying a specific commit. The SHA is probably the easiest to understand. The other methods use different symbols and names to specify how to get to a specific commit from a known place, like HEAD. I won’t be going into those details in this tutorial, but if you’d like more details you can find them here.

Branching Basics

Let’s talk a little more about branches. Branches provide a way for you to keep separate streams of development apart. While this can be useful when you’re working alone, it’s almost essential when you’re working on team.

Imagine that I’m working in a small team and have a feature to add to the project. While I’m working on it, I don’t want to add my changes to master as it still doesn’t work correctly and might mess up my team members.

I could just wait to commit the changes until I’m completely finished, but that’s not very safe and not always practical. So, instead of working on master, I’ll create a new branch:

$ git checkout -b my_new_feature

Switched to a new branch 'my_new_feature'

$ git status

On branch my_new_feature

nothing to commit, working directory clean

We used the -b option on the checkout command to tell Git we wanted it to create a new branch. As you can see above, running git status in our branch shows us that the branch name has, indeed, changed. Let’s look at the log:

$ git log

commit 1cada8f59b43254f621d1984a9ffa0f4b1107a3b

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Thu Mar 8 20:57:42 2018 -0700

created .gitignore

commit 946b99bfe1641102d39f95616ceaab5c3dc960f9

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Thu Mar 8 20:56:50 2018 -0700

added myname module

commit 25b09b9ccfe9110aed2d09444f1b50fa2b4c979c

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Thu Mar 8 20:53:59 2018 -0700

creating hello.py

As I hope you expected, the log looks exactly the same. When you create a new branch, the new branch will start at the location you were at. In this case, we were at the top of master, 1cada8f59b43254f621d1984a9ffa0f4b1107a3b, so that’s where the new branch starts.

Now, let’s work on that feature. Make a change to the hello.py file and commit it. I’ll show you the commands for review, but I’ll stop showing you the output of the commands for things you’ve already seen:

$ git add hello.py

$ git commit -m "added code for feature x"

Now if you do git log, you’ll see that our new commit is present. In my case, it has a SHA 4a4f4492ded256aa7b29bf5176a17f9eda66efbb, but your repo is very likely to have a different SHA:

$ git log

commit 4a4f4492ded256aa7b29bf5176a17f9eda66efbb

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Thu Mar 8 21:03:09 2018 -0700

added code for feature x

commit 1cada8f59b43254f621d1984a9ffa0f4b1107a3b

... the rest of the output truncated ...

Now switch back to the master branch and look at the log:

git checkout master

git log

Is the new commit “added code for feature x” there?

Git has a built-in way to compare the state of two branches so you don’t have to work so hard. It’s the show-branch command. Here’s what it looks like:

$ git show-branch my_new_feature master

* [my_new_feature] added code for feature x

! [master] created .gitignore

--

* [my_new_feature] added code for feature x

*+ [master] created .gitignore

The chart it generates is a little confusing at first, so let’s walk though it in detail. First off, you call the command by giving it the name of two branches. In our case that was my_new_feature and master.

The first two lines of the output are the key to decoding the rest of the text. The first non-space character on each line is either * or ! followed by the name of the branch, and then the commit message for the most recent commit on that branch. The * character is used to indicate that the branch is currently checked-out while the ! is used for all other branches. The character is in the column matching commits in the table below.

The third line is a separator.

Starting on the fourth line, there are commits that are in one branch but not the other. In our current case, this is pretty easy. There’s one commit in my_new_feature that’s not in master. You can see that on the fourth line. Notice how that line starts with a * in the first column. This is to indicate which branch this commit is in.

Finally, the last line of the output shows the first common commit for the two branches.

This example is pretty easy. To make a better example, I’ve made it more interesting by adding a few more commits to my_new_feature and a few to master. That makes the output look like:

$ git show-branch my_new_feature master

* [my_new_feature] commit 4

! [master] commit 3

--

* [my_new_feature] commit 4

* [my_new_feature^] commit 1

* [my_new_feature~2] added code for feature x

+ [master] commit 3

+ [master^] commit 2

*+ [my_new_feature~3] created .gitignore

Now you can see that there are different commits in each branch. Note that the [my_new_feature~2] text is one of the commit selection methods I mentioned earlier. If you’d rather see the SHAs, you can have it show them by adding the –sha1-name option to the command:

$ git show-branch --sha1-name my_new_feature master

* [my_new_feature] commit 4

! [master] commit 3

--

* [6b6a607] commit 4

* [12795d2] commit 1

* [4a4f449] added code for feature x

+ [de7195a] commit 3

+ [580e206] commit 2

*+ [1cada8f] created .gitignore

Now you’ve got a branch with a bunch of different commits on it. What do you do when you finally finish that feature and are ready to get it to the rest of your team?

