Python’s walrus operator (:=) allows you to assign values to variables as part of an expression. It can simplify your code by combining assignment and evaluation in a single statement. You use it to streamline constructs like list comprehensions, loops, and conditionals, making your code more concise and readable. The walrus operator is particularly useful when you want to avoid repetitive function calls or calculations.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand that:

- The walrus operator (

:=) is a syntax for assigning variables within expressions in Python. - Assignment expressions use the walrus operator in Python.

- You can use the walrus operator to streamline code, such as in loops or conditionals.

- Assignment expressions return the assigned value, unlike regular assignments.

- Regular assignments don’t return values to prevent unintended behavior and bugs.

Understanding the walrus operator will enhance your ability to write efficient and concise Python code, especially when dealing with complex conditions and loops.

Get Your Code: Click here to download the free sample code that shows you how to use Python’s walrus operator.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “The Walrus Operator: Python's Assignment Expressions” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

The Walrus Operator: Python's Assignment ExpressionsIn this quiz, you'll test your understanding of Python's walrus operator. This operator was introduced in Python 3.8, and understanding it can help you write more concise and efficient code.

Walrus Operator Fundamentals

First, look at some different terms that programmers use to refer to this new syntax. You’ve already seen a few in this tutorial.

The := operator is officially known as the assignment expression operator. During early discussions, it was dubbed the walrus operator because the := syntax resembles the eyes and tusks of a walrus lying on its side. You may also see the := operator referred to as the colon equals operator. Yet another term used for assignment expressions is named expressions.

Hello, Walrus!

To get a first impression of what assignment expressions are all about, start your REPL and play around with the following code:

1>>> walrus = False

2>>> walrus

3False

4

5>>> (walrus := True)

6True

7>>> walrus

8True

Line 1 shows a traditional assignment statement where the value False is assigned to walrus. Next, on line 5, you use an assignment expression to assign the value True to walrus. After both lines 1 and 5, you can refer to the assigned values by using the variable name walrus.

You might be wondering why you’re using parentheses on line 5, and you’ll learn why the parentheses are needed later on in this tutorial.

Note: A statement in Python is a unit of code. An expression is a special statement that can be evaluated to some value.

For example, 1 + 2 is an expression that evaluates to the value 3, while number = 1 + 2 is an assignment statement that doesn’t evaluate to a value. Although running the statement number = 1 + 2 doesn’t evaluate to 3, it does assign the value 3 to number.

In Python, you often see simple statements like return statements and import statements, as well as compound statements like if statements and function definitions. These are all statements, not expressions.

There’s a subtle—but important—difference between the two types of assignments with the walrus variable. An assignment expression returns the value, while a traditional assignment doesn’t. You can see this in action when the REPL doesn’t print any value after walrus = False on line 1 but prints out True after the assignment expression on line 5.

You can see another important aspect about walrus operators in this example. Though it might look new, the := operator does not do anything that isn’t possible without it. It only makes certain constructs more convenient and can sometimes communicate the intent of your code more clearly.

Now you have a basic idea of what the := operator is and what it can do. It’s an operator used in assignment expressions, which can return the value being assigned, unlike traditional assignment statements. To get deeper and really learn about the walrus operator, continue reading to see where you should and shouldn’t use it.

Implementation

Like most new features in Python, assignment expressions were introduced through a Python Enhancement Proposal (PEP). PEP 572 describes the motivation for introducing the walrus operator, the details of the syntax, and examples where the := operator can be used to improve your code.

This PEP was originally written by Chris Angelico in February 2018. Following some heated discussion, PEP 572 was accepted by Guido van Rossum in July 2018.

Since then, Guido announced that he was stepping down from his role as benevolent dictator for life (BDFL). Since early 2019, the Python language has been governed by an elected steering council instead.

The walrus operator was implemented by Emily Morehouse, and made available in the first alpha release of Python 3.8.

Motivation

In many languages, including C and its derivatives, assignment statements are also expressions. This can be both very powerful and a source of confusing bugs. For example, the following code is valid C but doesn’t execute as intended:

int x = 3, y = 8;

if (x = y) {

printf("x and y are equal (x = %d, y = %d)", x, y);

}

Here, if (x = y) will evaluate to true, and the code snippet will print out x and y are equal (x = 8, y = 8). Is this the result you were expecting? You were trying to compare x and y. How did the value of x change from 3 to 8?

