Sometimes when you’re working with several different dictionaries, you need to group and manage them as a single one. In other situations, you can have multiple dictionaries representing different scopes or contexts and need to handle them as a single dictionary that allows you to access the underlying data following a given order or priority. In those cases, you can take advantage of Python’s ChainMap from the collections module.

ChainMap groups multiple dictionaries and mappings in a single, updatable view with dictionary-like behavior. Additionally, ChainMap provides features that allow you to efficiently manage various dictionaries, define key lookup priorities, and more.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to:

- Create

ChainMapinstances in your Python programs - Explore the differences between

ChainMapanddict - Use

ChainMapto work with several dictionaries as one - Manage key lookup priorities with

ChainMap

To get the most out of this tutorial, you should know the basics of working with dictionaries and lists in Python.

By the end of the journey, you’ll find a few practical examples that will help you better understand the most relevant features and use cases of ChainMap.

Free Bonus: 5 Thoughts On Python Mastery, a free course for Python developers that shows you the roadmap and the mindset you’ll need to take your Python skills to the next level.

Getting Started With Python’s ChainMap

Python’s ChainMap was added to collections in Python 3.3 as a handy tool for managing multiple scopes and contexts. This class allows you to group several dictionaries and other mappings together to make them logically appear and behave as one. It creates a single updatable view that works similar to a regular dictionary but with some internal differences.

ChainMap doesn’t merge its mappings together. Instead, it keeps them in an internal list of mappings. Then ChainMap reimplements common dictionary operations on top of that list. Since the internal list holds references to the original input mapping, any changes in those mappings affect the ChainMap object as a whole.

Storing the input mappings in a list allows you to have duplicate keys in a given chain map. If you perform a key lookup, then ChainMap searches the list of mappings until it finds the first occurrence of the target key. If the key is missing, then you get a KeyError as usual.

Storing the mappings in a list truly shines when you need to manage nested scopes, where each mapping represents a specific scope or context.

To better understand what scopes and contexts are about, think about how Python resolves names. When Python looks for a name, it searches in locals(), globals(), and finally builtins until it finds the first occurrence of the target name. If the name doesn’t exist, then you get a NameError. Dealing with scopes and contexts is the most common kind of problem you can solve with ChainMap.

When you’re working with ChainMap, you can chain several dictionaries with keys that are either disjoint or intersecting.

In the first case, ChainMap allows you to treat all your dictionaries as one. So, you can access the key-value pairs as if you were working with a single dictionary. In the second case, besides managing your dictionaries as one, you can also take advantage of the internal list of mappings to define some sort of access priority for repeated keys across your dictionaries. That’s why ChainMap objects are great for handling multiple contexts.

A curious behavior of ChainMap is that mutations, such as updating, adding, deleting, clearing, and popping keys, act only on the first mapping in the internal list of mappings. Here’s a summary of the main features of ChainMap:

- Builds an updatable view from several input mappings

- Provides almost the same interface as a dictionary, but with some extra features

- Doesn’t merge the input mappings but instead keeps them in an internal public list

- Sees external changes in the input mappings

- Can contain repeated keys with different values

- Searches keys sequentially through the internal list of mappings

- Throws a

KeyErrorwhen a key is missing after searching the entire list of mappings - Performs mutations only on the first mapping in the internal list

In this tutorial, you’ll learn a lot more about all these cool features of ChainMap. The following section will guide you through how to create new instances of ChainMap in your code.