There are three main ways to get commits from one branch to another: merging, rebasing, and cherry-picking. We’ll cover each of these in turn in the next sections.

Merging

Merging is the simplest of the three to understand and use. When you do a merge, Git will create a new commit that combines the top SHAs of two branches if it needs to. If all of the commits in the other branch are ahead (based on) the top of the current branch, it will just do a fast-foward merge and place those new commits on this branch.

Let’s back up to the point where our show-branch output looked like this:

$ git show-branch --sha1-name my_new_feature master

* [my_new_feature] added code for feature x

! [master] created .gitignore

--

* [4a4f449] added code for feature x

*+ [1cada8f] created .gitignore

Now, we want to get that commit 4a4f449 to be on master. Check out master and run the git merge command there:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git merge my_new_feature

Updating 1cada8f..4a4f449

Fast-forward

hello.py | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Since we were on branch master, we did a merge of the my_new_feature branch to us. You can see that this is a fast forward merge and which files were changed. Let’s look at the log now:

commit 4a4f4492ded256aa7b29bf5176a17f9eda66efbb

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Thu Mar 8 21:03:09 2018 -0700

added code for feature x

commit 1cada8f59b43254f621d1984a9ffa0f4b1107a3b

Author: Jim Anderson <jima@example.com>

Date: Thu Mar 8 20:57:42 2018 -0700

created .gitignore

[rest of log truncated]

If we had made changes to master before we merged, Git would have created a new commit that was the combination of the changes from the two branches.

One of the things Git is fairly good at is understanding the common ancestors of different branches and automatically merging changes together. If the same section of code has been modified in both branches, Git can’t figure out what to do. When this happens, it stops the merge part way through and gives you instructions for how to fix the issue. This is called a merge conflict.

Rebasing

Rebasing is similar to merging but behaves a little differently. In a merge, if both branches have changes, then a new merge commit is created. In rebasing, Git will take the commits from one branch and replay them, one at a time, on the top of the other branch.

I won’t do a detailed demo of rebasing here because setting up a demo to show this is a bit tricky in text and because there is an excellent web page that covers the topic well and that I’ll reference at the end of this section.

Cherry-Picking

Cherry picking is another method for moving commits from one branch to another. Unlike merging and rebasing, with cherry-picking you specify exactly which commits you mean. The easiest way to do this is just specifying a single SHA:

$ git cherry-pick 4a4f4492ded256aa7b29bf5176a17f9eda66efbb

This tells Git to take the changes that went into 4a4f449 and apply them to the current branch.

This feature can be very handy when you want a specific change but not the entire branch that change was made on.

Quick Tip About Branching: I can’t leave this topic without recommending an excellent resource for learning about Git branches. Learn Git Branching has a set of exercises using graphical representations of commits and branches to clearly explain the difference between merging, rebasing, and cherry-picking. I highly recommend spending some time working through these exercises.

Working with Remote Repos

All of the commands we’ve discussed up to this point work with only your local repo. They don’t do any communication to a server or over the network. It turns out that there are only four major Git commands which actually talk to remote repos:

clonefetchpullpush

That’s it. Everything else is done on your local machine. (OK, to be completely accurate, there are other commands that talk to remotes, but they don’t fall into the basic category.)

Let’s look at each of these commands in turn.

Clone

Git clone is the command you use when you have the address of a known repository and you want to make a local copy. For this example, let’s use a small repo I have on my GitHub account, github-playground.

The GitHub page for that repo lives here. On that page you will find a “Clone or Download” button which gives you the URI to use with the git clone command. If you copy that, you can then clone the repo with:

git clone git@github.com:jima80525/github-playground.git

Now you have a complete repository of that project on your local machine. This includes all of the commits and all of the branches ever made on it. (Note: This repo was used by some friends while they were learning Git. I copied or forked it from someone else.)