The problem is that you’re using the assignment operator (=) instead of the equality comparison operator (==). In C, x = y is an expression that evaluates to the value of y. In this example, x = y is evaluated as 8, which is considered truthy in the context of the if statement.

Take a look at a corresponding example in Python. This code causes a SyntaxError:

x, y = 3, 8

if x = y:

print(f"x and y are equal ({x = }, {y = })")

Unlike the C example, this Python code gives you an explicit error instead of a bug.

The distinction between assignment statements and assignment expressions in Python is useful in order to avoid these kinds of hard-to-find bugs. PEP 572 argues that Python is better suited to having different syntax for assignment statements and expressions instead of turning the existing assignment statements into expressions.

One design principle underpinning the walrus operator is that there are no identical code contexts where both an assignment statement using the = operator and an assignment expression using the := operator would be valid. For example, you can’t do a plain assignment with the walrus operator:

>>> walrus := True

File "<stdin>", line 1

walrus := True

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

In many cases, you can add parentheses (()) around the assignment expression to make it valid Python:

>>> (walrus := True) # Valid, but regular assignments are preferred

True

Writing a traditional assignment statement with = isn’t allowed inside such parentheses. This helps you catch potential bugs.

Later on in this tutorial, you’ll learn more about situations where the walrus operator isn’t allowed, but first you’ll learn about the situations where you might want to use it.

Walrus Operator Use Cases

In this section, you’ll see several examples where the walrus operator can simplify your code. A general theme in all these examples is that you’ll avoid different kinds of repetition:

- Repeated function calls can make your code slower than necessary.

- Repeated statements can make your code hard to maintain.

- Repeated calls that exhaust iterators can make your code overly complex.

You’ll see how the walrus operator can help in each of these situations.

Debugging

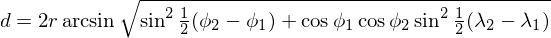

Arguably one of the best use cases for the walrus operator is when debugging complex expressions. Say that you want to find the distance between two locations along the earth’s surface. One way to do this is to use the haversine formula:

ϕ represents the latitude, and λ represents the longitude of each location. To demonstrate this formula, you can calculate the distance between Oslo (59.9°N 10.8°E) and Vancouver (49.3°N 123.1°W) as follows:

>>> from math import asin, cos, radians, sin, sqrt

>>> # Approximate radius of Earth in kilometers

>>> rad = 6371

>>> # Locations of Oslo and Vancouver

>>> ϕ1, λ1 = radians(59.9), radians(10.8)

>>> ϕ2, λ2 = radians(49.3), radians(-123.1)

>>> # Distance between Oslo and Vancouver

>>> 2 * rad * asin(

... sqrt(

... sin((ϕ2 - ϕ1) / 2) ** 2

... + cos(ϕ1) * cos(ϕ2) * sin((λ2 - λ1) / 2) ** 2

... )

... )

...

7181.7841229421165

As you can see, the distance from Oslo to Vancouver is just under 7,200 kilometers.

Note: Python source code is typically written using UTF-8 Unicode. This allows you to use Greek letters like ϕ and λ in your code, which may be useful when translating mathematical formulas. Wikipedia shows some alternatives for using Unicode on your system.

While UTF-8 is supported (in string literals, for instance), Python’s variable names use a more limited character set. For example, you can’t use emojis while naming your variables. That’s a good restriction!

Now, say that you need to double-check your implementation and want to see how much the haversine terms contribute to the final result. You could copy and paste the term from your main code to evaluate it separately. However, you could also use the := operator to give a name to the subexpression that you’re interested in:

>>> 2 * rad * asin(

... sqrt(

... (ϕ_hav := sin((ϕ2 - ϕ1) / 2) ** 2)

... + cos(ϕ1) * cos(ϕ2) * sin((λ2 - λ1) / 2) ** 2

... )

... )

...

7181.7841229421165

>>> ϕ_hav

0.008532325425222883

The advantage of using the walrus operator here is that you calculate the value of the full expression and keep track of the value of ϕ_hav at the same time. This allows you to confirm that you didn’t introduce any errors while debugging.

Lists and Dictionaries

Lists are powerful data structures in Python that often represent a series of related attributes. Similarly, dictionaries are used all over Python and are great for structuring information.

