If you’re serious about web development, then you’ll need to learn about JavaScript at some point. Year after year, numerous surveys have shown that JavaScript is one of the most popular programming languages in the world, with a large and growing community of developers. Just like Python, modern JavaScript can be used almost anywhere, including the front end, back end, desktop, mobile, and the Internet of Things (IoT). Sometimes it might not be an obvious choice between Python vs JavaScript.

If you’ve never used JavaScript before or have felt overwhelmed by the quick pace of its evolution in recent years, then this article will set you on the right path. You should already know the basics of Python to benefit fully from the comparisons made between the two languages.

In this article, you’ll learn how to:

- Compare Python vs JavaScript

- Choose the right language for the job

- Write a shell script in JavaScript

- Generate dynamic content on a web page

- Take advantage of the JavaScript ecosystem

- Avoid common pitfalls in JavaScript

Free Bonus: 5 Thoughts On Python Mastery, a free course for Python developers that shows you the roadmap and the mindset you’ll need to take your Python skills to the next level.

JavaScript at a Glance

If you’re already familiar with the origins of JavaScript or just want to see the code in action, then feel free to jump ahead to the next section. Otherwise, prepare for a brief history lesson that will take you through the evolution of JavaScript.

It’s Not Java!

Many people, notably some IT recruiters, believe that JavaScript and Java are the same language. It’s hard to blame them, though, because inventing such a familiar-sounding name was a marketing trick.

JavaScript was originally called Mocha before it was renamed to LiveScript and finally rebranded as JavaScript shortly before its release. At the time, Java was a promising web technology, but it was too difficult for nontechnical webmasters. JavaScript was intended as a somewhat similar but beginner-friendly language to supplement Java applets in web browsers.

Fun Fact: Both Java and JavaScript were released in 1995. Python was already five years old.

To add to the confusion, Microsoft developed its own version of the language, which it called JScript due to a lack of licensing rights, for use with Internet Explorer 3.0. Today, people often refer to JavaScript as JS.

While Java and JavaScript share a few similarities in their C-like syntax as well as in their standard libraries, they’re used for different purposes. Java diverged from the client side into a more general-purpose language. JavaScript, despite its simplicity, was sufficient for validating HTML forms and adding little animations.

It’s ECMAScript

JavaScript was developed in the early days of the Web by a relatively small company known as Netscape. To win the market against Microsoft and mitigate the differences across web browsers, Netscape needed to standardize their language. After being turned down by the international World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), they asked a European standardization body called ECMA (today Ecma International) for help.

ECMA defined a formal specification for the language called ECMAScript because the name JavaScript had been trademarked by Sun Microsystems. JavaScript became one of the implementations of the specification that it originally inspired.

Note: In other words, JavaScript conforms to the ECMAScript specification. Another notable member of the ECMAScript family is ActionScript, which is used on the Flash platform.

While individual implementations of the specification complied with ECMAScript to some extent, they also shipped with additional proprietary APIs. This led to web pages not displaying correctly across different browsers and the advent of libraries such as jQuery.

Are There Other Scripts?

To this day, JavaScript remains the only programming language natively supported by web browsers. It’s the lingua franca of the Web. Some people love it, while others don’t.

There have been—and continue to be—many attempts to replace or supplant JavaScript with other technologies, including:

- Rich Internet Applications: Flash, Silverlight, JavaFX

- Transpilers: Haxe, Google Web Toolkit, pyjs

- JavaScript dialects: CoffeeScript, TypeScript

These attempts were driven not only by personal preference but also by web browsers’ limitations before HTML5 came onto the scene. In those days, you couldn’t use JavaScript for computationally intensive tasks such as drawing vector graphics or processing audio.

Rich Internet Applications (RIA), on the other hand, offered an immersive desktop-like experience in the browser through plugins. They were great for games and processing media. Unfortunately, most of them were closed source. Some had security vulnerabilities or performance issues on certain platforms. To top it off, they all severely limited the ability of web search engines to index pages built with these plugins.

Around the same time came transpilers, which allowed for an automated translation of other languages into JavaScript. This made the entry barrier to front-end development much lower because suddenly back-end engineers could leverage their skills in a new field. However, the downsides were slower development time, limited support for web standards, and cumbersome debugging of the transpiled JavaScript code. To link it back to the original code, you’d need a source map.

Note: While a compiler translates human-readable code written in a high-level programming language straight into machine code, a transpiler translates one high-level language into another. That’s why transpilers are also known as source-to-source compilers. They’re not the same as cross compilers, though, which produce machine code for foreign hardware platforms.

To write Python code for the browser, you can use one of the available transpilers, such as Transcrypt or pyjs. The latter is a port of Google Web Toolkit (GWT), which was a wildly popular Java-to-JavaScript transpiler. Another option is to use a tool like Brython, which runs a streamlined version of the Python interpreter in pure JavaScript. However, the benefits might be offset by poor performance and lack of compatibility.

Transpiling allowed a ton of new languages to emerge with the intent of replacing JavaScript and addressing its shortcomings. Some of these languages were closely related dialects of JavaScript. Perhaps the first was CoffeeScript, which was created about a decade ago. One of the latest was Google’s Dart, which was the fastest-growing language in 2019 according to GitHub. Many more languages followed, but most of them are now obsolete due to the recent advances in JavaScript.

One glaring exception is Microsoft’s TypeScript, which has gained much popularity in recent years. It’s a fully compatible superset of JavaScript that adds optional static type checking. If that sounds familiar to you, that’s because Python’s type hinting was inspired by TypeScript.

While modern JavaScript is mature and actively developed, transpiling is still a common approach to ensure backward compatibility with older browsers. Even if you’re not using TypeScript, which seems to be the language of choice for many new projects, you’re still going to need to transpile your shiny new JavaScript into an older version of the language. Otherwise, you run the risk of getting a runtime error.

Some transpilers also synthesize cutting-edge web APIs, which might be unavailable on certain browsers, with a so-called polyfill.

Today, JavaScript can be thought of as the assembly language of the Web. Many professional front-end engineers tend not to write it by hand anymore. In such a case, it’s generated from scratch through transpiling.

However, even handwritten code often gets processed in some way. For example, minification removes whitespace and renames variables to reduce the amount of data to transfer and to obfuscate the code so that it’s harder to reverse engineer. This is analogous to compiling the source code of a high-level programming language into native machine code.

In addition to this, it’s worthwhile to mention that contemporary browsers support the WebAssembly standard, which is a fairly new technology. It defines a binary format for code that can run with almost-native performance in the browser. It’s fast, portable, secure, and allows for cross compilation of code written in languages like C++ or Rust. With it, for example, you could take the decades-old code of your favorite video game and run it in the browser.

At the moment, WebAssembly helps you optimize the performance of computationally critical parts of your code, but it comes with a price tag. To begin with, you need to know one of the currently supported programming languages. You have to become familiar with low-level concepts such as memory management as there’s no garbage collector yet. The integration with JavaScript code is difficult and costly. Also, there’s no easy way to call web APIs from it.

Note: For a deep dive into WebAssembly, check out The Real Python Podcast - Episode 154 with Brett Cannon.

It seems that, after all these years, JavaScript isn’t going away anytime soon.

JavaScript Starter Kit

One of the first similarities you’ll notice when comparing Python vs JavaScript is that the entry barriers for both are pretty low, making both languages very attractive to beginners who’d like to learn to code. For JavaScript, the only starting requirement is having a web browser. If you’re reading this, then you’ve already got that covered. This accessibility contributes to the language’s popularity.

The Address Bar

To get a taste of what it’s like to write JavaScript code, you can stop reading now and type the following text into the address bar before navigating to it:

The literal text is javascript:alert('hello world'), but don’t just copy and paste it!

That part after the javascript: prefix is a piece of JavaScript code. When confirmed, it should make your browser display a dialog box with the hello world message in it. Each browser renders this dialog slightly differently. For example, Google Chrome displays it like this:

Copying and pasting such a snippet into the address bar will fail in most browsers, which filter out the javascript: prefix as a safety measure against injecting malicious code.

Some browsers, such as Mozilla Firefox, take it one step further by blocking this kind of code execution entirely. In any case, this isn’t the most convenient way of working with JavaScript because you’re constrained to only one line and limited to a certain number of characters. There’s a better way.