If you want to play with the other remote commands, you should create a new repo on GitHub and follow the same steps. You are welcome to fork the github-playground repo to your account and use that. Forking on GitHub is done by clicking the “fork” button in the UI.

Fetch

To explain the fetch command clearly, we need to take a step back and talk about how Git manages the relationship between your local repo and a remote repo. This next part is background, and while it’s not something you’ll use on a day-to-day basis, it will make the difference between fetch and pull make more sense.

When you clone a new repo, Git doesn’t just copy down a single version of the files in that project. It copies the entire repository and uses that to create a new repository on your local machine.

Git does not make local branches for you except for master. However, it does keep track of the branches that were on the server. To do that, Git creates a set of branches that all start with remotes/origin/<branch_name>.

Only rarely (almost never), will you check out these remotes/origin branches, but it’s handy to know that they are there. Remember that every branch that existed on the remote when you cloned the repo will have a branch in remotes/origin.

When you create a new branch and the name matches an existing branch on the server, Git will mark you local branch as a tracking branch that is associated with a remote branch. We’ll see how that is useful when we get to pull.

Now that you know about the remotes/origin branches, understanding git fetch will be pretty easy. All fetch does is update all of the remotes/origin branches. It will modify only the branches stored in remotes/origin and not any of your local branches.

Pull

Git pull is simply the combination of two other commands. First, it does a git fetch to update the remotes/origin branches. Then, if the branch you are on is tracking a remote branch, then it does a git merge of the corresponding remote/origin branch to your branch.

For example, say you were on the my_new_feature branch, and your coworker had just added some code to it on the server. If you do a git pull, Git will update ALL of the remotes/origin branches and then do a git merge remotes/origin/my_new_feature, which will get the new commit onto the branch you’re on!

There are, of course, some limitations here. Git won’t let you even try to do a git pull if you have modified files on your local system. That can create too much of a mess.

If you have commits on your local branch, and the remote also has new commits (ie “the branches have diverged”), then the git merge portion of the pull will create a merge commit, just as we discussed above.

Those of you who have been reading closely will see that you can also have Git do a rebase instead of a merge by doing git pull -r.

Push

As you have probably guessed, git push is just the opposite of git pull. Well, almost the opposite. Push sends the info about the branch you are pushing and asks the remote if it would like to update its version of that branch to match yours.

Generally, this amounts to you pushing your new changes up to the server. There are a lot of details and complexity here involving exactly what a fast-forward commit is.

There is a fantastic write-up here. The gist of it is that git push makes your new commits available on the remote server.

Putting It All Together: Simple Git Workflow

At this point, we’ve reviewed several basic Git commands and how you might use them. I’ll wrap up with a quick description of a possible workflow in Git. This workflow assumes you are working on your local repo and have a remote repo to which you will push changes. It can be GitHub, but it will work the same with other remote repos. It assumes you’ve already cloned the repo.

git status– Make sure your current area is clean.git pull– Get the latest version from the remote. This saves merging issues later.- Edit your files and make your changes. Remember to run your linter and do unit tests!

git status– Find all files that are changed. Make sure to watch untracked files too!git add [files]– Add the changed files to the staging area.git commit -m "message"– Make your new commit.git push origin [branch-name]– Push your changes up to the remote.

This is one of the more basic flows through the system. There are many, many ways to use Git, and you’ve just scratched the surface with this tutorial. If you use Vim or Sublime as your editor, you might want to checkout these tutorials, which will show you how to get plugins to integrate Git into your editor:

- VIM and Python – A Match Made in Heaven

- Setting Up Sublime Text 3 for Full Stack Python Development

- Emacs – The Best Python Editor?

If you’d like to take a deeper dive into Git, I can recommend these books:

- The free, online Pro Git is a very handy reference.

- For those of you who like to read on paper, there’s a print version of Pro Git and I found O’Reilly’s Version Control with Git to be useful.

You should also check out the Real Python Podcast Episode 179: Improving Your Git Developer Experience in Python with Adam Johnson.

Finally, if you’re interested in harnessing the power of artificial intelligence in your coding journey, then you might want to play around with GitHub Copilot.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Introduction to Git and GitHub for Python