Instantiating ChainMap

To create ChainMap in your Python code, you first need to import the class from collections and then call it as usual. The class initializer can take zero or more mappings as arguments. With no arguments, it initializes a chain map with an empty dictionary inside:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> from collections import OrderedDict, defaultdict

>>> # Use no arguments

>>> ChainMap()

ChainMap({})

>>> # Use regular dictionaries

>>> numbers = {"one": 1, "two": 2}

>>> letters = {"a": "A", "b": "B"}

>>> ChainMap(numbers, letters)

ChainMap({'one': 1, 'two': 2}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

>>> ChainMap(numbers, {"a": "A", "b": "B"})

ChainMap({'one': 1, 'two': 2}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

>>> # Use other mappings

>>> numbers = OrderedDict(one=1, two=2)

>>> letters = defaultdict(str, {"a": "A", "b": "B"})

>>> ChainMap(numbers, letters)

ChainMap(

OrderedDict([('one', 1), ('two', 2)]),

defaultdict(<class 'str'>, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

)

Here, you create several ChainMap objects using different combinations of mappings. In each case, ChainMap returns a single dictionary-like view of all the input mappings. Note that you can use any type of mapping, such as OrderedDict and defaultdict.

You can also create ChainMap objects using the class method .fromkeys(). This method can take an iterable of keys and an optional default value for all the keys:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> ChainMap.fromkeys(["one", "two","three"])

ChainMap({'one': None, 'two': None, 'three': None})

>>> ChainMap.fromkeys(["one", "two","three"], 0)

ChainMap({'one': 0, 'two': 0, 'three': 0})

If you call .fromkeys() on ChainMap with an iterable of keys as an argument, then you get a chain map with a single dictionary. The keys come from the input iterable, and the values default to None. Optionally, you can pass a second argument to .fromkeys() to provide a sensible default value for every key.

Running Dictionary-Like Operations

ChainMap supports the same API as regular dictionaries for accessing existing keys. Once you have a ChainMap object, you can retrieve existing keys with dictionary-style key lookup, or you can use .get():

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> numbers = {"one": 1, "two": 2}

>>> letters = {"a": "A", "b": "B"}

>>> alpha_num = ChainMap(numbers, letters)

>>> alpha_num["two"]

2

>>> alpha_num.get("a")

'A'

>>> alpha_num["three"]

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

KeyError: 'three'

A key lookup searches all the mappings in the target chain map until it finds the desired key. If the key doesn’t exist, then you get the usual KeyError. Now, how does a lookup operation behave when you have duplicate keys? In that case, you get the first occurrence of the target key:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"dogs": 4, "cats": 3, "turtles": 1}

>>> pets = ChainMap(for_adoption, vet_treatment)

>>> pets["dogs"]

10

>>> pets.get("cats")

7

>>> pets["turtles"]

1

When you access a duplicate key, such as "dogs" and "cats", the chain map only returns the first occurrence of that key. Internally, lookup operations search the input mappings in the same order they appear in the internal list of mappings, which is also the exact order you pass them into the class’s initializer.

This general behavior also applies to iteration:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"dogs": 4, "cats": 3, "turtles": 1}

>>> pets = ChainMap(for_adoption, vet_treatment)

>>> for key, value in pets.items():

... print(key, "->", value)

...

dogs -> 10

cats -> 7

turtles -> 1

pythons -> 3

The for loop iterates over the dictionaries in pets and prints the first occurrence of each key-value pair. You can also iterate through the dictionary directly or with .keys() and .values() as you can do with any dictionary:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"dogs": 4, "cats": 3, "turtles": 1}

>>> pets = ChainMap(for_adoption, vet_treatment)

>>> for key in pets:

... print(key, "->", pets[key])

...

dogs -> 10

cats -> 7

turtles -> 1

pythons -> 3

>>> for key in pets.keys():

... print(key, "->", pets[key])

...

dogs -> 10

cats -> 7

turtles -> 1

pythons -> 3

>>> for value in pets.values():

... print(value)

...

10

7

1

3

Again, the behavior is the same. Every iteration goes through the first occurrence of each key, item, and value in the underlying chain map.