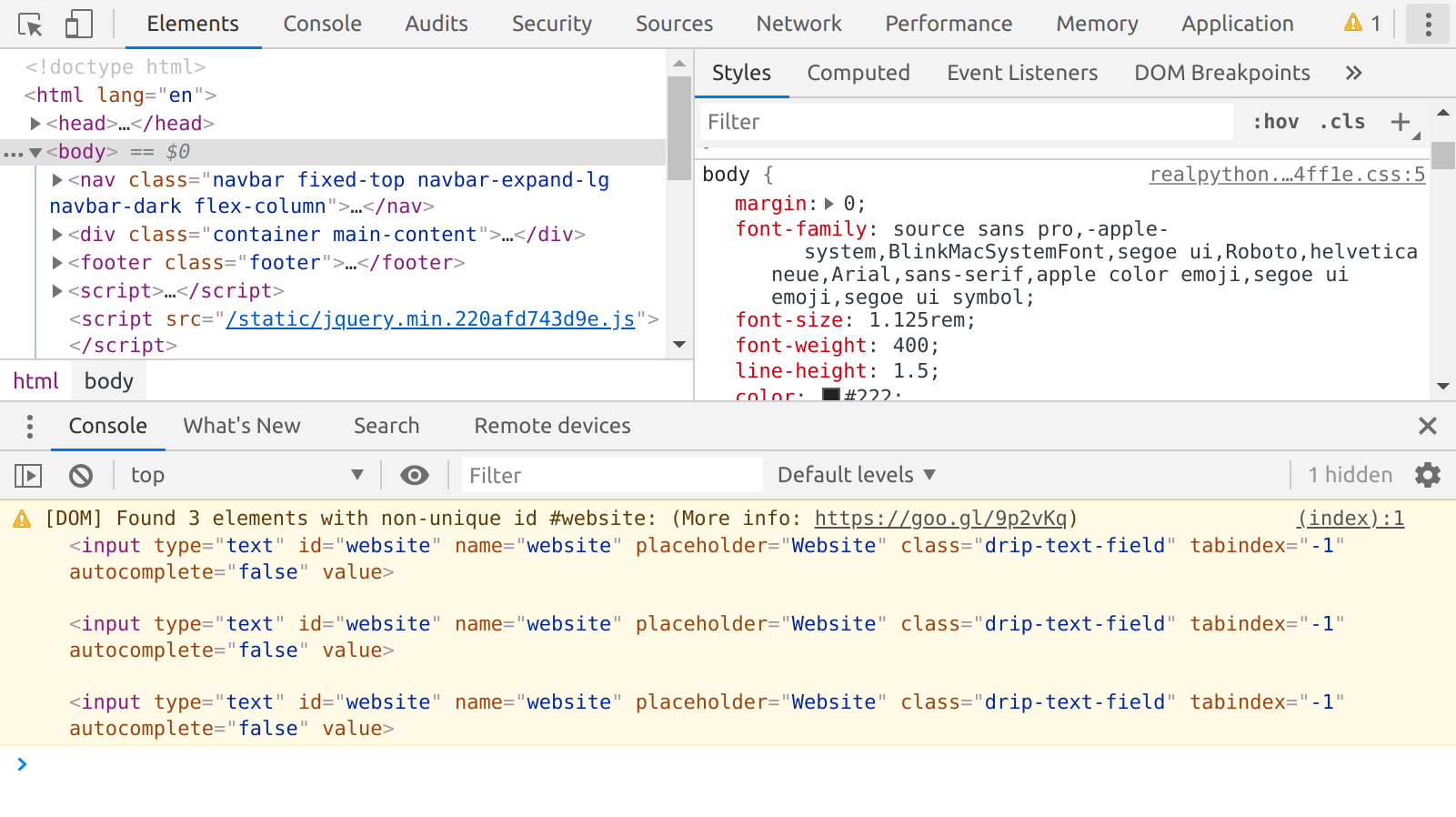

Web Developer Tools

If you’re viewing this page on a desktop or a laptop computer, then you can take advantage of the web developer tools, which provide comparable experience across competing web browsers.

Note: The examples that follow use Google Chrome version 80.0. Keyboard shortcuts may vary for other browsers, but the interface should be largely the same.

To toggle these tools, refer to your browser’s documentation or try one of these common keyboard shortcuts:

-

F12

-

Ctrl+Shift+I

-

Cmd+Option+I

This feature may be disabled by default if you’re using Apple Safari or Microsoft Edge, for example. Once the web developer tools are activated, you’ll see a myriad of tabs and toolbars with content similar to this:

Collectively, it’s a powerful development environment equipped with a JavaScript debugger, a performance and memory profiler, a network traffic manager, and much, much more. There’s even a remote debugger for physical devices connected over a USB cable!

For the moment, however, just focus on the console, which you can access by clicking a tab located at the top. Alternatively, you can quickly bring it to the front by pressing Esc at any time while using the web developer tools.

The console is primarily used for inspecting log messages emitted by the current web page, but it can also be a great JavaScript learning aid. Just like with the interactive Python interpreter, you can type JavaScript code directly into the console to have it executed on the fly:

It has everything you’d expect from a typical REPL tool and more. In particular, the console comes with syntax highlighting, contextual autocomplete, command history, line editing similar to GNU Readline, and the ability to render interactive elements. Its rendering abilities can be especially useful for introspecting objects and tabular data, jumping to source code from a stack trace, or viewing HTML elements.

You can log custom messages to the console using a predefined console object. JavaScript’s console.log() is the equivalent of Python’s print():

console.log('hello world');

This will make the message appear in the console tab in the web developer tools. Apart from that, there are a few more useful methods available in the console object.

HTML Document

By far the most natural place for the JavaScript code is somewhere near an HTML document, which it typically manipulates. You’ll learn more on that later. You can reference JavaScript from HTML in three different ways:

| Method | Code Example |

|---|---|

| HTML Element’s Attribute | <button onclick="alert('hello');">Click</button> |

HTML <script> Tag |

<script>alert('hello');</script> |

| External File | <script src="/path/to/file.js"></script> |

You can have as many of these as you like. The first and second methods embed inline JavaScript directly within an HTML document. While this is convenient, you should try to keep imperative JavaScript separate from declarative HTML to promote readability.

It’s more common to find one or more <script> tags referencing external files with JavaScript code. These files can be served by either a local or a remote web server.

The <script> tag can appear anywhere in the document as long as it’s nested in either the <head> or the <body> tag:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Home Page</title>

<script src="https://server.com/library.js"></script>

<script src="local/assets/app.js"></script>

<script>

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

</script>

</head>

<body>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet (...)</p>

<script>

console.log(add(2, 3));

</script>

</body>

</html>

What’s important is how web browsers process HTML documents. A document is read top to bottom. Whenever a <script> tag is found, it gets immediately executed even before the page has been fully loaded. If your script tries to find HTML elements that haven’t been rendered yet, then you’ll get an error.

To be safe, always put the <script> tags at the bottom of your document body:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Home Page</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet (...)</p>

<script src="https://server.com/library.js"></script>

<script src="local/assets/app.js"></script>

<script>

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

</script>

<script>

console.log(add(2, 3));

</script>

</body>

</html>

Not only will this protect you against the said error, but it will also improve the overall user experience. By moving those tags down, you’re allowing the user to see the fully rendered page before the JavaScript files start to download. You could also defer the download of external JavaScript files until the page has loaded:

<script src="https://server.com/library.js" defer></script>

If you want to find out more about mixing JavaScript with HTML, then take a look at a JavaScript Tutorial by W3Schools.

Node.js

You don’t need a web browser to execute JavaScript code anymore. There’s a tool called Node.js that provides a runtime environment for server-side JavaScript.

A runtime environment comprises the JavaScript engine, which is the language interpreter or compiler, as well as an API for interacting with the world. There are several alternative engines that come with different web browsers:

| Web Browser | JavaScript Engine |

|---|---|

| Apple Safari | JavaScriptCore |

| Microsoft Edge | V8 |

| Microsoft IE | Chakra |

| Mozilla Firefox | SpiderMonkey |

| Google Chrome | V8 |

Each of these is implemented and maintained by its vendor. For the end user, however, there’s no noticeable difference except for the performance of individual engines. Node.js uses the same V8 engine developed by Google for its Chrome browser.

When running JavaScript inside a web browser, you typically want to be able to respond to mouse clicks, dynamically add HTML elements, or maybe get an image from the webcam. But that doesn’t make sense in a Node.js application, which runs outside of the browser.