Sometimes when setting up these data structures, you end up performing the same operation several times. As a first example, calculate some basic descriptive statistics of a list of numbers and store them in a dictionary:

>>> numbers = [2, 8, 0, 1, 1, 9, 7, 7]

>>> description = {

... "length": len(numbers),

... "sum": sum(numbers),

... "mean": sum(numbers) / len(numbers),

... }

>>> description

{'length': 8, 'sum': 35, 'mean': 4.375}

Note that both the sum and the length of the numbers list are calculated twice. The consequences are not too bad in this simple example, but if the list were larger or the calculations were more complicated, you might want to optimize the code. To do this, you can first move the function calls out of the dictionary definition:

>>> numbers = [2, 8, 0, 1, 1, 9, 7, 7]

>>> num_length = len(numbers)

>>> num_sum = sum(numbers)

>>> description = {

... "length": num_length,

... "sum": num_sum,

... "mean": num_sum / num_length,

... }

>>> description

{'length': 8, 'sum': 35, 'mean': 4.375}

The variables num_length and num_sum are only used to optimize the calculations inside the dictionary. By using the walrus operator, you can make this role clearer:

>>> numbers = [2, 8, 0, 1, 1, 9, 7, 7]

>>> description = {

... "length": (num_length := len(numbers)),

... "sum": (num_sum := sum(numbers)),

... "mean": num_sum / num_length,

... }

>>> description

{'length': 8, 'sum': 35, 'mean': 4.375}

You’ve now defined num_length and num_sum inside the definition of description. This is a clear hint to anybody reading this code that these variables are just used to optimize these calculations and aren’t used again later.

Note: The scope of the num_length and num_sum variables is the same in the example with the walrus operator and in the example without. This means that in both examples, the variables are available after the definition of description.

Even though both examples are very similar functionally, a benefit of using the assignment expressions is that the := operator communicates the intent of these variables as throwaway optimizations.

In the next example, you’ll work with a bare-bones implementation of the wc utility for counting lines, words, and characters in a text file:

wc.py

1import pathlib

2import sys

3

4for filename in sys.argv[1:]:

5 path = pathlib.Path(filename)

6 counts = (

7 path.read_text().count("\n"), # Number of lines

8 len(path.read_text().split()), # Number of words

9 len(path.read_text()), # Number of characters

10 )

11 print(*counts, path)

This script can read one or several text files and report how many lines, words, and characters each of them contains. Here’s a breakdown of what’s happening in the code:

- Line 4 loops over each filename provided by the user. The

sys.argvlist contains each argument given on the command line, starting with the name of your script. For more information aboutsys.argv, you can check out Python Command Line Arguments. - Line 5 converts each filename string to a

pathlib.Pathobject. Storing a filename in aPathobject allows you to conveniently read the text file in the next lines. - Lines 6 to 10 construct a tuple of counts to represent the number of lines, words, and characters in one text file.

- Line 7 reads a text file and calculates the number of lines by counting newlines.

- Line 8 reads a text file and calculates the number of words by splitting on whitespace.

- Line 9 reads a text file and calculates the number of characters by finding the length of the string.

- Line 11 prints all three counts together with the filename to the console. The

*countssyntax unpacks thecountstuple. In this case, theprint()statement is equivalent toprint(counts[0], counts[1], counts[2], path).

To see wc.py in action, you can use the script on itself as follows:

$ python wc.py wc.py

11 32 307 wc.py

In other words, the wc.py file consists of 11 lines, 32 words, and 307 characters.

If you look closely at this implementation, then you’ll notice that it’s far from optimal. In particular, it repeats the call to path.read_text() three times. That means that the program reads each text file three times. You can use the walrus operator to avoid the repetition:

wc.py

import pathlib

import sys

for filename in sys.argv[1:]:

path = pathlib.Path(filename)

counts = (

(text := path.read_text()).count("\n"), # Number of lines

len(text.split()), # Number of words

len(text), # Number of characters

)

print(*counts, path)

You assign the contents of the file to text, which you reuse in the next two calculations. Note the placement of parentheses that help scope that text will refer to the text in the file and not the number of lines.