ChainMap also supports mutations. In other words, it allows you to update, add, delete, and pop key-value pairs. The difference in this case is that these operations act on the first mapping only:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> numbers = {"one": 1, "two": 2}

>>> letters = {"a": "A", "b": "B"}

>>> alpha_num = ChainMap(numbers, letters)

>>> alpha_num

ChainMap({'one': 1, 'two': 2}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

>>> # Add a new key-value pair

>>> alpha_num["c"] = "C"

>>> alpha_num

ChainMap({'one': 1, 'two': 2, 'c': 'C'}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

>>> # Update an existing key

>>> alpha_num["b"] = "b"

>>> alpha_num

ChainMap({'one': 1, 'two': 2, 'c': 'C', 'b': 'b'}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

>>> # Pop keys

>>> alpha_num.pop("two")

2

>>> alpha_num.pop("a")

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

KeyError: "Key not found in the first mapping: 'a'"

>>> # Delete keys

>>> del alpha_num["c"]

>>> alpha_num

ChainMap({'one': 1, 'b': 'b'}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

>>> del alpha_num["a"]

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

KeyError: "Key not found in the first mapping: 'a'"

>>> # Clear the dictionary

>>> alpha_num.clear()

>>> alpha_num

ChainMap({}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

Operations that mutate the content of a given chain map only affect the first mapping, even if the key you’re trying to mutate exists in other mappings in the list. For example, when you try to update "b" in the second mapping, what really happens is that you add a new key to the first dictionary.

You can take advantage of this behavior to create updatable chain maps that don’t modify your original input dictionaries. In this case, you can use an empty dictionary as the first argument to ChainMap:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> numbers = {"one": 1, "two": 2}

>>> letters = {"a": "A", "b": "B"}

>>> alpha_num = ChainMap({}, numbers, letters)

>>> alpha_num

ChainMap({}, {'one': 1, 'two': 2}, {'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'})

>>> alpha_num["comma"] = ","

>>> alpha_num["period"] = "."

>>> alpha_num

ChainMap(

{'comma': ',', 'period': '.'},

{'one': 1, 'two': 2},

{'a': 'A', 'b': 'B'}

)

Here, you use an empty dictionary ({}) to create alpha_num. This ensures that the changes you perform on alpha_num will never affect your two original input dictionaries, numbers and letters, and will only affect the empty dictionary at the beginning of the list.

Merging vs Chaining Dictionaries

As an alternative to chaining multiple dictionaries with ChainMap, you can consider merging them together using dict.update():

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> # Chain dictionaries with ChainMap

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"hamsters": 2, "turtles": 1}

>>> ChainMap(for_adoption, vet_treatment)

ChainMap(

{'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3},

{'hamsters': 2, 'turtles': 1}

)

>>> # Merge dictionaries with .update()

>>> pets = {}

>>> pets.update(for_adoption)

>>> pets.update(vet_treatment)

>>> pets

{'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3, 'hamsters': 2, 'turtles': 1}

In this specific example, you get similar results when you build a chain map and an equivalent dictionary from two existing dictionaries with unique keys.

Merging dictionaries with .update() has pros and cons compared with chaining them with ChainMap. The first and most important drawback is that you’re throwing out the ability to manage and prioritize the access to repeated keys using multiple scopes or contexts. With .update(), the last value you provide for a given key will always prevail:

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"cats": 2, "dogs": 1}

>>> # Merge dictionaries with .update()

>>> pets = {}

>>> pets.update(for_adoption)

>>> pets.update(vet_treatment)

>>> pets

{'dogs': 1, 'cats': 2, 'pythons': 3}

Regular dictionaries can’t store repeated keys. Every time you call .update() with a value for an existing key, that key is updated with the new value. In this case, you lose the ability to prioritize the access to duplicate keys using different scopes.