After you’ve installed Node.js for your platform, you can execute JavaScript code just like with the Python interpreter. To start an interactive session, go to your terminal and type node:

$ node

> 2 + 2

4

This is similar to the web developer console that you saw earlier. However, as soon as you try to refer to something browser related, you’ll get an error:

> alert('hello world');

Thrown:

ReferenceError: alert is not defined

That’s because your runtime environment is missing the other component, which is the browser API. At the same time, Node.js provides a set of APIs that are useful in a back-end application, such as the file system API:

> const fs = require('fs');

> fs.existsSync('/path/to/file');

false

For safety reasons, you won’t find these APIs in the browser. Imagine allowing some random website to have control over the files on your computer!

If the standard library doesn’t satisfy your needs, then you can always install a third-party package with the Node Package Manager (npm) that comes with the Node.js environment. To browse or search for packages, go to the npm public registry, which is like the Python Package Index (PyPI).

Similar to the python command, you can run scripts with Node.js:

$ echo "console.log('hello world');" > hello.js

$ node hello.js

hello world

By providing a path to a text file with the JavaScript code inside, you’re instructing Node.js to run that file instead of starting a new interactive session.

On Unix-like systems, you can even indicate which program to run the file with using a shebang comment in the very first line of the file:

#!/usr/bin/env node

console.log('hello world');

The comment has to be a path to the Node.js executable. However, to avoid hard-coding an absolute path, which may differ across installations, it’s best to let the env tool figure out where Node.js is installed on your machine.

Then you have to make the file executable before you can run it as if it were a Python script:

$ chmod +x hello.js

$ ./hello.js

hello world

The road to building full-blown web applications with Node.js is long and winding, but so is the path to writing Django or Flask applications in Python.

Foreign Language

Sometimes the runtime environment for JavaScript can be another programming language. This is typical of scripting languages in general. Python, for example, is widely used in plugin development. You’ll find it in the Sublime Text editor, GIMP, and Blender.

To give you an example, you can evaluate JavaScript code in a Java program using the scripting API:

package org.example;

import javax.script.ScriptEngine;

import javax.script.ScriptEngineManager;

import javax.script.ScriptException;

public class App {

public static void main(String[] args) throws ScriptException {

final ScriptEngineManager manager = new ScriptEngineManager();

final ScriptEngine engine = manager.getEngineByName("javascript");

System.out.println(engine.eval("2 + 2"));

}

}

This is a Java extension, though it might not be available in your particular Java virtual machine. Subsequent Java generations bundle alternative scripting engines, such as Rhino, Nashorn, and GraalVM.

Why is this useful?

As long as the performance isn’t too bad, you could reuse the code of an existing JavaScript library instead of rewriting it in another language. Perhaps solving a problem, such as math expression evaluation, would be more convenient with JavaScript than your native language. Finally, using a scripting language for behavior customization at runtime, like data filtering or validation, could be the only way to go in a compiled language.

JavaScript vs Python

In this section, you’ll compare Python vs JavaScript from a Pythonista’s perspective. There will be some new concepts ahead, but you’ll also discover a few similarities between the two languages.

Use Cases

Python is a general-purpose, multi-paradigm, high-level, cross-platform, interpreted programming language with a rich standard library and an approachable syntax.

As such, it’s used across a wide range of disciplines, including computer science education, scripting and automation, prototyping, software testing, web development, programming embedded devices, and scientific computing. Although it’s doable, you probably wouldn’t choose Python as the primary technology for video game or mobile app development.

JavaScript, on the other hand, originated solely as a client-side scripting language for making HTML documents a little more interactive. It’s intentionally simple and has a singular focus: adding behavior to user interfaces. This is still true today despite its improved capabilities. With Javascript, you can build not only web applications but also desktop programs and mobile apps. Tailor-made runtime environments let you execute JavaScript on the server or even on IoT devices.

Philosophy

Python emphasizes code readability and maintainability at the price of its expressiveness. After all, you can’t even format your code too much without breaking it. You also won’t find esoteric operators like you would in C++ or Perl since most of the Python operators are English words. Some people joke that Python is executable pseudocode thanks to its straightforward syntax.

As you’ll find out later, JavaScript offers much more flexibility but also more ways to cause trouble. For example, there’s no one right way of creating custom data types in JavaScript. Besides, the language needs to remain backward compatible with older browsers even when new syntax fixes a problem.

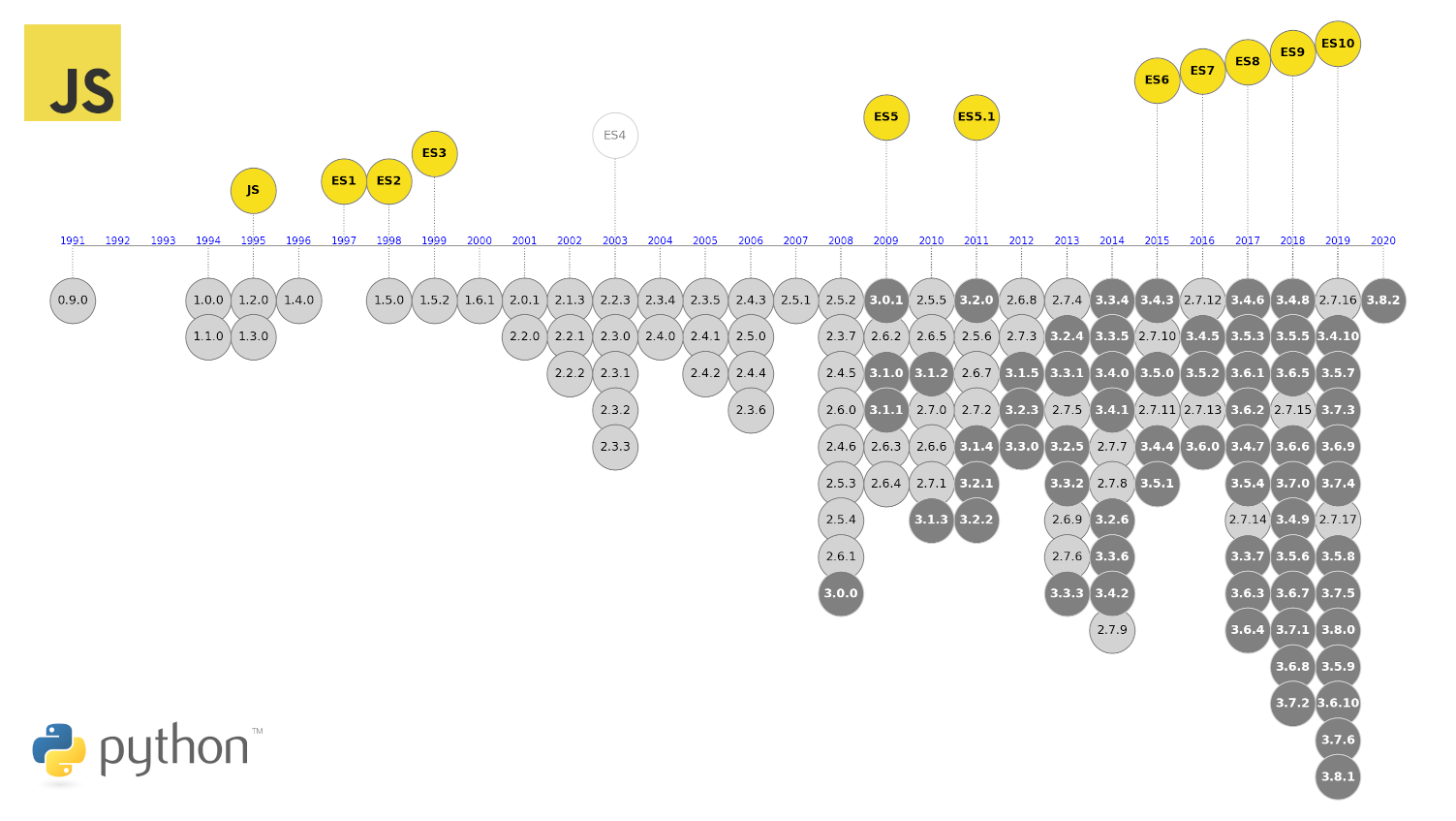

Versions

Up until recently, you would find two largely incompatible versions of Python available for download on its official website. This divide between Python 2.7 and Python 3.x was confusing to beginners and was a major factor in slowing down the adoption of the latest development branch.