The program still functions the same, although the word and character counts have changed:

$ python wc.py wc.py

11 34 293 wc.py

As in the earlier examples, an alternative approach is to define text before the definition of counts:

wc.py

import pathlib

import sys

for filename in sys.argv[1:]:

path = pathlib.Path(filename)

text = path.read_text()

counts = (

text.count("\n"), # Number of lines

len(text.split()), # Number of words

len(text), # Number of characters

)

print(*counts, path)

While this is one line longer than the previous implementation, it probably provides the best balance between readability and efficiency. The := assignment expression operator isn’t always the most readable solution even when it makes your code more concise.

List Comprehensions

List comprehensions are great for constructing and filtering lists. They clearly state the intent of the code and will usually run quite fast.

There’s one list comprehension use case where the walrus operator can be particularly useful. Say that you want to apply some computationally expensive function, slow(), to the elements in your list and filter on the resulting values. You could do something like the following:

slow_calculations.py

numbers = [7, 6, 1, 4, 1, 8, 0, 6]

results = [slow(num) for num in numbers if slow(num) > 0]

Here, you filter the numbers list and leave the positive results from applying slow(). The problem with this code is that this expensive function is called twice.

A very common solution for this type of situation is rewriting your code to use an explicit for loop:

slow_calculations.py

results = []

for num in numbers:

value = slow(num)

if value > 0:

results.append(value)

This will only call slow() once. Unfortunately, the code is now more verbose, and the intent of the code is harder to understand. The list comprehension had clearly signaled that you were creating a new list, while this is more hidden in the explicit for loop since several lines of code separate the list creation and the use of .append(). Additionally, a list comprehension runs faster than the repeated calls to .append().

You can code some other solutions by using a filter() expression or a kind of double list comprehension:

slow_calculations.py

# Using filter

results = filter(lambda value: value > 0, (slow(num) for num in numbers))

# Using a double list comprehension

results = [value for num in numbers for value in [slow(num)] if value > 0]

The good news is that there’s only one call to slow() for each number. The bad news is that the code’s readability has suffered in both expressions.

Figuring out what’s actually happening in the double list comprehension takes a fair amount of head-scratching. Essentially, the second for statement is used only to give the name value to the return value of slow(num). Fortunately, that sounds like something that you can accomplish with an assignment expression!

You can rewrite the list comprehension using the walrus operator as follows:

slow_calculations.py

results = [value for num in numbers if (value := slow(num)) > 0]

Note that the parentheses around value := slow(num) are required. This version is effective and readable, and it communicates the intent of the code well.

Note: You need to add the assignment expression on the if clause of the list comprehension. If you try to define value with the other call to slow(), then it won’t work:

>>> results = [(value := slow(num)) for num in numbers if value > 0]

NameError: name 'value' is not defined

This will raise a NameError because the if clause is evaluated before the expression at the beginning of the comprehension.

Next, look at a slightly more involved and practical example. Say that you want to use the Real Python feed to find the titles of the last episodes of the Real Python Podcast.

You can use the Real Python Feed Reader to download information about the latest Real Python publications. In order to find the podcast episode titles, you’ll use the third-party Parse package. Start by creating a virtual environment and installing both packages:

(venv) $ python -m pip install realpython-reader parse

You can now read the latest titles published by Real Python:

>>> from reader import feed

>>> feed.get_titles()

['The Walrus Operator: Python's Assignment Expressions',

'Python News Roundup: August 2024',

'The Real Python Podcast – Episode #216: The Black Python Devs Community',

'Asynchronous Iterators and Iterables in Python',

...]

Podcast titles start with "The Real Python Podcast", so here you can create a pattern that Parse can use to identify them:

>>> import parse

>>> pattern = parse.compile(

... "The Real Python Podcast – Episode #{num:d}: {name}"

... )

Compiling the pattern beforehand speeds up later comparisons, especially when you want to match the same pattern over and over. You can check if a string matches your pattern using either pattern.parse() or pattern.search():

>>> pattern.parse(

... "The Real Python Podcast – Episode #216: "

... "The Black Python Devs Community"

... )

...

<Result () {'num': 216, 'name': 'The Black Python Devs Community'}>

Note that Parse is able to pick out the podcast episode number and the episode name. The episode number is converted to an integer data type because you used the :d format specifier.