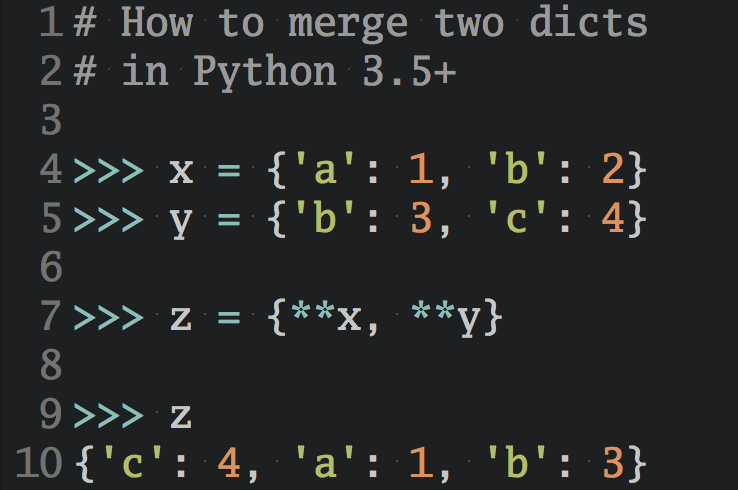

Note: Since Python 3.5, you can also merge dictionaries together using the dictionary unpacking operator (**). Additionally, if you’re using Python 3.9, then you can use the dictionary union operator (|) to merge two dictionaries into a new one.

Now suppose you have n different mappings with at most m keys each. Creating a ChainMap object from them would take O(n) execution time, while retrieving a key would take O(n) in the worst-case scenario, in which the target key is in the last dictionary of the internal list of mappings.

Alternatively, creating a regular dictionary using .update() in a loop would take O(nm), while retrieving a key from the final dictionary would take O(1).

The conclusion is that, if you often create chains of dictionaries and only perform a few key lookups each time, then you should use ChainMap. If it’s the other way around, then use regular dictionaries unless you require duplicate keys or multiple scopes.

Another difference between merging and chaining dictionaries is that when you use ChainMap, external changes in the input dictionaries affect the underlying chain, which isn’t the case with merged dictionaries.

Exploring Additional Features of ChainMap

ChainMap provides mostly the same API and features as a regular Python dictionary, with some subtle differences that you already know about. ChainMap also supports some additional features that are specific to its design and goals.

In this section, you’ll learn about all of these additional features. You’ll learn how they can help you manage different scopes and contexts when you’re accessing the key-value pairs in your dictionaries.

Managing the List of Mappings With .maps

ChainMap stores all the input mappings in an internal list. This list is accessible through a public instance attribute called .maps, and it’s user-updatable. The order of mappings in .maps matches the order in which you pass them into ChainMap. This order defines the search order when you perform key lookup operations.

Here’s an example of how you can access .maps:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"dogs": 4, "turtles": 1}

>>> pets = ChainMap(for_adoption, vet_treatment)

>>> pets.maps

[{'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3}, {'dogs': 4, 'turtles': 1}]

Here, you use .maps to access the internal list of mappings that pets holds. This list is a regular Python list, so you can add and remove mappings manually, iterate through the list, change the order of the mappings, and more:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"cats": 1}

>>> pets = ChainMap(for_adoption, vet_treatment)

>>> pets.maps.append({"hamsters": 2})

>>> pets.maps

[{'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3}, {"cats": 1}, {'hamsters': 2}]

>>> del pets.maps[1]

>>> pets.maps

[{'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3}, {'hamsters': 2}]

>>> for mapping in pets.maps:

... print(mapping)

...

{'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3}

{'hamsters': 2}

In these examples, you first add a new dictionary to .maps using .append(). Then you use the del keyword to remove the dictionary at position 1. You can manage .maps as you would any regular Python list.

Note: The internal list of mappings, .maps, will always contain at least one mapping. For example, if you create an empty chain map using ChainMap() without arguments, then the list will store an empty dictionary.

You can use .maps for iterating over all your mappings while you perform actions on them. The possibility of iterating through the list of mappings allows you to perform different actions on each mapping. With this option, you can work around the default behavior of mutating only the first mapping in the list.

An interesting example is that you can reverse the order of the current list of mappings using .reverse():

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> for_adoption = {"dogs": 10, "cats": 7, "pythons": 3}

>>> vet_treatment = {"cats": 1}

>>> pets = ChainMap(for_adoption, vet_treatment)

>>> pets

ChainMap({'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3}, {'cats': 1})

>>> pets.maps.reverse()

>>> pets

ChainMap({'cats': 1}, {'dogs': 10, 'cats': 7, 'pythons': 3})

Reversing the internal list of mappings allows you to reverse the search order when you look up a given key in the chain map. Now when you look for "cats", you get the number of cats under veterinarian treatment instead of the cats that are ready for adoption.