In January 2020, after years of delaying the deadline, the support for Python 2.7 was finally dropped. However, despite the looming lack of security updates and warnings issued by some government agencies, there are still a lot of projects that haven’t migrated yet:

Brendan Eich created JavaScript in 1995, but the ECMAScript we know today was standardized two years later. Since then, there have been only a handful of releases, which looks stagnant compared to the multiple new versions of Python released each year during the same period.

Notice the gap between ES3 and ES5, which lasted an entire decade! Due to political conflicts and disagreements in the technical committee, ES4 never made its way to web browsers, but it was used by Macromedia (later Adobe) as a base for ActionScript.

The first major overhaul to JavaScript came in 2015 with the introduction of ES6, also known as ES2015 or ECMAScript Harmony. It brought a lot of new syntactical constructs, which made the language more mature, safe, and convenient for the programmer. It also marked a turning point in the ECMAScript release schedule, which now promises a new version every year.

Such a fast pace means that you can’t assume the latest language version has been adopted by all major web browsers since it takes time to roll out updates. That’s why transpiling and polyfills prevail. Today, pretty much any modern web browser can support ES5, which is the default target for the transpilers.

Runtime

To run a Python program, you first need to download, install, and possibly configure its interpreter for your platform. Some operating systems provide an interpreter out of the box, but it may not be the version that you’re looking to use. There are alternative Python implementations, including CPython, PyPy, Jython, IronPython, or Stackless Python. You can also choose from multiple Python distributions, such as Anaconda, that come with preinstalled third-party packages.

JavaScript is different. There’s no stand-alone program to download. Instead, every major web browser ships with some kind of JavaScript engine and an API, which together make the runtime environment. In the previous section, you learned about Node.js, which allows for running JavaScript code outside of the browser. You also know about the possibility to embed JavaScript in other programming languages.

Ecosystem

A language ecosystem consists of its runtime environment, frameworks, libraries, tools, and dialects as well as its best practices and unwritten rules. Which combination you choose will depend on your particular use case.

In the old days, you didn’t need much more than a good code editor to write JavaScript. You’d download a few libraries like jQuery, Underscore.js, or Backbone.js, or rely on a Content Delivery Network (CDN) to provide them for your clients. Today, the number of questions you need to answer and the tools you need to acquire to start building even the simplest website can be daunting.

The build process for a front-end app is as complicated as it is for a back-end app, if not more so. Your web project goes through linting, transpilation, polyfilling, bundling, minification, and more. Heck, even the CSS style sheets are no longer sufficient and need to be compiled from an extension language by a preprocessor such as Sass or Less.

To alleviate that, some frameworks offer utilities that set up the default project structure, generate configuration files, and download dependencies for you. As an example, you can create a new React app with this short command, provided that you already have the latest Node.js on your computer:

$ npx create-react-app todo

At the time of writing, this command took several minutes to finish and installed a whopping 166 MB in 1,815 packages! Compare this to starting a Django project in Python, which is instantaneous:

$ django-admin startproject blog

The modern JavaScript ecosystem is enormous and keeps evolving, which makes it impossible to give a thorough overview of its elements. You’ll encounter plenty of foreign tools as you’re learning JavaScript. However, the concepts behind some of them will sound familiar. Here’s how you can map them back to Python:

| Python | JavaScript | |

|---|---|---|

| Code Editor / IDE | PyCharm, VS Code | Atom, VS Code, WebStorm |

| Code Formatter | black |

Prettier |

| Dependency Manager | Pipenv, poetry |

bower (deprecated), npm, yarn |

| Documentation Tool | Sphinx |

JSDoc, sphinx-js |

| Interpreter | bpython, ipython, python |

node |

| Library | requests, dateutil |

axios, moment |

| Linter | flake8, pyflakes, pylint |

eslint, tslint |

| Package Manager | pip, twine |

bower (deprecated), npm, yarn |

| Package Registry | PyPI | npm |

| Package Runner | pipx |

npx |

| Runtime Manager | pyenv |

nvm |

| Scaffolding Tool | cookiecutter |

cookiecutter, Yeoman |

| Test Framework | doctest, nose, pytest |

Jasmine, Jest, Mocha |

| Web Framework | Django, Flask, Tornado | Angular, React, Vue.js |

This list isn’t exhaustive. Besides, some of the tools mentioned above have overlapping capabilities, so it’s hard to make an apples-to-apples comparison in each category.

Sometimes there isn’t a direct analogy between Python vs JavaScript. For example, while you may be used to creating isolated virtual environments for your Python projects, Node.js handles that out of the box by installing dependencies into a local folder.

Conversely, JavaScript projects may require additional tools that are unique to front-end development. One such tool is Babel, which transpiles your code according to various plugins grouped into presets. It can handle experimental ECMAScript features as well as TypeScript and even React’s JSX extension syntax.

Another category of tool is the module bundler, whose role is to consolidate multiple independent source files into one that can be easily consumed by a web browser.

During development, you want to break down your code into reusable, testable, and self-contained modules. That’s reasonable for an experienced Python programmer. Unfortunately, JavaScript didn’t originally come with support for modularity. You still need to use a separate tool for that, although this requirement is changing. Popular choices for module bundlers are webpack, Parcel, and Browserify, which can also handle static assets.

Then you have build automation tools such as Grunt and gulp. They are vaguely similar to Fabric and Ansible in Python, although they’re used locally. These tools automate boring tasks such as copying files or running the transpiler.

In a large-scale single-page application (SPA) with a lot of interactive UI elements, you may need a specialized library such as Redux or MobX for state management. These libraries aren’t tied to any particular front-end framework but can be quickly hooked up.

As you can see, learning the JavaScript ecosystem is an endless journey.

Memory Model

Both languages take advantage of automatic heap memory management to eliminate human error and to reduce cognitive load. Nevertheless, this doesn’t completely free you from the risk of getting a memory leak, and it adds some performance overhead.

Note: A memory leak occurs when a piece of memory that is no longer needed remains unnecessarily occupied and there is no way to deallocate it since it’s no longer reachable from your code. A common source of memory leaks in JavaScript are global variables and closures that hold strong references to defunct objects.

The orthodox CPython implementation uses reference counting as well as non-deterministic garbage collection (GC) to deal with reference cycles. Occasionally, you may be forced to manually allocate and reclaim the memory when you venture into writing a custom C extension module.

In JavaScript, the actual implementation of memory management is also left to your particular engine and version since it’s not a part of the language specification. The basic strategy for garbage collection is usually the mark-and-sweep algorithm, but various optimization techniques exist.

For example, the heap can be organized into generations that separate short-lived objects from long-lived ones. Garbage collection can run concurrently to offload the main thread of execution. Taking an incremental approach can help avoid bringing the program to a complete stop while the memory is cleaned up.

JavaScript Type System

You must be itching to learn about the JavaScript syntax, but first let’s take a quick look at its type system. It’s one of the most important components that define any programming language.

Type Checking

Both Python and JavaScript are dynamically typed because they check types at runtime, when the application is executing, rather than at compile time. It’s convenient because you aren’t forced to declare a variable’s type such as int or str:

>>> data = 42

>>> data = 'This is a string'

Here, you reuse the same variable name for two different kinds of entities that have distinct representations in computer memory. First it’s an integer number, and then it’s a piece of text.

Note: It’s worth noting that some statically typed languages, such as Scala, also don’t require an explicit type declaration as long as it can be inferred from the context.

Dynamic typing is often misunderstood as not having any types whatsoever. This is coming from languages in which a variable works like a box that can only fit a certain type of object. In both Python and JavaScript, the type information is tied not to the variable but to the object it points to. Such a variable is merely an alias, a label, or a pointer to some object in memory.

A lack of type declarations is great for prototyping, but in larger projects it quickly becomes a bottleneck from the maintenance point of view. Dynamic typing is less secure due to a higher risk of bugs going undetected inside of infrequently exercised code execution paths.

Moreover, it makes reasoning about the code much more difficult both for humans and for code editors. Python addressed this problem by introducing type hinting, which you can sprinkle variables with:

data: str = 'This is a string'

By default, type hints provide only informative value since the Python interpreter doesn’t care about them at runtime. However, you can add a separate utility, such as a static type checker, to your tool chain to get an early warning about mismatched types. The type hints are completely optional, which makes it possible to combine dynamically typed code with statically typed code. This approach is known as gradual typing.

The idea of gradual typing was borrowed from TypeScript, which is essentially JavaScript with types that you can transpile back to plain old JavaScript.

Another common feature of both languages is the use of duck typing for testing type compatibility. However, an area where Python vs JavaScript are significantly different is the strength of their type-checking mechanisms.