Time to get back to the task at hand. In order to list all the recent podcast titles, you need to check whether each string matches your pattern and then parse out the episode title. A first attempt may look something like this:

>>> import parse

>>> from reader import feed

>>> pattern = parse.compile(

... "The Real Python Podcast – Episode #{num:d}: {name}"

... )

>>> podcasts = [

... pattern.parse(title)["name"]

... for title in feed.get_titles()

... if pattern.parse(title)

... ]

>>> podcasts[:3]

['The Black Python Devs Community',

'Using GraphQL in Django With Strawberry & Prototype Purgatory',

'Build Captivating Display Tables in Python With Great Tables']

Though it works, you might notice the same problem you saw earlier. You’re parsing each title twice because you filter out titles that match your pattern and then use that same pattern to pick out the episode title.

Like you did earlier, you can avoid the double work by rewriting the list comprehension using either an explicit for loop or a double list comprehension. Using the walrus operator, however, is even more straightforward:

>>> podcasts = [

... podcast["name"]

... for title in feed.get_titles()

... if (podcast := pattern.parse(title))

... ]

Assignment expressions work well to simplify these kinds of list comprehensions. They keep your code readable and save you from doing a potentially expensive operation twice.

Note: The Real Python Podcast has its own separate RSS feed, which you should use if you want to play around with information about the podcast only. You can get all the episode titles with the following code:

>>> from reader import feed

>>> podcasts = feed.get_titles("https://realpython.com/podcasts/rpp/feed")

See The Real Python Podcast for options to listen to it using your podcast player.

In this section, you’ve focused on examples where you can rewrite list comprehensions using the walrus operator. The same principles also apply if you see that you need to repeat an operation in a dictionary comprehension, a set comprehension, or a generator expression.

The following example uses a generator expression to calculate the average length of episode titles that are over 50 characters long:

>>> import statistics

>>> statistics.mean(

... title_length

... for title in podcasts

... if (title_length := len(title)) > 50

... )

61.525

The generator expression uses an assignment expression to avoid calculating the length of each episode title twice.

While Loops

Python has two different loop constructs: for loops and while loops. You typically use a for loop when you need to iterate over a known sequence of elements. A while loop, on the other hand, is for when you don’t know beforehand how many times you’ll need to repeat the loop.

In while loops, you need to define and check the ending condition at the top of the loop. This sometimes leads to some awkward code when you need to do some setup before performing the check. Here’s a snippet from a multiple-choice quiz program that asks the user to answer a question with one of several valid answers:

walrus_quiz.py

question = "Do you use the walrus operator?"

valid_answers = {"yes", "Yes", "y", "Y", "no", "No", "n", "N"}

user_answer = input(f"\n{question} ")

while user_answer not in valid_answers:

print(f"Please answer one of {', '.join(valid_answers)}")

user_answer = input(f"\n{question} ")

This works but has an unfortunate repetition of two identical input() lines. It’s necessary to get at least one answer from the user before checking whether it’s valid or not. You then have a second call to input() inside the while loop to ask for a second answer in case the original user_answer wasn’t valid.

If you want to make your code more maintainable, it’s quite common to rewrite this kind of logic with a while True loop. Instead of making the check part of the main while statement, the check is performed later in the loop together with an explicit break:

walrus_quiz.py

# ...

while True:

user_answer = input(f"\n{question} ")

if user_answer in valid_answers:

break

print(f"Please answer one of {', '.join(valid_answers)}")

This has the advantage of avoiding the repetition. However, the actual check is now harder to spot.

Assignment expressions can simplify these kinds of loops. In this example, you can now put the check back together with while where it makes more sense:

walrus_quiz.py

# ...

while (user_answer := input(f"\n{question} ")) not in valid_answers:

print(f"Please answer one of {', '.join(valid_answers)}")

The while statement is a bit denser, but the code now communicates the intent more clearly without repeated lines or seemingly infinite loops.

You can expand the box below to see the full code of the multiple-choice quiz program and try a couple of questions about the walrus operator yourself.