Adding New Subcontexts With .new_child()

ChainMap also implements .new_child(). This method optionally takes a mapping as an argument and returns a new ChainMap instance containing the input mapping followed by all of the current mappings in the underlying chain map:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> mom = {"name": "Jane", "age": 31}

>>> dad = {"name": "John", "age": 35}

>>> family = ChainMap(mom, dad)

>>> family

ChainMap({'name': 'Jane', 'age': 31}, {'name': 'John', 'age': 35})

>>> son = {"name": "Mike", "age": 0}

>>> family = family.new_child(son)

>>> for person in family.maps:

... print(person)

...

{'name': 'Mike', 'age': 0}

{'name': 'Jane', 'age': 31}

{'name': 'John', 'age': 35}

Here, .new_child() returns a new ChainMap object containing a new mapping, son, followed by the old mappings, mom and dad. Note that the new mapping now holds the first position in the internal list of mappings, .maps.

With .new_child(), you can create a subcontext that you can update without altering any of the existing mappings. For example, if you call .new_child() without an argument, then it uses an empty dictionary and places it at the beginning of .maps. After this, you can perform any mutations over your new empty mapping, keeping the rest of the mapping read-only.

Skipping Subcontexts With .parents

Another interesting feature of ChainMap is .parents. This property returns a new ChainMap instance with all the mappings in the underlying chain map except the first one. This feature is useful for skipping the first mapping when you’re searching for keys in a given chain map:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> mom = {"name": "Jane", "age": 31}

>>> dad = {"name": "John", "age": 35}

>>> son = {"name": "Mike", "age": 0}

>>> family = ChainMap(son, mom, dad)

>>> family

ChainMap(

{'name': 'Mike', 'age': 0},

{'name': 'Jane', 'age': 31},

{'name': 'John', 'age': 35}

)

>>> family.parents

ChainMap({'name': 'Jane', 'age': 31}, {'name': 'John', 'age': 35})

In this example, you use .parents to skip the first dictionary containing the son’s data. In a way, .parents does the inverse of .new_child(). The former removes a dictionary, while the latter adds a new dictionary to the beginning of the list. In both cases, you get a new chain map.

Managing Scopes and Contexts With ChainMap

Arguably, the primary use case of ChainMap is to provide an efficient way to manage multiple scopes or contexts and handle access priorities for duplicate keys. This feature is useful when you have several dictionaries that store duplicate keys and you want to define the order in which your code will access them.

In the ChainMap documentation, you’ll find a classic example that emulates how Python resolves variable names in the different namespaces.

When Python is looking for a name, it searches the local, global, and built-in scope sequentially, following that same order until it finds the target name. Python scopes are dictionaries that map names to objects.

To emulate Python’s internal lookup chain, you can use a chain map:

>>> import builtins

>>> # Shadow input with a global name

>>> input = 42

>>> pylookup = ChainMap(locals(), globals(), vars(builtins))

>>> # Retrieve input from the global namespace

>>> pylookup["input"]

42

>>> # Remove input from the global namespace

>>> del globals()["input"]

>>> # Retrieve input from the builtins namespace

>>> pylookup["input"]

<built-in function input>

In this example, you first create a global variable called input that shadows the built-in input() function in the builtins scope. Then you create pylookup as a chain map containing the three dictionaries that hold each Python scope.

When you retrieve input from pylookup, you get the value 42 from the global scope. If you remove the input key from the globals() dictionary and access it again, then you get the built-in input() function from the builtins scope, which has the lowest priority in Python’s lookup chain.

Similarly, you can use ChainMap to define and manage the key lookup order for duplicate keys. This allows you to prioritize the access to the desired instance of a duplicate key.