Python demonstrates strong typing by refusing to act upon objects with incompatible types. For example, you can use the plus (+) operator to add numbers or to concatenate strings, but you can’t mix the two:

>>> '3' + 2

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

The interpreter won’t implicitly promote one type to another. You have to decide for yourself and make a suitable type casting manually. If you wanted an algebraic sum, then you’d do this:

>>> int('3') + 2

5

To join the two strings together, you’d cast the second operand accordingly:

>>> '3' + str(2)

>>> '32'

JavaScript, on the other hand, uses weak typing, which automatically coerces types according to a set of rules. Unfortunately, these rules are inconsistent and hard to remember as they depend on operator precedence.

Taking the same example as before, JavaScript will implicitly convert numbers to strings when you use the plus (+) operator:

> '3' + 2

'32'

That’s great as long as it’s the desired behavior. Otherwise, you’ll be pulling your hair out trying to find the root cause of a logical error. But it gets even more funky than that. Let’s see what happens if you change the operator to something else:

> '3' - 2

1

Now it’s the other operand that gets converted to a number so the end result isn’t a string. As you can see, weak typing can be quite surprising.

The strength of type checking isn’t just black and white. Python lies somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. For instance, it’ll happily add an integer to a floating-point number, whereas the Swift programming language would raise an error in such a situation.

Note: Strong vs weak typing is independent from static vs dynamic typing. For instance, the C programming language is statically and weakly typed at the same time.

To recap, JavaScript is dynamically as well as weakly typed and supports duck typing.

JavaScript Types

In Python, everything is an object, whereas JavaScript makes a distinction between primitive and reference types. They differ in a couple of ways.

First, there are only a few predefined primitive types that you need to care about because you can’t make your own. The majority of built-in data types that come with JavaScript are reference types.

These are the only primitive types available in JavaScript:

booleannullnumberstringsymbol(since ES6)undefined

On the other hand, here are a handful of reference types that come with JavaScript off the shelf:

ArrayBooleanDateMapNumberObjectRegExpSetStringSymbol- (…)

There’s also a proposal to include a new BigInt numeric type, which some browsers already support, in ES11. Other than that, any custom data types that you might define are going to be reference types.

Variables of primitive types are stored in a special memory area called the stack, which is fast but has a limited size and is short-lived. Conversely, objects with reference types are allocated on the heap, which is only restricted by the amount of physical memory available on your computer. Such objects have a much longer life cycle but are slightly slower to access.

Primitive types are bare values without any attributes or methods to call. However, as soon as you try to access one using dot notation, the JavaScript engine will instantly wrap a primitive value in the corresponding wrapper object:

> 'Lorem ipsum'.length

11

Even though a string literal in JavaScript is a primitive data type, you can check its .length attribute. What happens under the hood is that your code is replaced with a call to the String object’s constructor:

> new String('Lorem ipsum').length

11

A constructor is a special function that creates a new instance of a given type. You can see that the .length attribute is defined by the String object. This wrapping mechanism is known as autoboxing and was copied directly from the Java programming language.

The other and more tangible difference between primitive and reference types is how they’re passed around. Specifically, whenever you assign or pass a value of a primitive type, you actually create a copy of that value in memory. Here’s an example:

> x = 42

> y = x

> x++ // This is short for x += 1

> console.log(x, y)

43 42

The assignment y = x creates a new value in memory. Now you have two distinct copies of the number 42 referenced by x and y, so incrementing one doesn’t affect the other.

However, when you pass a reference to an object literal, then both variables point to the same entity in memory:

> x = {name: 'Person1'}

> y = x

> x.name = 'Person2'

> console.log(y)

{name: 'Person2'}

Object is a reference type in JavaScript. Here, you’ve got two variables, x and y, referring to the same instance of a Person object. The change made to one of the variables is reflected in the other variable.

Last but not least, primitive types are immutable, which means that you can’t change their state once they are initialized. Every modification, such as incrementing a number or making text uppercase, results in a brand-new copy of the original value. While this is a bit wasteful, there are plenty of good reasons to use immutable values, including thread safety, simpler design, and consistent state management.

Note: To be fair, this is almost identical to how Python deals with passing objects despite its lack of primitive types. Mutable types such as list and dict don’t create copies, whereas immutable types such as int and str do.

To check if a variable is a primitive type or a reference type in JavaScript, you can use the built-in typeof operator:

> typeof 'Lorem ipsum'

'string'

> typeof new String('Lorem ipsum')

'object'

For reference types, the typeof operator always returns a generic "object" string.

Note: Always use the typeof operator to check if a variable is undefined. Otherwise, you may find yourself in trouble:

> typeof noSuchVariable === 'undefined'

true

> noSuchVariable === undefined

ReferenceError: noSuchVariable is not defined

Comparing a non-existing variable to any value will throw an exception!

If you want to obtain a more detailed information about a particular type, then you have a couple of options:

> today = new Date()

> today.constructor.name

'Date'

> today instanceof Date

true

> Date.prototype.isPrototypeOf(today)

true

You can try checking an object’s constructor name using the instanceof operator, or you can test if it’s derived from a particular parent type with the .prototype property.

Type Hierarchy

Python and JavaScript are object-oriented programming languages. They both allow you to express code in terms of objects that encapsulate identity, state, and behavior. While most programming languages, including Python, use class-based inheritance, JavaScript is one of a few that don’t.

Note: A class is a template for objects. You can think of classes like cookie cutters or object factories.

To create hierarchies of custom types in JavaScript, you need to become familiar with prototypal inheritance. That is often one the most challenging concepts to understand when you make a switch from a more classical inheritance model. If you have twenty minutes, then you can watch a great video on prototypes that clearly explains the concept.

Note: Contrary to Python, multiple inheritance isn’t possible in JavaScript because any given object can have only one prototype. That said, you can use proxy objects, which were introduced in ES6, to mitigate that.

The gist of the story is that there are no classes in JavaScript. Well, technically, you can use the class keyword that was introduced in ES6, but it’s purely a syntactic sugar to make things easier for newcomers. Prototypes are still used behind the scenes, so it’s worthwhile to get a closer look at them, which you’ll have a chance to do later on.

Function Type

Lastly, functions are an interesting part of the JavaScript and Python type systems. In both languages, they’re often referred to as first-class citizens or first-class objects because the interpreter doesn’t treat them any differently than other data types. You can pass a function as an argument, return it from another function, or store it in a variable just like a regular value.

This is a very powerful feature that allows you to define higher-order functions and to take full advantage of the functional paradigm. For languages in which functions are special entities, you can work around this with the help of design patterns such as the strategy pattern.

JavaScript is even more flexible than Python in regard to functions. You can define an anonymous function expression full of statements with side effects, whereas Python’s lambda function must contain exactly one expression and no statements:

let countdown = 5;

const id = setInterval(function() {

if (countdown > 0) {

console.log(`${countdown--}...`);

} else if (countdown === 0) {

console.log('Go!');

clearInterval(id);

}

}, 1000);

The built-in setInterval() lets you execute a given function periodically in time intervals expressed in milliseconds until you call clearInterval() with the corresponding ID. Notice the use of a conditional statement and the mutation of a variable from the outer scope of the function expression.

JavaScript Syntax

JavaScript and Python are both high-level scripting languages that share a fair bit of syntactical similarities. This is especially true of their latest versions. That said, JavaScript was designed to resemble Java, whereas Python was modeled after the ABC and Modula-3 languages.

Code Blocks

One of the hallmarks of Python is the use of mandatory indentation to denote a block of code, which is quite unusual and frowned upon by new Python converts. Many popular programming languages, including JavaScript, use curly brackets or special keywords instead:

function fib(n)

{

if (n > 1) {

return fib(n-2) + fib(n-1);

}

return 1;

}

In JavaScript, every block of code consisting of more than one line needs an opening { and a closing }, which gives you the freedom to format your code however you like. You can mix tabs with spaces and don’t need to pay attention to your bracket placement.

Unfortunately, this can result in messy code and sectarian conflicts between developers with different style preferences. This makes code reviews problematic. Therefore, you should always establish coding standards for your team and use them consistently, preferably in an automated way.

Note: You could simplify the function body above by taking advantage of the ternary if (?:), which is sometimes called the Elvis operator because it looks like the hairstyle of the famous singer:

return (n > 1) ? fib(n-2) + fib(n-1) : 1;

This is equivalent to a conditional expression in Python.