This script runs a multiple-choice quiz. You’ll be asked each of the questions in order, but the order of answers will be shuffled each time:

walrus_quiz.py

import random

import string

QUESTIONS = {

"What is the formal name of PEP 572?": [

"Assignment Expressions",

"Named Expressions",

"The Walrus Operator",

"The Colon Equals Operator",

],

"Which one of these is an invalid use of the walrus operator?": [

"[y**2 for x in range(10) if y := f(x) > 0]",

"print(y := f(x))",

"(y := f(x))",

"any((y := f(x)) for x in range(10))",

],

}

num_correct = 0

for question, answers in QUESTIONS.items():

correct = answers[0]

random.shuffle(answers)

coded_answers = dict(zip(string.ascii_lowercase, answers))

valid_answers = sorted(coded_answers.keys())

for code, answer in coded_answers.items():

print(f" {code}) {answer}")

while (user_answer := input(f"\n{question} ")) not in valid_answers:

print(f"Please answer one of {', '.join(valid_answers)}")

if coded_answers[user_answer] == correct:

print(f"Correct, the answer is {user_answer!r}\n")

num_correct += 1

else:

print(f"No, the answer is {correct!r}\n")

print(f"You got {num_correct} correct out of {len(QUESTIONS)} questions")

Note that the first answer is assumed to be the correct one, while the others serve as distractors. You can add more questions to the quiz yourself. Feel free to share your questions with the community in the comments section below the tutorial!

See Build a Quiz Application With Python if you want to dive deeper into using Python to quiz yourself or your friends. You can also quiz yourself on your knowledge of the walrus operator:

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “The Walrus Operator: Python's Assignment Expressions” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

The Walrus Operator: Python's Assignment ExpressionsIn this quiz, you'll test your understanding of Python's walrus operator. This operator was introduced in Python 3.8, and understanding it can help you write more concise and efficient code.

You can often simplify while loops by using assignment expressions. The original PEP shows an example from the standard library that makes the same point.

Witnesses and Counterexamples

In the examples you’ve seen so far, the := assignment expression operator does essentially the same job as the = assignment operator in your old code. You’ve seen how to simplify code, and now you’ll learn about a different type of use case that this operator makes possible.

In this section, you’ll learn how you can find witnesses when calling any() by using a clever trick that isn’t immediately possible without using the walrus operator. A witness, in this context, is an element that satisfies the check and causes any() to return True.

By applying similar logic, you’ll also learn how you can find counterexamples when working with all(). A counterexample, in this context, is an element that doesn’t satisfy the check and causes all() to return False.

In order to have some data to work with, define the following list of city names:

>>> cities = ["Vancouver", "Oslo", "Berlin", "Krakow", "Graz", "Belgrade"]

You can use any() and all() to answer questions about your data:

>>> # Does ANY city name start with "B"?

>>> any(city.startswith("B") for city in cities)

True

>>> # Does ANY city name have at least 10 characters?

>>> any(len(city) >= 10 for city in cities)

False

>>> # Do ALL city names contain "A" or "L"?

>>> all(set(city.lower()) & set("al") for city in cities)

True

>>> # Do ALL city names start with "B"?

>>> all(city.startswith("B") for city in cities)

False

In each of these cases, any() and all() give you plain True or False answers. What if you’re also interested in seeing an example or a counterexample of the city names? It could be nice to see what’s causing your True or False result:

-

Does any city name start with

"B"?Yes, because

"Berlin"starts with"B". -

Do all city names start with

"B"?No, because

"Oslo"doesn’t start with"B".

In other words, you want a witness or a counterexample to justify the answer.

Capturing a witness to an any() expression has not been intuitive in earlier versions of Python. If you were calling any() on a list and then realized you also wanted a witness, you’d typically need to rewrite your code:

>>> witnesses = [city for city in cities if city.startswith("B")]

>>> if witnesses:

... print(f"{witnesses[0]} starts with B")

... else:

... print("No city name starts with B")

...

Berlin starts with B

Here, you first capture all city names that start with "B". Then, if there’s at least one such city name, you print out the first city name starting with "B". Note that here you’re actually not using any() even though you’re doing a similar operation with the list comprehension.

By using the := operator, you can find witnesses directly in your any() expressions:

>>> if any((witness := city).startswith("B") for city in cities):

... print(f"{witness} starts with B")

... else:

... print("No city name starts with B")

...

Berlin starts with B

You can capture a witness inside the any() expression. The reason this works is a bit subtle and relies on any() and all() using short-circuit evaluation: they only check as many items as necessary to determine the result.

Note: If you want to check whether all city names start with the letter "B", then you can look for a counterexample by replacing any() with all() and updating the print() functions to report the first item that doesn’t pass the check.

You can more clearly see what’s happening by wrapping .startswith("B") in a function that also prints out which item is being checked:

>>> def starts_with_b(name):

... print(f"Checking {name}: {(result := name.startswith('B'))}")

... return result

...