Tracking ChainMap in the Standard Library

The origin of ChainMap is closely related to a performance issue in ConfigParser, which lives in the configparser module in the standard library. With ChainMap, the core Python developers dramatically improved the performance of this module as a whole by optimizing the implementation of ConfigParser.get().

You can also find ChainMap as part of Template in the string module. This class takes a string template as an argument and allows you to perform string substitutions as described in PEP 292. The input string template contains embedded identifiers that you can later substitute with actual values:

>>> import string

>>> greeting = "Hey $name, welcome to $place!"

>>> template = string.Template(greeting)

>>> template.substitute({"name": "Jane", "place": "the World"})

'Hey Jane, welcome to the World!'

When you provide values for name and place through a dictionary, .substitute() replaces them in the template string. Additionally, .substitute() can take values as keyword arguments (**kwargs), which can cause name collisions in some situations:

>>> import string

>>> greeting = "Hey $name, welcome to $place!"

>>> template = string.Template(greeting)

>>> template.substitute(

... {"name": "Jane", "place": "the World"},

... place="Real Python"

... )

'Hey Jane, welcome to Real Python!'

In this example, .substitute() replaces place with the value you provide as a keyword argument instead of the value in the input dictionary. If you dig a little bit into the code of this method, then you see that it uses ChainMap to efficiently manage the priority of input values when a name collision occurs.

Here’s a source code fragment from .substitute():

# string.py

# Snip...

from collections import ChainMap as _ChainMap

_sentinel_dict = {}

class Template:

"""A string class for supporting $-substitutions."""

# Snip...

def substitute(self, mapping=_sentinel_dict, /, **kws):

if mapping is _sentinel_dict:

mapping = kws

elif kws:

mapping = _ChainMap(kws, mapping)

# Snip...

Here, the highlighted line does the magic. It uses a chain map that takes two dictionaries, kws and mapping, as arguments. By placing kws as the first argument, the method sets the priority for duplicate identifiers in the input data.

Putting Python’s ChainMap Into Action

So far, you’ve learned how to use ChainMap to work with multiple dictionaries as one. You’ve also learned about the features of ChainMap and how different from regular dictionaries this class is. The use cases of ChainMap are fairly specific. They include:

- Grouping multiple dictionaries in a single view efficiently

- Searching through multiple dictionaries with a certain priority

- Providing a chain of default values and managing their priority

- Improving the performance of code that frequently computes subsets of a dictionary

In this section, you’ll code a few practical examples that will help you get a better idea of how to use ChainMap to solve real-world problems.

Accessing Multiple Inventories as One

The first example you’ll code uses ChainMap to search multiple dictionaries in a single view efficiently. In this case, you would assume you have a bunch of independent dictionaries with unique keys across them.

Say you’re running a store that sells fruits and vegetables. You’ve coded a Python application to manage your inventories. The application reads from a database and returns two dictionaries containing data about the prices of fruits and vegetables, respectively. You need an efficient way to group and manage this data in a single dictionary.

After some research, you end up using ChainMap:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> fruits_prices = {"apple": 0.80, "grape": 0.40, "orange": 0.50}

>>> veggies_prices = {"tomato": 1.20, "pepper": 1.30, "onion": 1.25}

>>> prices = ChainMap(fruits_prices, veggies_prices)

>>> order = {"apple": 4, "tomato": 8, "orange": 4}

>>> for product, units in order.items():

... price = prices[product]

... subtotal = units * price

... print(f"{product:6}: ${price:.2f} × {units} = ${subtotal:.2f}")

...

apple : $0.80 × 4 = $3.20

tomato: $1.20 × 8 = $9.60

orange: $0.50 × 4 = $2.00

In this example, you use a ChainMap to create a single dictionary-like object that groups data from fruits_prices and veggies_prices. This allows you to access the underlying data as if you effectively had a single dictionary. The for loop iterates over the products in a given order. Then it computes the subtotal to pay per type of product and prints it on your screen.