Speaking of indentation, it’s customary for JavaScript code to be formatted using two spaces per indentation level instead of the recommended four in Python.

Statements

To reduce friction for those making a switch from Java or another C-family programming language, JavaScript terminates statements with a familiar semicolon (;). If you’ve ever programmed in one of those languages, then you’ll know that putting a semicolon after an instruction becomes muscle memory:

alert('hello world');

Semicolons aren’t required in JavaScript, though, because the interpreter will take a guess and insert one for you automatically. In most cases, it’ll be right, but sometimes it may lead to peculiar results.

Note: You can use semicolons in Python, too! Although they’re not very popular, they help isolate multiple statements on a single line:

import pdb; pdb.set_trace()

People have strong opinions on whether to use the semicolon explicitly or not. While there are a few corner cases in which it matters, it’s largely just a convention.

Identifiers

Identifiers, such as variable or function names, must be alphanumeric in JavaScript and Python. In other words, they can only contain letters, digits, and a few special characters. At the same time, they can’t start with a digit. While non-Latin characters are allowed, you should generally avoid them:

- Legal:

foo,foo42,_foo,$foo,fößar - Illegal:

42foo

Names in both languages are case sensitive, so variables like foo and Foo are distinct. Nonetheless, the naming conventions in JavaScript are slightly different than in Python:

| Python | JavaScript | |

|---|---|---|

| Type | ProjectMember |

ProjectMember |

| Variable, Attribute, or Function | first_name |

firstName |

In general, Python recommends using lower_case_with_underscores, also known as snake_case, for compound names, so that individual words get separated with an underscore character (_). The only exception to that rule is classes, whose names should follow the CapitalizedWords, or Pascal case, style. JavaScript also uses CapitalizedWords for types but mixedCase, or lower camelCase, for everything else.

Comments

JavaScript has single-line as well as multiline comments:

x++; // This is a single-line comment

/*

This whole paragraph

is a comment and will

be ignored.

*/

You can start a comment anywhere on a line using a double slash (//), which is similar to Python’s hash sign (#). While there are no multiline comments in Python, you can simulate them by enclosing a fragment of code within a triple quote (''') to create a multiline string. Alternatively, you can wrap it in an if statement that never evaluates to True:

if False:

...

You can use this trick, for example, to temporarily disable an existing block of code during debugging.

String Literals

To define string literals in JavaScript, you can use a pair of single quotes (') or double quotes (") interchangeably, just like in Python. However, for a long time, there was no way to define multiline strings in JavaScript. Only ES6 in 2015 brought template literals, which look like a hybrid of f-strings and multiline strings borrowed from Python:

var name = 'John Doe';

var message = `Hi ${name.split(' ')[0]},

We're writing to you regarding...

Kind regards,

Xyz

`;

A template starts with a backtick (`), also known as the grave accent, instead of regular quotes. To interpolate a variable or any legal expression, you have to use the dollar sign followed by a pair of matching curly brackets: ${...}. This is different from Python’s f-strings, which don’t require the dollar sign.

Variable Scopes

When you define a variable in JavaScript the same way that you would normally do in Python, you’re implicitly creating a global variable. Since global variables break encapsulation, you should rarely need them! The correct way to declare variables in JavaScript has always been through the var keyword:

x = 42; // This is a global variable. Did you really mean that?

var y = 15; // This is global only when declared in a global context.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t declare a truly local variable, and it has its own problems that you’ll find out about in the upcoming section. Since ES6, there’s been a better way to declare variables and constants with the let and const keywords, respectively:

> let name = 'John Doe';

> const PI = 3.14;

> PI = 3.1415;

TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

Unlike constants, variables in JavaScript don’t need an initial value. You can provide one later:

let name;

name = 'John Doe';

When you leave off the initial value, you create what’s called a variable declaration rather than a variable definition. Such variables automatically receive a special value of undefined, which is one of the primitive types in JavaScript. This is different in Python, where you always define variables except for variable annotations. But even then, these variables aren’t technically declared:

name: str

name = 'John Doe'

Such an annotation doesn’t affect the variable life cycle. If you referred to name before the assignment, then you’d receive a NameError exception.

Switch Statements

If you’ve been complaining about Python not having a proper switch statement, then you’ll be happy to learn that JavaScript does:

// As with C, clauses will fall through unless you break out of them.

switch (expression) {

case 'kilo':

value = bytes / 2**10;

break;

case 'mega':

value = bytes / 2**20;

break;

case 'giga':

value = bytes / 2**30;

break;

default:

console.log(`Unknown unit: "${expression}"`);

}

The expression can evaluate to any type, including a string, which wasn’t always the case in the older Java versions that influenced JavaScript. By the way, did you notice the familiar exponentiation operator (**) in the code snippet above? It wasn’t available in JavaScript until ES7 in 2016.

Enumerations

There’s no native enumeration type in pure JavaScript, but you can use the enum type in TypeScript or emulate one with something similar to this:

const Sauce = Object.freeze({

BBQ: Symbol('bbq'),

CHILI: Symbol('chili'),

GARLIC: Symbol('garlic'),

KETCHUP: Symbol('ketchup'),

MUSTARD: Symbol('mustard')

});

Freezing an object prevents you from adding or removing its attributes. This is different from a constant, which can be mutable! A constant will always point to the same object, but the object itself might change its value:

> const fruits = ['apple', 'banana'];

> fruits.push('orange'); // ['apple', 'banana', 'orange']

> fruits = [];

TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

You can add an orange to the array, which is mutable, but you can’t modify the constant that is pointing to it.

Arrow Functions

Until ES6, you could only define a function or an anonymous function expression using the function keyword:

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

let add = function(a, b) {

return a + b;

};

However, to reduce the boilerplate code and to fix a slight problem with binding functions to objects, you can now use the arrow function in addition to the regular syntax:

let add = (a, b) => a + b;

Notice that there’s no function keyword anymore, and the return statement is implicit. The arrow symbol (=>) separates the function’s arguments from its body. People sometimes call it the fat arrow function because it was originally borrowed from CoffeeScript, which also has a thin arrow (->) counterpart.

Arrow functions are most suitable for small, anonymous expressions like lambdas in Python, but they can contain multiple statements with side effects if needed:

let add = (a, b) => {

const result = a + b;

return result;

}

When you want to return an object literal from an arrow function, you need to wrap it in parentheses to avoid ambiguity with a block of code:

let add = (a, b) => ({

result: a + b

});

Otherwise, the function body would be confused for a block of code without any return statements, and the colon would create a labeled statement rather than a key-value pair.

Default Arguments

Starting with ES6, function arguments can have default values like in Python:

> function greet(name = 'John') {

… console.log('Hello', name);

… }

> greet();

Hello John

Unlike Python, however, the default values are resolved every time the function is called instead of only when it’s defined. This makes it possible to safely use mutable types as well as to dynamically refer to other arguments passed at runtime:

> function foo(a, b=a+1, c=[]) {

… c.push(a);

… c.push(b);

… console.log(c);

… }

> foo(1);

[1, 2]

> foo(5);

[5, 6]

Every time you call foo(), its default arguments are derived from the actual values passed to the function.

Variadic Functions

When you want to declare a function with variable number of parameters in Python, you take advantage of the special *args syntax. The JavaScript equivalent would be the rest parameter defined with the spread (...) operator:

> function average(...numbers) {

… if (numbers.length > 0) {

… const sum = numbers.reduce((a, x) => a + x);

… return sum / numbers.length;

… }

… return 0;

… }

> average();

0

> average(1);

1

> average(1, 2);

1.5

> average(1, 2, 3);

2

The spread operator can also be used to combine iterable sequences. For example, you can extract the elements of one array into another:

const redFruits = ['apple', 'cherry'];

const fruits = ['banana', ...redFruits];

Depending on where you place the spread operator in the target list, you may prepend or append elements or insert them somewhere in the middle.

Destructuring Assignments

To unpack an iterable into individual variables or constants, you can use the destructuring assignment:

> const fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'orange'];

> const [a, b, c] = fruits;

> console.log(b);

banana

Similarly, you can destructure and even rename object attributes:

const person = {name: 'John Doe', age: 42, married: true};

const {name: fullName, age} = person;

console.log(`${fullName} is ${age} years old.`);

This helps avoid name collisions for variables defined within one scope.

with Statements

There’s an alternative way to drill down to an object’s attributes using the slightly old with statement:

const person = {name: 'John Doe', age: 42, married: true};

with (person) {

console.log(`${name} is ${age} years old.`);

}

It works like a construct in Object Pascal, in which a local scope gets temporarily augmented with attributes of the given object.