>>> any(starts_with_b(city) for city in cities)

Checking Vancouver: False

Checking Oslo: False

Checking Berlin: True

True

Note that any() doesn’t actually check all the items in cities. It only checks items until it finds one that satisfies the condition. Combining the := operator and any() works by iteratively assigning each item that is being checked to witness. However, only the last such item survives and shows which item was last checked by any().

Even when any() returns False, a witness is found:

>>> any(len(witness := city) >= 10 for city in cities)

False

>>> witness

'Belgrade'

However, in this case, witness doesn’t give any insight. 'Belgrade' doesn’t contain ten or more characters. The witness only shows which item happened to be evaluated last.

Walrus Operator Syntax

One of the main reasons assignments weren’t expressions in Python from the beginning is that the visual similarity of the assignment operator (=) and the equality comparison operator (==) could potentially lead to bugs.

When introducing assignment expressions, the developers put a lot of thought into how to avoid similar bugs with the walrus operator. As mentioned earlier, one important feature is that the := operator is never allowed as a direct replacement for the = operator, and vice versa.

As you saw at the beginning of this tutorial, you can’t use a plain assignment expression to assign a value:

>>> walrus := True

File "<stdin>", line 1

walrus := True

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

It’s syntactically legal to use an assignment expression to only assign a value, but you need to add parentheses:

>>> (walrus := True)

True

Even though it’s possible, this is a prime example of where you should stay away from the walrus operator and use a traditional assignment statement instead.

PEP 572 shows several other examples where the := operator is either illegal or discouraged. The following examples all cause a SyntaxError:

>>> lat = lon := 0

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> angle(phi = lat := 59.9)

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> def distance(phi = lat := 0, lam = lon := 0):

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

In all these cases, you’re better served using = instead. The next examples are similar and are all legal code. However, the walrus operator doesn’t improve your code in any of these cases:

>>> lat = (lon := 0) # Discouraged

>>> angle(phi = (lat := 59.9)) # Discouraged

>>> def distance(phi = (lat := 0), lam = (lon := 0)): # Discouraged

... pass

...

None of these examples make your code more readable. You should instead do the extra assignment separately by using a traditional assignment statement. See PEP 572 for more details about the reasoning.

There’s one use case where the := character sequence is already valid Python. In f-strings, you use a colon (:) to separate values from their format specification. For example:

>>> x = 3

>>> f"{x:=8}"

' 3'

The := in this case does look like a walrus operator, but the effect is quite different. To interpret x:=8 inside the f-string, the expression is broken into three parts: x, :, and =8.

Here, x is the value, : acts as a separator, and =8 is a format specification. According to Python’s Format Specification Mini-Language, in this context = specifies an alignment option. In this case, the value is padded with spaces in a field of width 8.

To use assignment expressions inside f-strings, you need to add parentheses:

>>> x = 3

>>> f"{(x := 8)}"

'8'

>>> x

8

This updates the value of x as expected. However, you’re probably better off using traditional assignments outside of your f-strings instead.

Now, look at some other situations where assignment expressions are illegal:

-

Attribute and item assignment: You can only assign to simple names, not dotted or indexed names:

Python>>> (mapping["hearts"] := "♥") SyntaxError: cannot use assignment expressions with subscript >>> (number.answer := 42) SyntaxError: cannot use assignment expressions with attributeThis fails with a descriptive error message. There’s no straightforward workaround.

-

Iterable unpacking: You can’t unpack when using the walrus operator:

Python>>> lat, lon := 59.9, 10.8 SyntaxError: invalid syntaxIf you add parentheses around the whole expression, then Python will interpret it as a 3-tuple with the three elements

lat,59.9, and10.8. -

Augmented assignment: You can’t use the walrus operator combined with augmented assignment operators like

+=. This raises aSyntaxError:Python>>> count +:= 1 SyntaxError: invalid syntaxThe easiest workaround would be to do the augmentation explicitly. You could, for example, do

(count := count + 1). PEP 577 originally described how to add augmented assignment expressions to Python, but the proposal was withdrawn.