You might think to group the data in a new dictionary, using .update() in a loop. This could work just fine when you have a limited variety of products and a small inventory. However, if you manage many products of different types, then using .update() to build a new dictionary could be inefficient compared with ChainMap.

Using ChainMap to solve this kind of problem can also help you define priorities for products of different batches, allowing you to manage your inventories in a First-In/First-Out (FIFO) fashion.

Prioritizing Command-Line Apps Settings

ChainMap is especially helpful in managing default configuration values in your applications. As you already know, one of the main features of ChainMap is that it allows you to set priorities for key lookup operations. This sounds like the right tool for solving the problem of managing configurations in your applications.

For example, say you’re working on a command-line interface (CLI) application. The application allows the user to specify a proxy service for connecting to the Internet. The settings priorities are:

- Command-line options (

--proxy,-p) - Local configuration files in the user’s home directory

- System-wide proxy configuration

If the user supplies a proxy at the command line, then the application must use that proxy. Otherwise, the application should use the proxy provided in the next configuration object, and so on. This is one of the most common use cases of ChainMap. In this situation, you can do the following:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> cmd_proxy = {} # The user doesn't provide a proxy

>>> local_proxy = {"proxy": "proxy.local.com"}

>>> system_proxy = {"proxy": "proxy.global.com"}

>>> config = ChainMap(cmd_proxy, local_proxy, system_proxy)

>>> config["proxy"]

'proxy.local.com'

ChainMap allows you to define the appropriate priority for the application’s proxy configuration. A key lookup searches cmd_proxy, then local_proxy, and finally system_proxy, returning the first instance of the key at hand. In the example, the user doesn’t provide a proxy at the command line, so the application takes the proxy from local_proxy, which is the next settings provider in the list.

Managing Default Argument Values

Another use case of ChainMap is to manage default argument values in your methods and functions. Say you’re coding an application to manage the data about the employees in your company. You have the following class, which represents a generic user:

class User:

def __init__(self, name, user_id, role):

self.name = name

self.user_id = user_id

self.role = role

# Snip...

At some point, you need to add a feature that allows employees to access different components of a CRM system. Your first thought is to modify User to add the new functionality. However, that could make the class too complex, so you decide to create a subclass, CRMUser, to provide the required functionality.

The class will take a user name and CRM component as arguments. It’ll also take some **kwargs. You want to implement CRMUser in a way that allows you to provide sensible default values to the base class’s initializer without losing the flexibility of **kwargs.

Here’s how you solve the problem using ChainMap:

from collections import ChainMap

class CRMUser(User):

def __init__(self, name, component, **kwargs):

defaults = {"user_id": next(component.user_id), "role": "read"}

super().__init__(name, **ChainMap(kwargs, defaults))

In this code sample, you create a subclass of User. In the class initializer, you take name, component, and **kwargs as arguments. Then you create a local dictionary with default values for user_id and role. Then you call the parent class’s .__init__() method using super(). In this call, you pass name directly to the parent’s initializer and provide the default values to the rest of the arguments using a chain map.

Note that the ChainMap object takes kwargs and then defaults as arguments. This order guarantees that manually-provided arguments (kwargs) take precedence over defaults values when you instantiate the class.

Conclusion

Python’s ChainMap from the collections module provides an efficient tool for managing several dictionaries as a single one. This class is handy when you have multiple dictionaries representing different scopes or contexts and need to set access priorities to the underlying data.

ChainMap groups multiple dictionaries and mappings in an updatable view that works pretty much like a dictionary. You can use ChainMap objects to efficiently work with several dictionaries, define key lookup priorities, and manage multiple contexts in Python.

In this tutorial, you learned how to:

- Create

ChainMapinstances in your Python programs - Explore the differences between

ChainMapanddict - Manage several dictionaries as one using

ChainMap - Set priorities for key lookup operations with

ChainMap

In this tutorial, you also coded a few practical examples that helped you better understand when and how to use ChainMap in your Python code.