Note: The with statements in Python vs JavaScript are false friends. In Python, you use a with statement to manage resources through context managers.

Since this might be obscure, the with statement is generally discouraged and is even unavailable in strict mode.

Iterables, Iterators, and Generators

Since ES6, JavaScript has had the iterable and iterator protocols as well as generator functions, which look almost identical to Python’s iterables, iterators, and generators. To turn a regular function into a generator function, you need to add an asterisk (*) after the function keyword:

function* makeGenerator() {}

You can’t make generator functions out of arrow functions, though.

When you call a generator function, it won’t execute the body of that function. Instead, it returns a suspended generator object that conforms to the iterator protocol. To advance your generator, you can call .next(), which is similar to Python’s built-in next():

> const generator = makeGenerator();

> const {value, done} = generator.next();

> console.log(value);

undefined

> console.log(done);

true

As a result, you’ll always get a status object with two attributes: the subsequent value and a flag that indicates if the generator has been exhausted. Python throws the StopIteration exception when there are no more values in the generator.

To return some value from your generator function, you can use either the yield keyword or the return keyword. The generator will keep feeding values until there are no more yield statements, or until you return prematurely:

let shouldStopImmediately = false;

function* randomNumberGenerator(maxTries=3) {

let tries = 0;

while (tries++ < maxTries) {

if (shouldStopImmediately) {

return 42; // The value is optional

}

yield Math.random();

}

}

The above generator will keep yielding random numbers until it reaches the maximum number of tries or you set a flag to make it terminate early.

The equivalent of the yield from expression in Python, which delegates the iteration to another iterator or an iterable object, is the yield* expression:

> function* makeGenerator() {

… yield 1;

… yield* [2, 3, 4];

… yield 5;

… }

> const generator = makeGenerator()

> generator.next();

{value: 1, done: false}

> generator.next();

{value: 2, done: false}

> generator.next();

{value: 3, done: false}

> generator.next();

{value: 4, done: false}

> generator.next();

{value: 5, done: false}

> generator.next();

{value: undefined, done: true}

Interestingly, it’s legal to return and yield at the same time:

function* makeGenerator() {

return yield 42;

}

However, due to a grammar limitation, you’d have to use parentheses to achieve the same effect in Python:

def make_generator():

return (yield 42)

To explain what’s going on, you can rewrite that example by introducing a helper constant:

function* makeGenerator() {

const message = yield 42;

return message;

}

If you know coroutines in Python, then you’ll remember that generator objects can be both producers and consumers. You can send arbitrary values into a suspended generator by providing an optional argument to .next():

> function* makeGenerator() {

… const message = yield 'ping';

… return message;

… }

> const generator = makeGenerator();

> generator.next();

{value: "ping", done: false}

> generator.next('pong');

{value: "pong", done: true}

The first call to .next() runs the generator until the first yield expression, which happens to return "ping". The second call passes a "pong" that is stored in the constant and immediately returned from the generator.

Asynchronous Functions

The nifty mechanism explored above was the basis for asynchronous programming and the adoption of the async and await keywords in Python. JavaScript followed the same path by bringing in asynchronous functions with ES8 in 2017.

While a generator function returns a special kind of iterator, the generator object, asynchronous functions always return a promise, which was first introduced in ES6. A promise represents the future result of an asynchronous call such as fetch() from the Fetch API.

When you return any value from an asynchronous function, it’s automatically wrapped in a promise object that can be awaited in another asynchronous function:

async function greet(name) {

return `Hello ${name}`;

}

async function main() {

const promise = greet('John');

const greeting = await promise;

console.log(greeting); // "Hello John"

}

main();

Typically, you’d await and assign the result in one go:

const greeting = await greet('John');

Although you can’t completely get rid of promises with asynchronous functions, they significantly improve your code readability. It starts to look like synchronous code even though your functions can be paused and resumed multiple times.

One notable difference from the asynchronous code in Python is that, in JavaScript, you don’t need to manually set up the event loop, which runs in the background implicitly. JavaScript is inherently asynchronous.

Objects and Constructors

You know from an earlier part of this article that JavaScript doesn’t have a concept of classes. Instead, it knows about objects. You can create new objects using object literals, which look like Python dictionaries:

let person = {

name: 'John Doe',

age: 42,

married: true

};

It behaves like a dictionary in that you can access individual attributes using dot syntax or square brackets:

> person.age++;

> person['age'];

43

Object attributes don’t need to be enclosed in quotes unless they contain spaces, but that isn’t a common practice:

> let person = {

… 'full name': 'John Doe'

… };

> person['full name'];

'John Doe'

> person.full name;

SyntaxError: Unexpected identifier

Just like a dictionary and some objects in Python, objects in JavaScript have dynamic attributes. That means you can add new attributes or delete existing ones from an object:

> let person = {name: 'John Doe'};

> person.age = 42;

> console.log(person);

{name: "John Doe", age: 42}

> delete person.name;

true

> console.log(person);

{age: 42}

Starting from ES6, objects can have attributes with computed names:

> let person = {

… ['full' + 'Name']: 'John Doe'

… };

> person.fullName;

'John Doe'

Python dictionaries and JavaScript objects are allowed to contain functions as their keys and attributes. There are ways to bind such functions to their owner so that they behave like class methods. For example, you can use a circular reference:

> let person = {

… name: 'John Doe',

… sayHi: function() {

… console.log(`Hi, my name is ${person.name}.`);

… }

… };

> person.sayHi();

Hi, my name is John Doe.

sayHi() is tightly coupled to the object it belongs to because it refers to the person variable by name. If you were to rename that variable at some point, then you’d have to go through the whole object and make sure to update all occurrences of that variable name.

A slightly better approach takes advantage of the implicit this variable that is exposed to functions. The value of this can be different depending on who’s calling the function:

> let jdoe = {

… name: 'John Doe',

… sayHi: function() {

… console.log(`Hi, my name is ${this.name}.`);

… }

… };

> jdoe.sayHi();

Hi, my name is John Doe.

After replacing a hard-coded person with this, which is similar to Python’s self, it won’t matter what the variable name is, and the result will be the same as before.

Note: The example above won’t work if you replace the function expression with an arrow function, because the latter has different scoping rules for the this variable.

That’s great, but as soon as you decide to introduce more objects of the same Person kind, you’ll have to repeat all attributes and redefine all functions in each object. What you’d rather have is a template for Person objects.

The canonical way of creating custom data types in JavaScript is to define a constructor, which is an ordinary function:

function Person() {

console.log('Calling the constructor');

}

As a convention, to denote that such a function has a special meaning, you’d capitalize the first letter to follow CapitalizedWords instead of the usual mixedCase.

On the syntactical level, however, it’s just a function that you can call normally:

> Person();

Calling the constructor

undefined

What makes it special is how you call it:

> new Person();

Calling the constructor

Person {}

When you add the new keyword in front of the function call, it’ll implicitly return a brand-new instance of a JavaScript object. That means your constructor shouldn’t contain the return statement.

While the interpreter is responsible for allocating memory for and scaffolding a new object, the role of a constructor is to give the object an initial state. You can use the previously mentioned this keyword to refer to a new instance under construction:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

this.sayHi = function() {

console.log(`Hi, my name is ${this.name}.`);

}

}

Now you can create multiple distinct Person entities:

const jdoe = new Person('John Doe');

const jsmith = new Person('John Smith');

Alright, but you’re still duplicating function definitions across all instances of the Person type. The constructor is just a factory that hooks the same values to individual objects. It’s wasteful and could lead to inconsistent behavior if you were to change it at some point. Consider this:

> const jdoe = new Person('John Doe');

> const jsmith = new Person('John Smith');

> jsmith.sayHi = _ => console.log('What?');

> jdoe.sayHi();

Hi, my name is John Doe.

> jsmith.sayHi();

What?

Since every object gets a copy of its attributes, including functions, you must carefully update all instances to keep a uniform behavior. Otherwise, they’ll do different things, which typically isn’t what you want. Objects might have a different state, but their behavior usually won’t change.

Prototypes

As a rule of thumb, you should move the business logic from the constructor, which is concerned about data, to the prototype object:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

Person.prototype.sayHi = function() {

console.log(`Hi, my name is ${this.name}.`);

};

Every object has a prototype. You can access your custom data type’s prototype by referring to the .prototype attribute of your constructor. It’ll already have a few predefined attributes, such as .toString(), that are common to all objects in JavaScript. You can add more attributes with your custom methods and values.