When you’re using the walrus operator, it’ll behave similarly to traditional assignment statements in many respects:

-

The scope of the assignment target is the same as for assignments. It’ll follow the LEGB rule. Typically, the assignment will happen in the local scope, but if the target name is already declared

globalornonlocal, that declaration is honored. -

The precedence of the walrus operator can cause some confusion. It binds less tightly than all other operators except the comma, so you might need parentheses to delimit the expression that you’re assigning. As an example, note what happens when you don’t use parentheses:

Python>>> number = 3 >>> if square := number ** 2 > 5: ... print(square) ... Truesquareis bound to the whole expressionnumber ** 2 > 5. In other words,squaregets the valueTrueand not the value ofnumber ** 2, which was the intention. In this case, you can delimit the expression with parentheses:Python>>> number = 3 >>> if (square := number ** 2) > 5: ... print(square) ... 9The parentheses make the

ifstatement both clearer and actually correct.There’s one final gotcha. When assigning a tuple using the walrus operator, you always need to use parentheses around the tuple. Compare the following assignments:

Python>>> walrus = 3.7, False >>> walrus (3.7, False) >>> (walrus := 3.8, True) (3.8, True) >>> walrus 3.8 >>> (walrus := (3.8, True)) (3.8, True) >>> walrus (3.8, True)Note that in the second example,

walrustakes the value3.8and not the whole tuple3.8, True. That’s because the:=operator binds more tightly than the comma. This may seem a bit annoying. However, if the:=operator bound less tightly than the comma, then it wouldn’t be possible to use the walrus operator in function calls with more than one argument. -

The style recommendations for the walrus operator are mostly the same as for the

=operator used for assignment. First, always add spaces around the:=operator in your code. Second, use parentheses around the expression as necessary, but avoid adding extra parentheses that you don’t need.

The general design of assignment expressions is to make them easy to use when they’re helpful but to avoid overusing them when they might clutter up your code.

Walrus Operator Pitfalls

The walrus operator is a newer syntax that’s only available in Python 3.8 and later. This means that any code you write that uses the := syntax will only work on these versions of Python.

If you need to support legacy versions of Python, then you can’t ship code that uses assignment expressions. As you’ve learned in this tutorial, you can always write code without the walrus operator and stay compatible with older versions.

Experience with the walrus operator indicates that := will not revolutionize Python. Instead, using assignment expressions where they’re useful can help you make several small improvements to your code that could benefit your work overall.

You’ll run into several situations where it’s possible for you to use the walrus operator, but it won’t necessarily improve the readability or efficiency of your code. In those cases, you’re better off writing your code in a more traditional manner.

Conclusion

You now know how the walrus operator works and how you can use it in your own code. By using the := syntax, you can avoid different kinds of repetition in your code and make your code both more efficient and easier to read and maintain. At the same time, you shouldn’t use assignment expressions everywhere. They’ll only help you in specific use cases.

In this tutorial, you learned how to:

- Identify the walrus operator and understand its meaning

- Understand use cases for the walrus operator

- Avoid repetitive code by using the walrus operator

- Convert between code using the walrus operator and code using other assignment methods

- Use appropriate style in your assignment expressions

To learn more about the details of assignment expressions, see PEP 572. You can also check out the PyCon 2019 talk PEP 572: The Walrus Operator, where Dustin Ingram gives an overview of both the walrus operator and the discussion around the PEP.

Get Your Code: Click here to download the free sample code that shows you how to use Python’s walrus operator.

Frequently Asked Questions

Now that you have some experience with the walrus operator in Python, you can use the questions and answers below to check your understanding and recap what you’ve learned.

These FAQs are related to the most important concepts you’ve covered in this tutorial. Click the Show/Hide toggle beside each question to reveal the answer.

The walrus operator (:=) is an operator that allows you to assign values to variables as part of an expression.

Yes. Or more correctly, the walrus operator is another term for an assignment expression operator, which lets you assign values within an assignment expression.

You use the walrus operator when you want to simplify your code by reducing repetition, particularly in loops, list comprehensions, and conditional expressions.

Assignment expressions return the value being assigned, allowing you to use them within expressions, while regular assignments don’t return a value.

Use the walrus operator to make your code more concise and readable, but avoid overusing it when traditional assignments are clearer and more appropriate.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “The Walrus Operator: Python's Assignment Expressions” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Interactive Quiz

The Walrus Operator: Python's Assignment ExpressionsIn this quiz, you'll test your understanding of Python's walrus operator. This operator was introduced in Python 3.8, and understanding it can help you write more concise and efficient code.