When JavaScript is looking for an object’s attribute, it begins by trying to find it in that object. Upon failure, it moves on to the respective prototype. Therefore, attributes defined in a prototype are shared across all instances of the corresponding type.

Prototypes are chained, so the attribute lookup continues until there are no more prototypes in the chain. This is analogous to type hierarchy through inheritance.

Not only can you create methods in one place thanks to the prototypes, but you can also create static attributes by attaching them to one:

> Person.prototype.PI = 3.14;

> new Person('John Doe').PI;

3.14

> new Person('John Smith').PI;

3.14

To illustrate the power of prototypes, you may try to extend the behavior of existing objects, or even a built-in data type. Let’s add a new method to the string type in JavaScript by specifying it in the prototype object:

String.prototype.toSnakeCase = function() {

return this.replace(/\s+/g, '')

.split(/(?<=[a-z])(?=[A-Z])/g)

.map(x => x.toLowerCase())

.join('_');

};

It uses regular expressions to transform the text into snake_case. Suddenly, string variables, constants, and even string literals can benefit from it:

> "loremIpsumDolorSit".toSnakeCase();

'lorem_ipsum_dolor_sit'

However, this is a double-edged sword. In a similar way, someone could override one of the existing methods in a prototype of a popular type, which would break the assumptions made elsewhere. Such monkey patching can be useful in testing but is otherwise very dangerous.

Classes

Since ES6, there’s been an alternative way to define prototypes that uses a much more familiar syntax:

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

sayHi() {

console.log(`Hi, my name is ${this.name}.`);

}

}

Even though this looks like you’re defining a class, it’s only a convenient high-level metaphor for specifying custom data types in JavaScript. Behind the scenes, there are no real classes! For that reason, some people go so far as to advocate against using this new syntax at all.

You can have getters and setters in your class, which are similar to the Python’s class properties:

> class Square {

… constructor(size) {

… this.size = size; // Triggers the setter

… }

… set size(value) {

… this._size = value; // Sets the private field

… }

… get area() {

… return this._size**2;

… }

… }

> const box = new Square(3);

> console.log(box.area);

9

> box.size = 5;

> console.log(box.area);

25

When you omit the setter, you create a read-only property. That’s misleading, however, because you can still access the underlying private field like you can in Python.

A common pattern to encapsulate internal implementation in JavaScript is an Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE), which can look like this:

> const odometer = (function(initial) {

… let mileage = initial;

… return {

… get: function() { return mileage; },

… put: function(miles) { mileage += miles; }

… };

… })(33000);

> odometer.put(65);

> odometer.put(12);

> odometer.get();

33077

In other words, it’s an anonymous function that calls itself. You can use the newer arrow function to create an IIFE too:

const odometer = ((initial) => {

let mileage = initial;

return {

get: _ => mileage,

put: (miles) => mileage += miles

};

})(33000);

This is how JavaScript historically emulated modules to avoid name collisions in the global namespace. Without an IIFE, which uses closures and function scope to expose only a limited public-facing API, everything would be accessible from the calling code.

Sometimes you want to define a factory or a utility function that logically belongs to your class. In Python, you have the @classmethod and @staticmethod decorators, which allow you to associate static methods with the class. To achieve the same result in JavaScript, you need to use the static method modifier:

class Color {

static brown() {

return new Color(244, 164, 96);

}

static mix(color1, color2) {

return new Color(...color1.channels.map(

(x, i) => (x + color2.channels[i]) / 2

));

}

constructor(r, g, b) {

this.channels = [r, g, b];

}

}

const color1 = Color.brown();

const color2 = new Color(128, 0, 128);

const blended = Color.mix(color1, color2);

Note that there’s no way of defining static class attributes at the moment, at least not without additional transpiler plugins.

Chaining prototypes can resemble class inheritance when you extend one class from another:

class Person {

constructor(firstName, lastName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

}

fullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

}

}

class Gentleman extends Person {

signature() {

return 'Mr. ' + super.fullName()

}

}

In Python, you could extend more than one class, but that it isn’t possible in JavaScript. To reference attributes from the parent class, you can use super(), which has to be called in the constructor to pass arguments up the chain.

Decorators

Decorators are yet another feature that JavaScript copied from Python. They’re still technically a proposal that is subject to change, but you can test them out using an online playground or a local transpiler. Be warned, however, that they require a bit of configuration. Depending on the chosen plugin and its options, you’ll get different syntax and behavior.

Several frameworks already use a custom syntax for decorators, which need to be transpiled into plain JavaScript. If you opt for the TC-39 proposal, then you’ll be able to decorate only classes and their members. It seems there won’t be any special syntax for function decorators in JavaScript.

JavaScript Quirks

It took ten days for Brendan Eich to create a prototype of what later became JavaScript. After it was presented to the stakeholders at a business meeting, the language was considered production ready and didn’t go through a lot of changes for many years.

Unfortunately, that made the language infamous for its oddities. Some people didn’t even regard JavaScript as a “real” programming language, which made it a victim of many jokes and memes.

Today, the language is much friendlier than it used to be. Nevertheless, it’s worth knowing what to avoid, since a lot of legacy JavaScript is still out there waiting to bite you.

Bogus Array

Python’s lists and tuples are implemented as arrays in the traditional sense, whereas JavaScript’s Array type has more in common with Python’s dictionary. What’s an array, then?

In computer science, an array is a data structure that occupies a contiguous block of memory, and whose elements are ordered and have homogeneous sizes. This way, you can access them randomly with a numerical index.

In Python, a list is an array of pointers that are typically integer numbers, which reference heterogeneous objects scattered around in various regions of memory.

Note: For low-level arrays in Python, you might be interested in checking out the built-in array module.

JavaScript’s array is an object whose attributes happen to be numbers. They’re not necessarily stored next to each other. However, they keep the right order during iteration.

When you delete an element from an array in JavaScript, you make a gap:

> const fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'orange'];

> delete fruits[1];

true

> console.log(fruits);

['apple', empty, 'orange']

> fruits[1];

undefined

The array doesn’t change its size after the removal of one of its elements:

> console.log(fruits.length);

3

Conversely, you can put a new element at a distant index even though the array is much shorter:

> fruits[10] = 'watermelon';

> console.log(fruits.length);

11

> console.log(fruits);

['apple', empty, 'orange', empty × 7, 'watermelon']

This wouldn’t work in Python.

Array Sorting

Python is clever about sorting data because it can tell the difference between element types. When you sort a list of numbers, for example, it’ll put them in ascending order by default:

>>> sorted([53, 2020, 42, 1918, 7])

[7, 42, 53, 1918, 2020]

However, if you wanted to sort a list of strings, then it would magically know how to compare the elements so that they appear in lexicographical order:

>>> sorted(['lorem', 'ipsum', 'dolor', 'sit', 'amet'])

['amet', 'dolor', 'ipsum', 'lorem', 'sit']

Things get complicated when you start to mix different types:

>>> sorted([42, 'not a number'])

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'str' and 'int'

By now, you know that Python is a strongly typed language and doesn’t like mixing types. JavaScript, on the other hand, is the opposite. It’ll eagerly convert elements of incompatible types according to some obscure rules.

You can use .sort() to do the sorting in JavaScript:

> ['lorem', 'ipsum', 'dolor', 'sit', 'amet'].sort();

['amet', 'dolor', 'ipsum', 'lorem', 'sit']

It turns out that sorting strings works as expected. Let’s see how it copes with numbers:

> [53, 2020, 42, 1918, 7].sort();

[1918, 2020, 42, 53, 7]

What happened here is that the array elements got implicitly converted to strings and were sorted lexicographically. To prevent that, you have to provide your custom sorting strategy as a function of two elements to compare, for example:

> [53, 2020, 42, 1918, 7].sort((a, b) => a - b);

[7, 42, 53, 1918, 2020]

The contract between your strategy and the sorting method is that your function should return one of three values:

- Zero when the two elements are equal

- A positive number when elements need to be swapped

- A negative number when the elements are in the right order

This is a common pattern present in other languages, and it was also the old way of sorting in Python.

Automatic Semicolon Insertion

At this point, you know that semicolons in JavaScript are optional because the interpreter will insert them automatically at the end of each instruction if you don’t do so yourself.

This can lead to surprising results under some circumstances:

function makePerson(name) {

return

({

fullName: name,

createdAt: new Date()

})

}